Green and Pleasant Paddy Fields

In the well-known lines of William Blake’s Jerusalem (c. 1804), sung often as a hymn, the poet celebrates England’s green pastures, concluding: “‘Till we have built Jerusalem / In Englands green & pleasant Land.” 1 In a similar register, the art historian WJT Mitchell noted that the category of landscape painting was a purely modern European phenomenon, encompassing a new gaze derived from an ‘originary moment’ in which the visitor gazes at ‘natural’ beauty through the lens of God. 2 Much like the evocative lyrics of Jerusalem, the act of depicting a land could never be neutral; to some extent, it always embodies one’s political, patriotic, or imperialist tendencies.

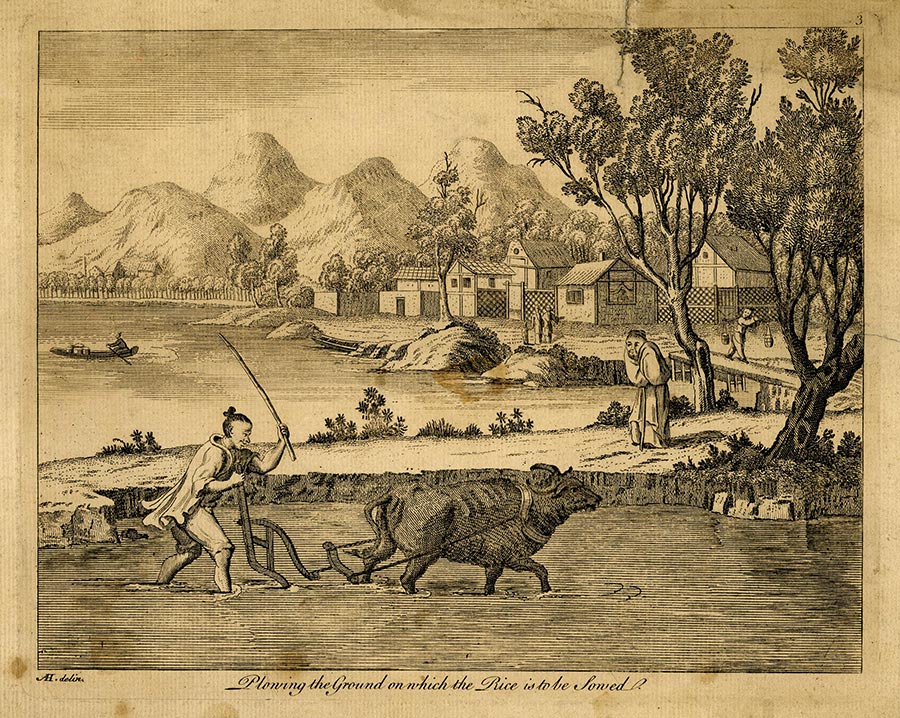

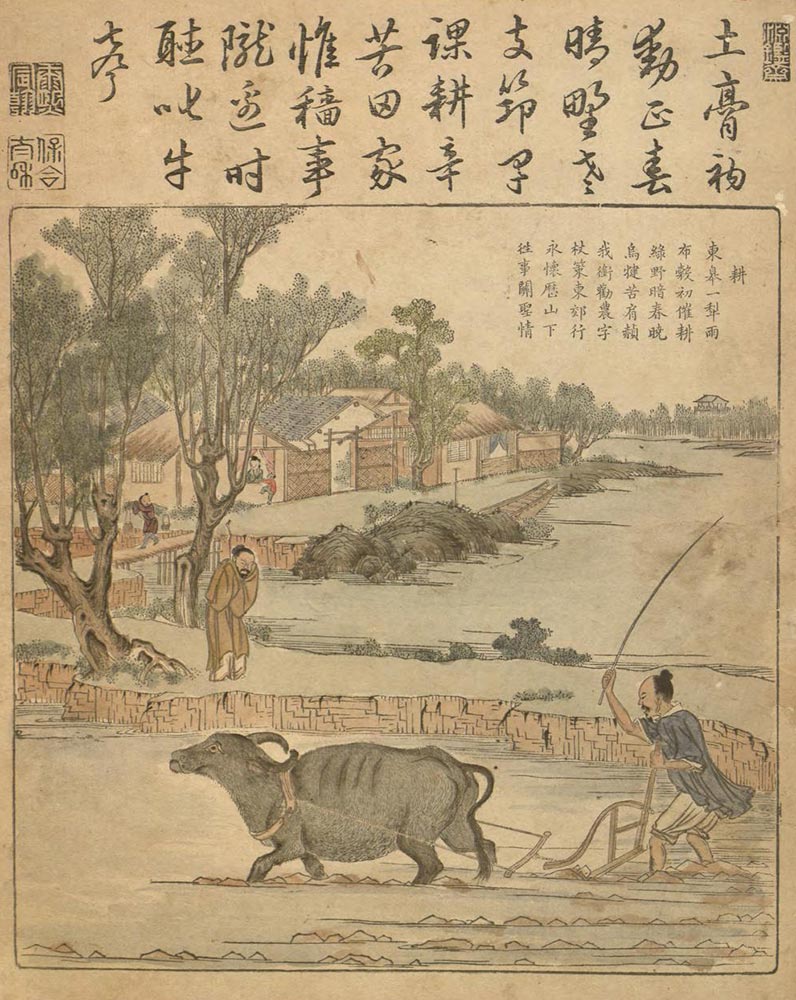

This is the first sustained study on the series of etchings originally published as The Rice Manufactury (c. 1770s) by the printmaker John June (active. 1744-1775), sold by the renowned eighteenth-century printseller John Bowles (1701?-1779) [Fig. 1]. Depicting scenes of rice cultivation in China, the etchings directly reproduce in mirror-image the Yuzhi Gengzhi tu 御製耕織圖(Imperially Commissioned Pictures of Tilling and Weaving ) (1696) [Fig. 2], an album of sets of 23 woodblock prints commissioned by the Qing Dynasty Kangxi Emperor (1654-1722, r. 1661-1722). Completed by the Qing Court astronomer Jiao Bingzhen 焦秉貞 (active c. 1680-1720), they depict two of imperial China’s most important economic activities: rice and silk production.

