Globalized economy and the Chinese national oil companies

In recent years, with the successful implementation of the Going-Out policy, Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs) have made great progress in participating in the global market and competing with international companies. Among the SOEs, two Chinese national oil companies, China Petroleum and Chemical Corporation (Sinopec) and China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC), were ranked in the global top five companies of 2015, in terms of assets and revenue.1 . The rationale behind the expansion of the cross-border activities of China’s national oil companies (NOCs) is mainly China’s energy security, prompted by China’s resource scarcity and growing energy demand.

The cross-border activities of Chinese NOCs have raised a debate regarding the role of the state in the transnational activities of its national oil companies. A majority of scholars contend that Chinese NOCs are of a hybrid type, since they only partly resemble international oil companies (IOCs) that independently conduct cross-border activities; but this article argues that the Chinese government can in fact override all NOC decision-making, and Chinese NOCs can therefore better be characterized as state-led companies. The state retains the authoritative power in managing not only the domestic development of the NOCs, but also their cross-border activities in other resource rich countries. It is assumed that these activities are part of China’s ‘statist’ globalization, whereby the state creates access to energy resources in other countries for the NOCs, and the NOCs help to project power, realizing the state’s political and economic objective.2 The successful trans-nationalization of Chinese NOCs shows that they are more capable of obtaining oil resources across the global range than international oil companies, but it also demonstrates the success of the Chinese government’s control.

From 1904 to 1948, oil production in China was only 2.8 million tonne, while oil import was 28 million tonne.3 With the successful exploitation of the Karamay and Daqing oil fields in the 1950s, oil production notably increased, making China an oil self-reliant country. In 1955 the Chinese government established its Ministry of Petroleum Industry (MPI), which was responsible for managing oil-related assets, planning oil exploitation projects and enacting national oil strategy. In 1982, the China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC) was established from the offshore assets of MPI. In 1983, the Sinopec Group was created from the downstream assets of MPI and MCI (Ministry of Coal Industry and Ministry of Chemical Industry); in 1988, the China National Oil and Natural Gas Corporation was established to enhance onshore and upstream oil and gas production, which was later restructured into CNPC.4 Moreover, CNPC was assigned to take over the assets and tasks of MPI. This partial corporatization signifies that CNPC would not only be in charge of oil exploration projects, but more importantly, also enact national energy policy and coordinate the regional development of oil industry.

It is against this background that China’s NOCs were established. Compared to other International Oil Companies (IOCs), China’s NOCs can be characterized as quasi-governmental organizations, which disputes the assumption that Chinese NOCs are of a hybrid type. To better comprehend the nature of Chinese NOCs, it is rather important to concretize the intertwined relations between the NOCs and different government bodies.

Governance of Chinese NOCs

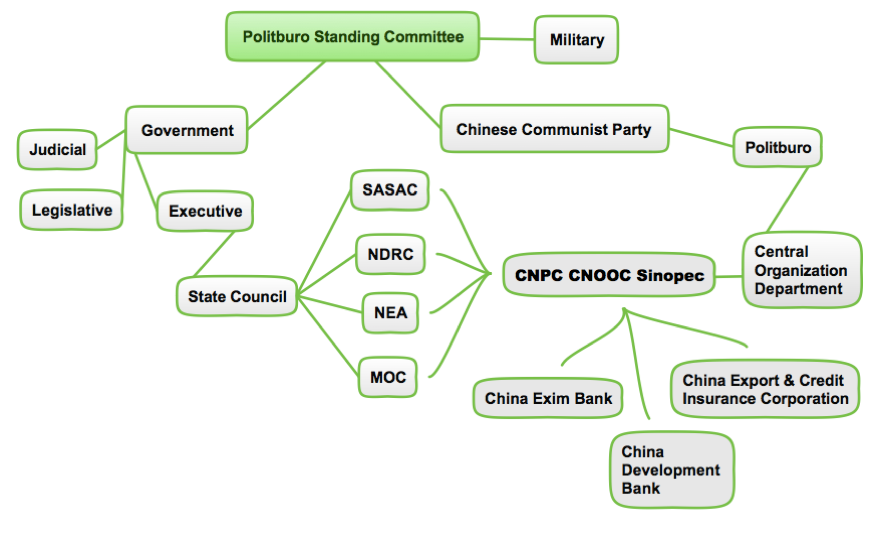

The corporate structure of Chinese NOCs is similar to many IOCs, however, the de facto decision-maker for NOCs is the Chinese government. In China, neither a moral order nor a legal system has been sufficiently internalized in order to regulate the behavior of state officials, which makes it difficult to understand China’s governance of the society and SOEs. Externally, different government departments are responsible for setting up macro-economic and social policy, while internally, the Communist Party of China (CPC) is embedded into the elite network of all government departments, which results in a more intransparent decision-making mechanism. Historically, the Chinese nomenklatura system stipulates that the Communist Party of China is omnipresent in managing and controlling the society in every field such as government, military and business.

