The Handmade Postcard in China and Native America

In early modern China and Native America, labor was cheap enough and artistic talent was ample enough to spawn unique traditions of handmade postcards between 1900 and 1940. “Handmade” because each was made by dexterous human fingers, not reproduced on printing presses as the typical postcard was during the so-called Golden Age (1898-1914) of this new medium. Each card is a one-off. Handmade cards rode a wave of imperial innovation and negotiation along the borderlines between cultures. They were enmeshed in economic entanglements between peoples, benefitting from and subverting unequal relationships. They served as gestures for and against modernity, just as mass pictorial reproduction was beginning to define human social and psychological spaces. They are odd and rich anomalies.

The picture postcard industry started in the early 1890s as an inexpensive way to exchange visual “Greetings from” messages. Transportation networks built on ships and trains moved things and people around quicker than ever before. Billions of picture postcards were being mailed around the world by 1900, thanks to new postal regulations like the Universal Postal Treaty of 1893. Printing technologies – primarily the lithographic, collotype, and halftone presses, roughly in that order between 1895 and 1910 – enabled ever cheaper mass production. Postcards were truly the Instagram of their time: interactive social objects, much like the digital posts of today. Handmade postcards – a barely acknowledged type and a fraction of the total – stand out for their distinctive ability to flow against the grain. In this essay, I try to use a few of the many such postcards assembled over the past decades in my collection to discuss similar themes and approaches in such cards across continents.

China: “Pictures made from the clip and paste of multiple stamps”

The Chinese handmade stamp postcard tradition has no real equivalent, though postcards made by hand from cut-up stamps were minor occurrences in Europe and America. In the words of one collector, these postcards are “the ultimate in postcard design... Many of them were handmade by Chinese artists, a stark difference to the vast majority of postcards made by the West. Expensive to produce then, these postcards are highly sought after today and yield highest prices in the collectors’ market.” 1

Gao Lengxiang – the secretary to Cao Kun 曹锟, (1862-1938), the military leader and fifth President of the Republic of China in 1923-1924 – is said to have been the first to use stamps to make collage postcards. The variety of cards suggests the product could also have been invented in fits and starts, by firms who saw the opportunity in reusing cancelled stamps. Gao Lengxiang may simply have been the first prominent person to be associated with the practice, perhaps fascinated by the creative opportunities afforded by “these mechanically reproduced miniature documents or receipts.” 2 Most stamps on these cards are from 1910-1920. In my own collection, the earliest firmly datable postcard is from 1923. 3

The typical Chinese stamp collage postcard 4 is the ship shown in Made in China by the Chinese Stamps [Fig. 1]. The background is hand-painted watercolor. The primary foreground object or set of objects on these cards are assembled from used stamps, selected for color and printed imagery to form a ship’s mast. This consists of the stamps of an iconic Chinese ship from the most common first set of stamps printed by the new Republic of China in 1913. The lines of a postal cancellation are dramatically extended with ink to tie the two sails to the figures of a woman and man pulling at them. The woman is Eirene, the Greek goddess of peace, cut from a single French stamp popular since the 1870s.

Fig. 1: [Chinese Boat] Made in China by the Chinese Stamps. Stamp Collage Postcard, c. 1925. Undivided back, 13.9 x 8.9 cm, Author’s Collection.

Most of these cards followed set general templates. Other boat examples have hills in the background and grass in the foreground, while keeping the focus on a single boat with a mast of similar stamps. A cottage industry was likely involved in their production, with backgrounds painted by one person, stamps cut by another, placed in piles of color by size and type by a third, and so on. Efficiencies in manufacturing would have been key, even if the cards were meant to say what this one does loudly at the bottom: “Made in China by the Chinese.”

The French word “collage” means glue, the invisible ingredient that makes the whole thing work. Glue recipes were part of vendors’ competitive arsenal; remarkably, only few stamps have peeled off or discolored a century later. Stamps are exemplary collage: bits of paper glued on paper. Makers could effortlessly mix the medium with painting and line work, as in details like the oar and flags in Figure 1. The mixture could also be more subtle, as in one postcard, Chinese Girl, where a major part of its surface is watercolor, but the designs which catch the eye are tiny strips of stamps. Their cleverness and beauty supports accounts that have Chinese artists making money with this work, despite the period after 1900 presenting very trying times for Chinese artists and painters.