Fig. 1: John June (active. 1744-1775), printed by John Bowles (1701?-1779), ‘Plowing the ground on which the Rice is to be Sowed,’ The Rice Manufactury, c. 1770s, etching on paper, British Museum, London (Photo: British Museum, London) © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Notably, the historian James Hevia recognised how late 18th-century British notions of ‘China’ dovetailed with British self-identity to provide a rhetorical framework for British attitudes towards the commercial and imperial viability of China, culminating in the Macartney Embassy of 1793, which sought to open new trading opportunities. 3 By understanding how the Kangxi Emperor’s woodblock visions of rice cultivation were constructed and subsumed into a different visual repertoire in the last quarter of the 18th century through these prints in England, this essay locates these ‘novel’ landscapes within larger imperial ambitions.

Fig. 2: Jiao Bingzhen 焦秉貞 (active c. 1680-1720) , ‘Tilling (geng) 耕’, Kangxi Imperially Commissioned Pictures of Tilling and Weaving, coloured woodblock print on paper, Library of Congress, Washington, DC (Photo: Library of Congress, DC).

The British Museum online catalogue describes John June as a ‘printmaker’ who ‘etched scenes of London life.’ 4 Despite the fact that the rice cultivation prints are reproductions of Chinese woodblock prints, this identification of June as a printmaker of ‘London life’ hits surprisingly close to his reality. As the British Empire was both a geopolitical entity and a subject of the British imagination, in John June’s prints, the real subject is not China but the British imperial ‘vision’ – where scenes of ‘China’ were to be understood as a representation of nature itself, a land to be beheld and possessed.