The Politburo Standing Committee (PBSC) is the top decision-making body in China. Currently, PBSC consists of seven members elected by the Central Committee, and who include President Xi Jinping and Prime Minister Li Keqiang. However, in practice PBSC members are chosen by current leaders and Party elders, who ensure their interests are protected and allies well-chosen. As a consequence, the aforementioned political ruling elite is entrenched in every part of government, where they exert their influence to secure their political and economic interests. NOC board members are expected to be obedient to the Communist Party, and enact corporate strategy according to the party’s interests.

From a macro-level perspective, Chinese NOCs are generally supervised by several governmental entities including the State Council, State Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC), the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), the National Energy Administration (NEA) and the Ministry of Commerce (MOC). The State Council is the highest executive government body in China. The cabinet-like State Council is headed by the Prime Minster, four vice-premiers, five state-councilors and one secretary general.5 It has 25 subordinated departments, but some departments, such as SASAC, are considered to be ‘supreme ministries’ that are more essential and powerful than others.

Established in 2003, SASAC is the only department that is directly subordinated to the State Council. It was created to take on investment and administrative responsibilities for SOEs. SASAC is responsible for supervising NOCs, establishing corporate regulations, perfecting company structure, adjusting national economic policy and reforming SOEs. Currently, SASAC holds around 3.7 billion dollars of assets from its 116 flagship SOEs, including CNPC, Sinopec and CNOOC.6

SASAC retains absolute executive control over NOCs performance and selection of their board members. SASAC exercises its controlling power over allocation of remuneration, assets disposal and enactment of plans regarding commercial merges and shareholding acquisitions. NOCs must obtain permission from SASAC before conducting overseas investments, establishing joint ventures or mobilizing assets, activities through which SASAC can achieve the party’s political and economic interests.

The other three significant government bodies related to NOCs are the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), the National Energy Administration (NEA) and the Ministry of Commerce (MOC). NDRC, formerly known as State Planning Commission, is in charge of the overall macro-economic development of China and enacting guidance for restructuring the Chinese economic system. Meanwhile, the Energy Bureau branch of NDRC presents policy recommendations for NOCs’ overseas investments and other cross-border activities. Established in 2013, NEA is a new government entity that coordinates with NDRC in setting energy development policies. Domestically, NEA will research and publish energy-related information, participate in the process of sustaining domestic energy supply, and adjust energy policies in response to the global energy situation. As NOCs are vital entities that can assure China’s energy security, they must consult and obtain policy recommendations from NEA. Lastly, MOC participates in macro-economic development, providing financial support and policy recommendations for the central and regional governments. MOC is further related to the China Development Bank, Exim Bank of China, and China Export & Credit Insurance Corporation (Sinosure), all of which will provide financial and credit support for NOC transnational activities.

The Central Organization Department (COD) retains absolute authority in appointing and dismissing personnel in different ministries, provincial government branches, SOEs and universities. The Communist Party possesses a strict hierarchical list of political leaders and other candidates that are suitable to fill those positions. The most senior positions in SEOs – party secretary, chairman and chief executive officer – are all chosen by COD, and one person will often be simultaneously appointed as chairman and party secretary.

Since the Chinese government is responsible for ensuring China’s energy security, the CPC has institutionalized its control over strategy, board members and the corporate structure of NOCs. The criteria for leadership positions in NOCs include political reliability inside the CPC membership, and practical working experience related to the oil sector. It is clear that most China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) executives have the dual role of manager in the company and a membership of the CPC. For instance, Wang Yilin was elected as the Chairman of the Board of CNPC in 2015, and is also a member of the Central Commission of Discipline Inspection in the CPC; and Zhou Jiping served as the director of CNPC from 2011 to 2015, while simultaneously appointed as a member of the 12th Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC) from 2013 to 2018.7 . CNPC’s senior officers must be able to balance the company’s commercial interests and the CPC’s political and economic goals, and even prioritize the latter. In most scenarios, only by complying with CPC protocols and by acting in accordance with CPC interests can NOC board members be promoted and transferred to higher positions.

Concluding remarks

In order to assure China’s energy security, the Chinese government has enacted the Going-Out policy, in which NOCs have successfully achieved their trans-nationalization and played a pivotal role in obtaining more oil resources in the Middle East, Africa, Central Asia and Latin America. Moreover, Chinese NOCs remain under the supervision of the Chinese Communist Party. The management of NOCs is institutionalized through entities such as the State Council and the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission. The Central Organization Department plays a decisive role in appointing NOC board members and this allows the Chinese ruling elite in the oil sector to ensure the maximization of its interests. Furthermore, with the recent CPC reformation and large-scale anti-corruption movement in SOEs, it is without doubt that NOC board members are aware of the CPC’s desires, since ensuring the party’s general interests can help them get promoted. This mechanism has effectively concretized the governance of Chinese NOCs.

Changwei Tang, MSc Political Science, University of Amsterdam (changwei.tang.don@gmail.com).

This article is based on research conducted as a research assistant during a three-month affiliation with the Energy Program Asia (IIAS) in 2015.