Stamp collage postcards were dependent on the growing number of stamps harvested from international mail coursing through the world in the first quarter of the 20th century. Most Chinese postcards, like those of other countries around the world, were printed in Europe, especially Germany. 5 This might have given some advantage to the handmade postcard publisher. No capital nor credit was needed to start ordering them from abroad, nor photograph to print from – all ingredients, especially the stamps as fodder from around the world, could be sourced locally.

Most handmade postcards have no message or electrotype other than “Union Postale Universelle Post Card” on the back. A few, like those of “Chao-chow Drawn Work Co., Shanghai” and “Swatow Drawn Work Co., Hong Kong,” are branded. Swatow seems to have been the most common brand; the firm is described in a commercial directory as “Manufacturers & Exporters of Swatow Drawn Thread Work, Embroidered Silk Shawls, Hand-made Laces . . . Wholesale & Retail.” Although managed entirely by Chinese, Swatow Drawn Work was started by missionaries in China in the 1890s as a “philanthropical venture, to assist widows and wives of men not earning sufficient to gain a livelihood.” 6 For Swatow, postcards were probably a secondary product line among many that depended on fine motor skills for execution. 7

Indeed, there is a long tradition of paper cutting known as “jianzhi” (剪纸),a popular folk art from rural China that dates to the advent of paper almost 2000 years ago. In rural areas, the craft was practiced by women to make red objects like lanterns and other patterns for festive occasions. While a direct connection between these two forms cannot be assumed, paper cutting was foundational to the stamp collage postcard.

Women were a popular subject of handmade postcards. Beautiful Chinese women dominated the lithographic calendars that flooded the domestic market around 1910-1920, often in Western dress and daring to be visible in a new world. 8 Many of the women on these cards are apparently Japanese, meant to appeal to Japanese tourists, of whom there were many in China even before the invasions of the 1930s. Western customers might hardly have known the difference between Chinese and Japanese women. A geisha seems to be shown in one example [Fig. 2], where Swiss stamps of a Greek goddess make up the bulk of the geisha’s body. One of the few cards apparently signed by a maker, “XY,” it supports the supposition that artists could be engaged by this practice.

Fig. 2: [Japanese Woman]. XY [Signed], Stamp Collage Postcard, c. 1925. Divided back, 13.9 x 9 cm, Author’s Collection.

Some postcards of women show them on display in quiet landscapes, but they are more likely to be playing tennis, riding animals, spinning cotton, pulled in human rickshaws, swinging under a tree – doing something. This contrasts with the posed images of Chinese courtesans frozen in studios on early 20th-century photographs and printed postcards. Stamped women figures were more in line with women posing with bicycles – the socially and politically active women who “embodied the dynamism and ambivalence of the early Republican movement,” in the words of Joan Judge. 9

Did the Chinese handmade postcard have any precedents besides the tradition of paper cutting? In the book The Eight Brokens, Nancy Berliner discusses 19th-century painted collage traditions in China, based on paper tickets, rubbings from bronze vessels, poetry, or eight (a symbol of good luck) different kinds of paper fragments displayed together on a large surface. 10 “Bapo” drew attention to broken nature of the items, also known as jinhuidui, 锦灰堆,or “a pile of brocade ashes.” The form privileged “the superiority of the damaged,” 11 said to represent the “decay of Chinese civilization.” In the case of handmade postcards, the “broken” stamps are put back together into a living figure, also playing on the tension between destruction and reconstruction. 12 There was at least a conceptual relationship between the two forms.

Handmade postcard were not only made for the foreigner. They tread dual spaces and easily appealed to Chinese buyers and collectors, as they do today. Very few have English titles inked in, though they also do not typically have the distinct epigraphy like signature red artist seals expected by Chinese audiences on paper goods. They fit more than one cultural palette. I like to think these cards were also an eloquent response to Western symbols of officialdom and authority, turned into scraps and recomposed in the service of traditional Chinese art and identity, as if saying “we can do something better with this in our own way.”