An intercultural discourse of landscape?: Shanshui and the Western landscape

Observing the overall equilibrium in Figure 1, the viewer’s eyes are first drawn to the quiet labour of the worker in the foreground. The eye is pulled back through the receding space, to the neatly lined trees of varying species in the background, matched by an arrangement of thoughtfully composed hills. While The Rice Manufactury was known to have been in circulation by the 1770s, the prints were later republished in A New Book of Landscapes (1794). In addition to suggesting the work’s continuing popularity among the British public, the book’s title title further indicates the perceived novelty and exotic nature of the landscapes. How, then, did the Kangxi Gengzhi tu become understood as landscapes in the British prints, within a discourse that WJT Mitchell deemed to be entirely Western?

On his Second Tour to the South in 1689, Emperor Kangxi was presented with a Song Dynasty (960-1279) edition of Pictures of Tilling and Weaving, comprising original poems written by the court official Lou Shu樓壽 (1090-1162). Describing the processes of rice and silk production, these formed a highly revered tradition of sympathetic labour genre works. As the Manchu emperor of a bustling empire, Kangxi established himself through this Chinese tradition, commissioning Jiao Bingzhen to complete 23 scenes of rice production and 23 scenes of silk production as coloured woodblock prints. He also added a suite of new poems, which acknowledged the labourers’ mundane toil, thereby dignifying the role of individuals and continually encouraging the advancement of agricultural productivity.

In China, the term for landscape painting – shanshui 山水 – translates directly as ‘mountain and water.’ Deriving from a 5th-century tradition, this terminology implies the direct consideration of a highly specific subject matter, referring to natural mountains and rivers. Moreover, such paintings were historically interpreted as depicting the essential interactions between human beings and nature through metaphorical calligraphic strokes, where the focus is not on its imitative representations of reality, but rather the viewer’s contemplative experience. 5

Observing shanshui paintings such as the Xunxian shanshui tu 尋僊山水圖album of landscapes by Shitao, with their curves of recurrent rocks, trees and cone-shaped hills, the artist echoed the themes of dwelling amongst lakes and hills [Fig. 3].

Fig. 3: Shitao 石濤 (Zhu Ruoji 朱若極), Xunxian shanshui tu 尋僊山水圖 (Landscapes), c. 1690s, Album of eight leaves, ink and colour on paper, 21 × 31.4 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. (Photo: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York).

However, as Mitchell noted, all visions of scenery are ‘mediated by culture,’ and one way in which the Kangxi Gengzhi tu might match with the Western conception of landscape is the pervasive idea of the ‘artifice’ embedded in the scenes. 6 Similarly, writing about 18th-century British agricultural paintings, Christiana Payne noted how labourers who were often half-starved and exploited were visualised as attractive, optimistic, and unthreatening. 7

In Figure 1, the farmer, depicted in side-profile, appears clean and well-fed as the water buffalo pulls the plough. Lifting a whip, the man carries out his work in an atmosphere of cooperation and sensibility. The farmer is in command of the water buffalo and the ploughing activity, as an elderly man, slightly hunched over, watches from afar. Despite the activity of the foreground, a sense of stillness and timelessness is evoked in the left background, where a boat sails on the water without stirring a ripple. The labourer’s facial expressions are ambiguous. Notably, his toil is not visualised as overly gruelling, turning the focus onto nature and his surroundings – all pictured to be under his control. Sharing a similar notion of idealisation, the Kangxi Gengzhi tu offered a didactic exemplar of the social and domestic virtues of the Chinese countryside.

Functioning as Kangxi’s visions of an ideal state, the Emperor also repositions his own legacy within the Gengzhi tu. Seen in Figure 2, each picture is accompanied by two sets of texts. The first text is set in small, standard characters inside the frame of the scene, occupying the negative spaces within the view. The second texts, written in running script calligraphy above the image, are poetic reflections added by Emperor Kangxi, accompanied by his personal seals. Every single poem maintains a compassionate tone. For example, the poem on winnowing acknowledges ‘it must be understood [that to eat] white congee as it [easily] slides off a spoon, requires all kinds of effort from the farmers.’ 8 With their slender figures and oval faces, the women and men in the pictures are all elegant and healthy. Implying his watching yet sympathetic eye through the narrative voice in his poems, Kangxi expressed his commitment to a prosperous society founded upon the economic benefits of rice and silk production. Discussing how landscape was ‘integrally connected with imperialism,’ Mitchell concludes that it is within this space that ideology is ‘veiled and naturalised.’ 9 In parallel terms, despite their radically dissimilar original interpretative contexts, as the works are moved into an English discursive framework, the Gengzhi tu compositions transform from didactic images of labour into Western landscapes as The Rice Manufactury.

