Ghostwork

In one of our initial conversations with Aarti Sunder, she showed us a set of four photographs she had procured by posting a high-paying HIT, or human intelligence task, on a notorious online marketplace she’s been researching called Amazon Mechanical Turk—a crowdsourcing website that businesses use to hire geographically dispersed workers to perform discrete on-demand labor that computers are unable to do. She asked people to send her four images of their workspaces, taken looking inward from each corner of the room they sat in.

The COVID-19 pandemic had many people around the globe setting up home offices as a novel condition. Aarti, who was studying at MIT at the time, was in dialogue with friends and colleagues about what isolation from the communal context of the classroom or office, as well as what Zoom-enabled access into the private spaces of the home and the bedroom, might be doing to the nature of learning and work itself. In contrast to this experience of novelty brought on by quarantine regimes, the elimination of the office cubicle or the factory floor is a mainstay for a gig economy that essentially functions by outsourcing work to a remotely located crowd of individuals who are unable to know or interact with each other.

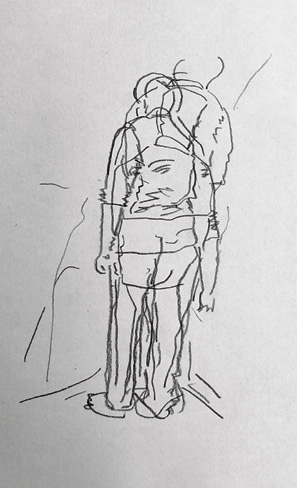

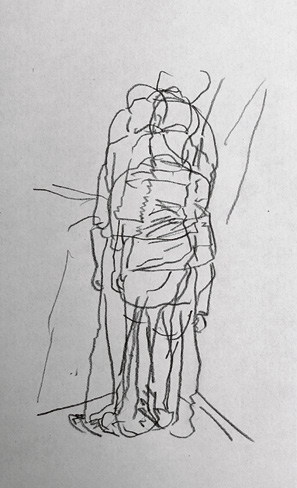

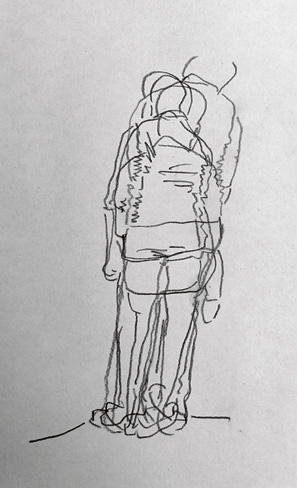

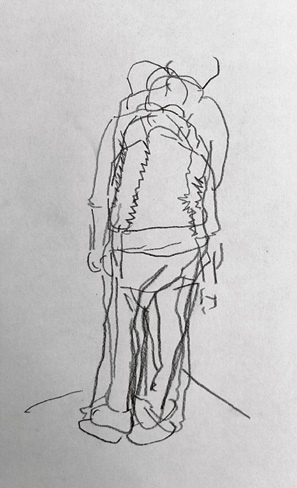

Eliciting images of the physical locations that people inhabit while performing click work via digital platforms, which are ultimately designed to keep them invisible and negate their existence, introduces a crack in a seemingly totalizing system. Aarti received around 20 submissions in response to the assignment she posted, but she singled out one set that caught her attention. When I saw these photographs, I was struck and perplexed, and they have lingered in the back of my consciousness since. What did these pictures want, exactly? In that preliminary discussion, the images seemed to exceed our capacity for attributing language to what they were doing. And even Aarti’s subsequent and poignant analysis indicates that what they represent is that which supersedes what can be seen. These photographs are rendered here as sketches that Aarti has made by hand, and their handmadeness is a significant aspect [Figs. 1-4]. The reason she turned to drawing in this particular instance is that she is unsure about releasing these images into the public domain in photographic form. This might have something to do with what she calls their potency, and in addition, what I see as their immediacy.

How does this relate to Natasha, the biennale we are making? During one of our early curatorial discussions, Ala flashed a website called This Person Does Not Exist 1 onto the shared screen, and June helped me identify my extreme unease – or was it terror? – in response to its content within the uncanny valley. This Person Does Not Exist is a repository of high-resolution images of seemingly real people generated by powerful artificial intelligence technology. Each photograph is a composite of many other people, and the single person it portrays is not of this world in the way that you and I might be. Who or what is the referent? Our relationship to the experience of looking at the representation of a visage is undone and that which is indexical about the genre of portrait photography explodes into impossible fragments. The faces on the website express feelings, but it is safe to claim that the entities in the images do not possess the capacity to have them.

In aesthetics, the uncanny valley denotes a negative emotional response with regard to one’s relation to an object, based on the object’s degree of indistinguishability from a human being. One of the things we have hoped to do by giving the Singapore Biennale 2022 a name that is generally associated with a person is to assess our assumptions of the fundamental conceptual category of the stable unitary subject that personhood implies, to think of our relation to the earth and the cosmos in more material and temporal terms. Sometimes we insist in public discussions that this “Natasha” is not a person, but we maintain that visiting Natasha is an invitation to encounter a presence nonetheless. What is this presence composed of? How is it felt? From where has it come and to what time does it belong? While This Person Does Not Exist opens onto a terrain I am hesitant to enter, Aarti’s project compels us to confront the “intentionally hidden and opaque forms of labor” called ghostwork and to feel its presence across various platforms that claim to be computer-operated. It is widely understood that the commonplace notion of artificial intelligence rests on negating the material and human costs that have gone into machine learning. “The word ghost here,” she writes, “indicates that it is not just the physical absence of a person doing a particular job, but the pretense that such a person does not even exist; the silent laboring hand behind the magic of technology; the silence that requires spontaneity, creativity, and cultural interpretation.” 2

Nida Ghouse is a writer and curator whose projects span mediums and disciplines, experimenting with ways of engaging artistic practices, in relation to activating materials and sites. E-mail: nghouse@bard.edu

Fig. 1-4: Layered Light Trace, series of drawings by Aarti Sunder, 2022. “To be willing to read in between the shapes, to see the formation of the human body once again and be reminded of it as a part of the process of automation, where the fight is to identify oneself as a visible node, is a violent process. There is something intimate about these images, yet impersonal. The images contain the violence of forced hiddenness, but also the power to willingly remain unidentifiable. This is why these images are so potent – they urge the viewer to contend with the creativity of the hidden hand all the while signaling towards the harsh apparatus that enables it.” – Aarti Sunder