Native America: Extending traditional leather crafts

While a handmade – in this case hand painted – postcard tradition also developed in early 20th-century British India, it is by turning to an even more distant tradition in Native America that we can tease out some of the common features in the response to modernity that handmade cards invoke. There may seem to be no more far-fetched comparison to be made than between China and Native America. One is among the largest and oldest civilizational areas on earth, then home to hundreds of millions of people, versus tribes scattered across the vast North American continent, reduced to about 250,000 by the 1890s – about half the population of Shanghai in 1900 – through genocide and ethnic cleansing. The story of these tribes, their resistance and adaptation to settler colonists, is very different from the colonial experience in China or India. Or is it? White Americans visited “reservations,” not port cities, in their “own” country and named other people by their skin color. This was a deeply uneasy relationship, too, with “natives as symbols both of [American] national unity and threats to that nationalism.” 13

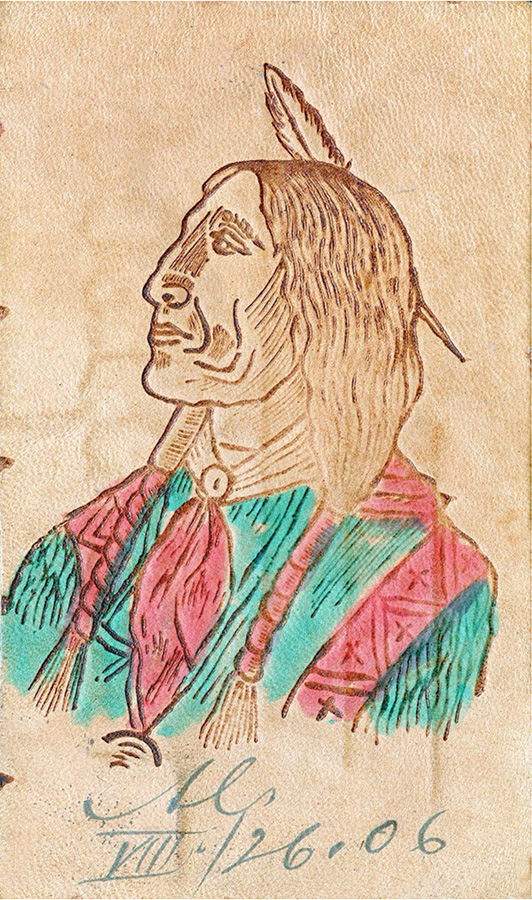

The handmade Native American postcards consisted of leather and were popular in the United States between 1903 and 1909, when they were banned by the postal service because they gummed up sorting machines. 14 Leather had a long tradition of usage among native tribes. Mostly made of deer skin, lines were incised with the heated tip of a metal tool through “pyrography,” or “writing with fire.” Iron stamp tools could also be used to create an image, so they were not always entirely incised by hand. But even then, they conveyed the sign – or visual promise – of having being made by hand through the distinctive tool dashes around the card frame, as seen on the untitled 1906 portrait of (most likely) Chief Sitting Bull [Fig. 3]. Cards were often colored in, most often with common red and green dyes. The association of leather and Native Americans was deep and even extended to “moccasin postcards,” or soft baby shoes tied together with a paper tag on which a stamp, address, and message were written, all no bigger than a regular postcard.

Fig. 3: [Chief Sitting Bull?], Leather Hand tinted Postcard, Postally used August 26, 1906. Undivided back, 13.1 x 7.7 cm, Author’s Collection.

More than any other kind of handmade postcard, the leather postcard asks to be touched. Like the stamped collage card, it references its own materiality and the native hands that presumably made it. For foreign buyers, they also marked a visit to another place. This visit could be slightly uncomfortable, if not scary, as in a popular type entitled I’m Being Well Entertained, showing a white man tied to a pole with a Native American pacing around him with a tomahawk. The native was (still) dangerous. Going to a reservation where these cards were bought represented a heroically playful act for the tourist. An undertow of violence even appears in self-reflective cards like The Indian with His Pipe of Peace . . ., featuring a native and settler’s faces with the Kiplingesque ditty: “The Indian with his Pipe of Peace Pipe/Has Slowly Passed Away/But the Irishman with/ His Piece of Pipe/Has Come Prepared/To Stay.”