The ‘Chinese’ prospect and its culture of politics

As the composition of the prints are transformed from their square format into their landscapes, on a pictorial level, both the Kangxi poem and the prose-format descriptions of the process are removed. In turn, they are replaced with a short description to illuminate the process in English, such as ‘Plowing the Ground on which the Rice is to be Sowed’ [Fig. 1]. Although the explicative tone suggests an earnest inquisitiveness towards the agricultural process, the absence of a shared textual language makes it unsurprising that, throughout the British prints, the Chinese texts were understood as mere surface decoration rather than semiotic symbols. Indeed, such texts were eventually removed to focus on the visualisations of rice production. However, on an ideological level, this functions more significantly. Where the large poem written in running script calligraphy is understood as Kangxi’s assertion of the divine order of society, his mandate of heaven is removed. Instead, his watchful eye is turned into one in which the British viewer’s gaze is superimposed onto the scene.

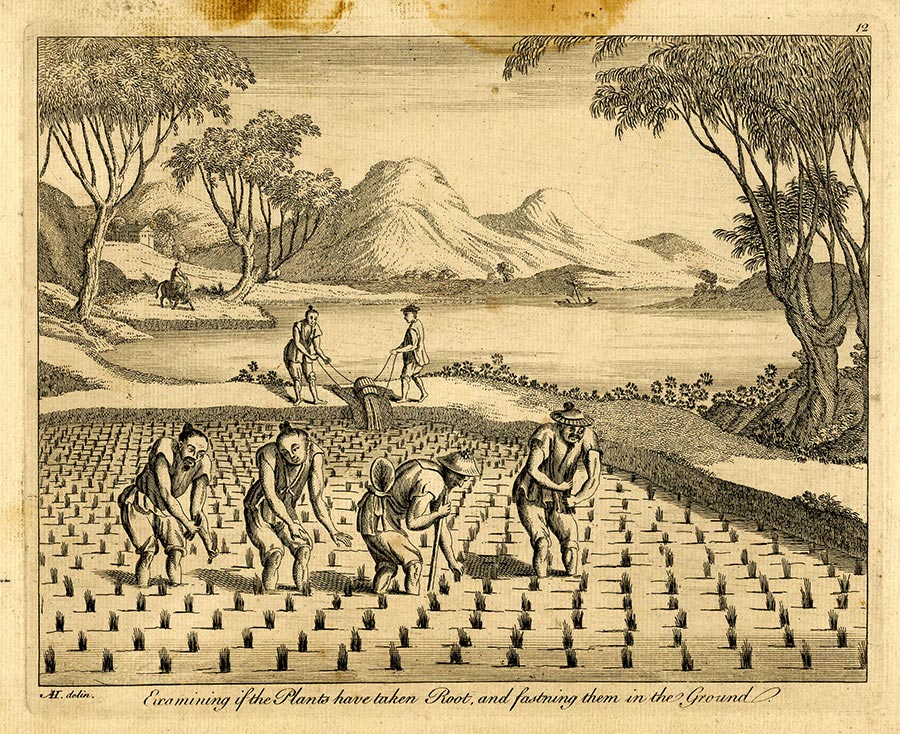

Figure 4 and Figure 5 both share a sense of orderliness in their compositions, as the labourers appear without a trace of dirt. Notably, June’s picture adheres to the principles of the Georgic, defined by man’s role in nature to transform physical labour into material products [Fig. 4]. In the foreground, with their backs hunched over, the farmers capture the viewers’ attention. As the rice plants are arranged along a grid formation, following the rules of linear perspective, they become smaller as they recede in space. Other details, such as the man with an ox in the distance, draw the eyes through a sinewy path towards the horizon line, towards the open view.

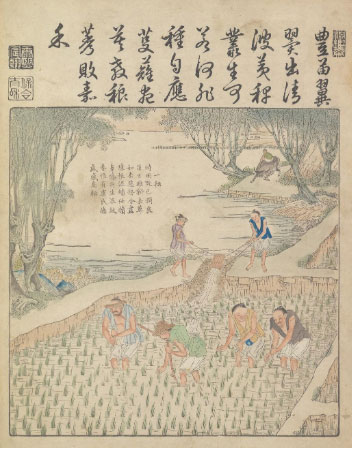

Meanwhile, framing the scene with mulberry trees, Jiao designates the delicate barks through a series of sinewy strokes, almost resembling a calligraphic performance within the literati painting tradition [Fig. 5]. In later scenes, these mulberry trees become integral to understanding the processes of silk production, as they are harvested to feed the silkworms. However, when absorbed into the English medium, the details of the mulberry tree hollows are lost [Fig. 7], as the bifurcations of the tree trunks recall an ambiguous vision of birch, or even elder trees.

In the late 18th century, British naturalists arrived in China anticipating its rich flora and fauna, keen to classify and collect samples, to bring this knowledge back to England. 10 With great public interest in ‘exotic’ flora, it is perhaps surprising that instead of replicating and recognising the topographical traditions of the Kangxi Gengzhi tu, the unusual plants were transformed into those generic – or ‘natural’ – to the landscapes that June’s audiences would have known. I argue that it is within this inevitable slippage in their discourses of interpretation that June reveals the tension in renditions of the picturesque. Firstly, within this framework, the uniqueness of a view, embodied through its ruggedness, had to be underscored within a framework of applicable formal elements derived from European art. Consequently, in the assumption of the British gaze towards the ‘Chinese’ landscape, there is an implicit establishment of the hierarchy of the generalising British landscape aesthetics over the Chinese particularities.

By conveying and beautifying local differences, The Rice Manufactury turns the distant and unfamiliar into the approachable. The prints do not only establish a gaze of possession over the landscape of Chinese labour; they also also aestheticise it. At this time, concurrent to the republication of The Rice Manufactury as A New Book of Landscapes, the genre of the landscape was accessible and was widely consumed, appealing to the eye as a scene of humble English rural scenery. ‘China’ was now made accessible to members of the middling classes. Studying the relationship between landscape paintings and the landed gentry, the social historian John Barrell argued that the ‘naturalisation’ of man into his landscape proves a natural theology wherein the rural poor were continually obliged to express their gratitude and obedience to the landowners. 11 In turn, the viewers assume the gaze of the rich landowner. By implication, infused in this gaze is the underlying motivation of land possession, where the viewer gazes in comfort toward a harmonious scene of work that is deemed morally and aesthetically satisfying.

Patterns of thought: ‘China’ and ‘Britain’

When discussing the British Empire in Asia, it is often the high imperialism of the late 19th-century British Raj or the occupation of Hong Kong that stands for the colonial project. However, art historians have oft neglected to analyse the works of art leading up to formal colonisation within this larger imperial motivation, where the British underwent new imaginings in their visions of China, which eventually culminated in the Macartney Embassy. Given the centrality of print culture in fuelling the identity and consciousness of the British public, we can observe how constructed visions of colonial landscapes were integrated within this tradition of disseminating ideas.

In the late 18th century, first runs for major political printsellers were conventionally between 500 to 2000 impressions. 12 Considering the republication of The Rice Manufactury in 1794, we can assume that rice cultivation prints were seen by an even greater number of members of the British middling classes and public. Relatively cheap to produce and sold for little money, prints proved a large viewership potential, providing ample medium in which ideas could be widely circulated. After the mid-18th century, in response to growing print markets in Europe, local English designs riddled with nationalist sentiment and patriotic subject matter proliferated. 13 Such trends are visible throughout the works commissioned by John Bowles, who also typically commissioned images of maps, national heroes, and historic sites. It is in this context that prints played a vital cultural role in elevating the intellectual and moral achievements of the British people, as a means of constructing and bolstering an ambitious view of national reach.