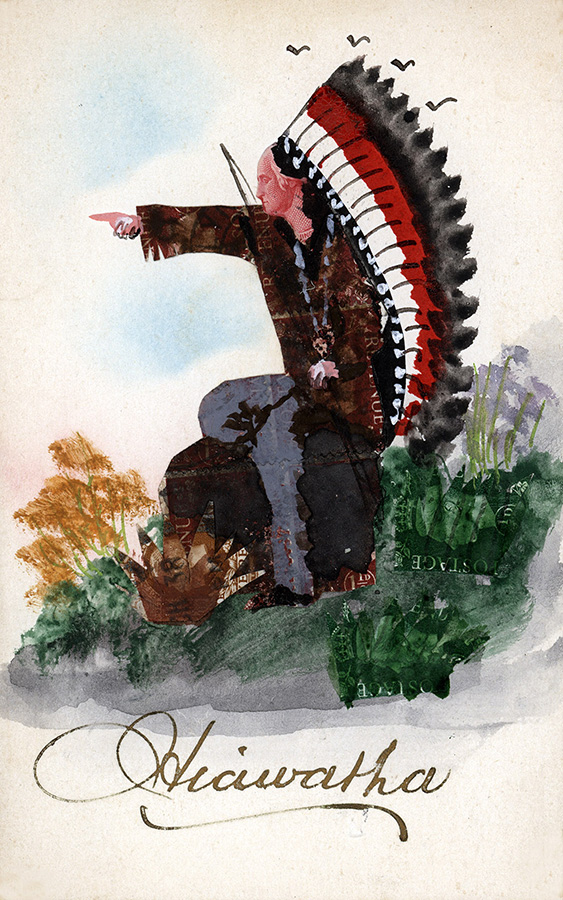

Of course, as with Indian and Chinese cards, things were not entirely one-sided. Some handmade postcards celebrated Hiawatha, the Mohawk co-founder of the Iroquois Confederacy in the mid-1100’s CE. Hiawatha himself might be a composite of many Native myths, even adapted by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow in a popular 1855 poem, Song of Hiawatha, which also resonated among settlers seeking connection to an ancient past that they were trying to possess. As Laura Goldblatt and Richard Handler put it, “representations of the US nation-state were caught between two often contradictory impulses: the need to disassociate the national culture of the United States from Europe in order to highlight the uniqueness of the American experiment, on the one hand, and the hegemonic preference for racial Anglo-Saxonism as well.” 15 A woman called Minnehaha is the lover Longfellow ascribed to Hiawatha, whose wife and daughters were killed in the struggles to unify tribes. Minnehaha was often shown together with him on handmade postcards.

The story of Pocahontas – the daughter of the Pamunkey Indian chief who had united some thirty tribes in the Virginia region – was alluded to on other handmade cards. She was said to have helped saved one of the first European colonists, who later married her for love. She apparently converted to Christianity and later died on her first visit to Europe in 1617. As the paradigmatic settler story of Indigenous acceptance of European arrival, the story of Pocahontas is full of inconsistencies: she was actually captured and held by the English for a year as ransom for prisoners held by her father, for example. Similarly, whether Minnehaha was Hiawatha’s relative, sister, or lover is unclear.

Conclusion: Modifying modernity

Handmade postcards mediated between the past and present, and between truths and the fabrication of myths, as they straddled the cultural frameworks between peoples. Perhaps more than printed postcards, in both China and Native America, they allowed for a measure of local agency in the manual dexterity and symbolism they referenced, which could be interpreted by people to their own ideological measure.

The slipperiness and hybrid nature of the handmade postcard is illustrated on one of my favorite such cards, Hiawatha [Fig. 4]. Pointing toward a future of unity, if not westward as the colonists rode, is the profile face of George Washington, the ubiquitous “Sun Yat Sen” of America’s first stamps. Other stamps used within this and another postcard of the same figure are from Germany and England, so it might have been made in America by Chinese artisans inspired by cards from home; or it could have been made by Native American artisans inspired by Chinese cards; or they could also have been made in Europe. The artisan(s) have painted over the stamps, fading select bits through the brushstrokes, an effect rare on collage cards. The card’s ambiguity is breathtaking; even as it celebrates a Native American hero in Chinese stamp format, it celebrates the hand of craftspeople and the sophistication of their perceptions of distant and local empires.

Fig. 4: Hiawatha. Stamp Collage and Painted Postcard, c. 1925. Undivided back, 13.9 x 8.8 cm, Author’s Collection.

Handmade postcards convey the tangibility of place and people, in leather or with cut stamps and watercolors. The hand added a layer of authenticity to the visual, tiny disruptions on the march to mass reproduction. Not derivatives, but intimate innovations.

Cultural borders and fault lines are deep and shallow at the same time. Deep because how Chinese and Native American artisans and publishers construed their representations was a function of long traditions, expertise, materials at hand, and the skills to work them. They relayed interactions that both invoked stereotypes and allowed something of the irreducibility of the individual to come through. The artisan burning the heads of chieftains on leather, or the woman’s fingers cutting and collaging tiny fragments of paper together, re-asserted the traditional within the modern visual experience.

Omar Khan is a graduate of Dartmouth, Columbia, and Stanford universities. He has collected vintage postcards for 30 years and is the author of Paper Jewels: Postcards from the Raj (2018). Email: omar@paperjewels.org