Where pictorial tensions of the ‘foreign’ collided with the ‘native,’ the imperial historians Catherine Hall and Sonya Rose also noted the importance of feeling ‘at home’ to ease and strengthen the myth of unity across the British Empire. 14 If notions of domesticity helped to mediate the moral uneasiness of British empire-building, then similarly, June’s prints situate visually the viewers’ ‘home’ within the land of ‘China.’

In this way, China is historicised not as a place of its people but a land of productive work. Viewed through print commodity, China is framed and trapped in the imperial gaze as a land of commodities, as a simultaneously demystified yet fantastical land of productivity and labour. From their conception, the Kangxi Gengzhi tu were fictive and not representative of Chinese society. The images did not merely function didactically to explain the steps of rice and silk production, but also asserted Kangxi’s ambition and explicated a method for an economically prosperous society – in which their reality differed from the images. Works like The Rice Manufactury, casting the Chinese in a curious light, generated a new imaginative space – both pictorially and in the geographical imagination – for viewers.

Linking back to Blake’s famous poem Jerusalem, John June’s employment of British landscape aesthetics reframed the laborious effort of the Chinese farmers – as acknowledged by Emperor Kangxi – into an English ‘green and pleasant Land.’ In tandem with changing ideas of China, projections of the British self were negotiated from this shifting grid of pictorial relations, from the Kangxi Gengzhi tu to John June’s The Rice Manufactury, trapping the process of Chinese rice cultivation within the British gaze of curiosity. At the same time, such differences were cast in tension – by nature, the subjects amplified the question of difference, they were to be made palatable by the growing British Empire, to potentially be seen as also British. It was this imagination that acted as a conduit for Britain, her art, and her desire for Empire.

Ashleigh Chow is an independent writer and art historian. She received her MSt in History of Art and Visual Culture from the University of Oxford in 2023 and lives in London. Email: ashleigh.yl.chow@gmail.com

Fig. 4: John June (active. 1744-1775), printed by John Bowles (1701?-1779), ‘Examining if the Plants have taken Root, and fastning them in the Ground’, The Rice Manufactury, c. 1770s, etching on paper, British Museum, London (Photo: British Museum, London) © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Meanwhile, framing the scene with mulberry trees, Jiao designates the delicate barks through a series of sinewy strokes, almost resembling a calligraphic performance within the literati painting tradition [Fig. 5]. In later scenes, these mulberry trees become integral to understanding the processes of silk production, as they are harvested to feed the silkworms. However, when absorbed into the English medium, the details of the mulberry tree hollows are lost [Fig. 7], as the bifurcations of the tree trunks recall an ambiguous vision of birch, or even elder trees.

Fig. 5: Jiao Bingzhen 焦秉貞 (active c. 1680-1720) , ‘The First Weeding (yiyun) 一耘’, Kangxi Imperially Commissioned Pictures of Tilling and Weaving, coloured woodblock print on paper, Library of Congress, Washington, DC (Photo: Library of Congress, DC).

In the late 18th century, British naturalists arrived in China anticipating its rich flora and fauna, keen to classify and collect samples, to bring this knowledge back to England. 10 With great public interest in ‘exotic’ flora, it is perhaps surprising that instead of replicating and recognising the topographical traditions of the Kangxi Gengzhi tu, the unusual plants were transformed into those generic – or ‘natural’ – to the landscapes that June’s audiences would have known. I argue that it is within this inevitable slippage in their discourses of interpretation that June reveals the tension in renditions of the picturesque. Firstly, within this framework, the uniqueness of a view, embodied through its ruggedness, had to be underscored within a framework of applicable formal elements derived from European art. Consequently, in the assumption of the British gaze towards the ‘Chinese’ landscape, there is an implicit establishment of the hierarchy of the generalising British landscape aesthetics over the Chinese particularities.

By conveying and beautifying local differences, The Rice Manufactury turns the distant and unfamiliar into the approachable. The prints do not only establish a gaze of possession over the landscape of Chinese labour; they also also aestheticise it. At this time, concurrent to the republication of The Rice Manufactury as A New Book of Landscapes, the genre of the landscape was accessible and was widely consumed, appealing to the eye as a scene of humble English rural scenery. ‘China’ was now made accessible to members of the middling classes. Studying the relationship between landscape paintings and the landed gentry, the social historian John Barrell argued that the ‘naturalisation’ of man into his landscape proves a natural theology wherein the rural poor were continually obliged to express their gratitude and obedience to the landowners. 11 In turn, the viewers assume the gaze of the rich landowner. By implication, infused in this gaze is the underlying motivation of land possession, where the viewer gazes in comfort toward a harmonious scene of work that is deemed morally and aesthetically satisfying.

Patterns of thought: ‘China’ and ‘Britain’

When discussing the British Empire in Asia, it is often the high imperialism of the late 19th-century British Raj or the occupation of Hong Kong that stands for the colonial project. However, art historians have oft neglected to analyse the works of art leading up to formal colonisation within this larger imperial motivation, where the British underwent new imaginings in their visions of China, which eventually culminated in the Macartney Embassy. Given the centrality of print culture in fuelling the identity and consciousness of the British public, we can observe how constructed visions of colonial landscapes were integrated within this tradition of disseminating ideas.

In the late 18th century, first runs for major political printsellers were conventionally between 500 to 2000 impressions. 12 Considering the republication of The Rice Manufactury in 1794, we can assume that rice cultivation prints were seen by an even greater number of members of the British middling classes and public. Relatively cheap to produce and sold for little money, prints proved a large viewership potential, providing ample medium in which ideas could be widely circulated. After the mid-18th century, in response to growing print markets in Europe, local English designs riddled with nationalist sentiment and patriotic subject matter proliferated. 13 Such trends are visible throughout the works commissioned by John Bowles, who also typically commissioned images of maps, national heroes, and historic sites. It is in this context that prints played a vital cultural role in elevating the intellectual and moral achievements of the British people, as a means of constructing and bolstering an ambitious view of national reach.

Where pictorial tensions of the ‘foreign’ collided with the ‘native,’ the imperial historians Catherine Hall and Sonya Rose also noted the importance of feeling ‘at home’ to ease and strengthen the myth of unity across the British Empire. 14 If notions of domesticity helped to mediate the moral uneasiness of British empire-building, then similarly, June’s prints situate visually the viewers’ ‘home’ within the land of ‘China.’

In this way, China is historicised not as a place of its people but a land of productive work. Viewed through print commodity, China is framed and trapped in the imperial gaze as a land of commodities, as a simultaneously demystified yet fantastical land of productivity and labour. From their conception, the Kangxi Gengzhi tu were fictive and not representative of Chinese society. The images did not merely function didactically to explain the steps of rice and silk production, but also asserted Kangxi’s ambition and explicated a method for an economically prosperous society – in which their reality differed from the images. Works like The Rice Manufactury, casting the Chinese in a curious light, generated a new imaginative space – both pictorially and in the geographical imagination – for viewers.

Linking back to Blake’s famous poem Jerusalem, John June’s employment of British landscape aesthetics reframed the laborious effort of the Chinese farmers – as acknowledged by Emperor Kangxi – into an English ‘green and pleasant Land.’ In tandem with changing ideas of China, projections of the British self were negotiated from this shifting grid of pictorial relations, from the Kangxi Gengzhi tu to John June’s The Rice Manufactury, trapping the process of Chinese rice cultivation within the British gaze of curiosity. At the same time, such differences were cast in tension – by nature, the subjects amplified the question of difference, they were to be made palatable by the growing British Empire, to potentially be seen as also British. It was this imagination that acted as a conduit for Britain, her art, and her desire for Empire.

Ashleigh Chow is an independent writer and art historian. She received her MSt in History of Art and Visual Culture from the University of Oxford in 2023 and lives in London. Email: ashleigh.yl.chow@gmail.com