Gendered Fields of Constitutional Politics: Women’s Routines and the Negotiation of Territorial Belonging in Nepal’s Far Western Tarai

Recent constitution writing and province delineation in post-conflict Nepal inspired popular reflection on the meaning of belonging to the Nepali nation-state, bringing sensitive questions around social and spatial origins to the fore of national and sub-regional politics. In the borderlands of Kailali district in Nepal’s Far Western Tarai, settlement dynamics amongst Indigenous Tharu and Hill-origin persons has generated a charged scene for adjudicating constitutional provisions for social inclusion and territorial recognition. Women navigate legacies of migration and social difference during their daily mobilities and everyday routines, extending national politics into gendered fields of labor and belonging.

Origins and destinations

“Where have you come from?” is a standard greeting exchanged by friends and strangers crossing paths on Nepal’s roads and foot trails. Whether asked at the outset of a day’s trip to agricultural fields or at the end of a jolting bus ride to Kathmandu, answering it invites the respondent and questioner into a social geography facilitated through idiosyncratic relationships to places near and far.

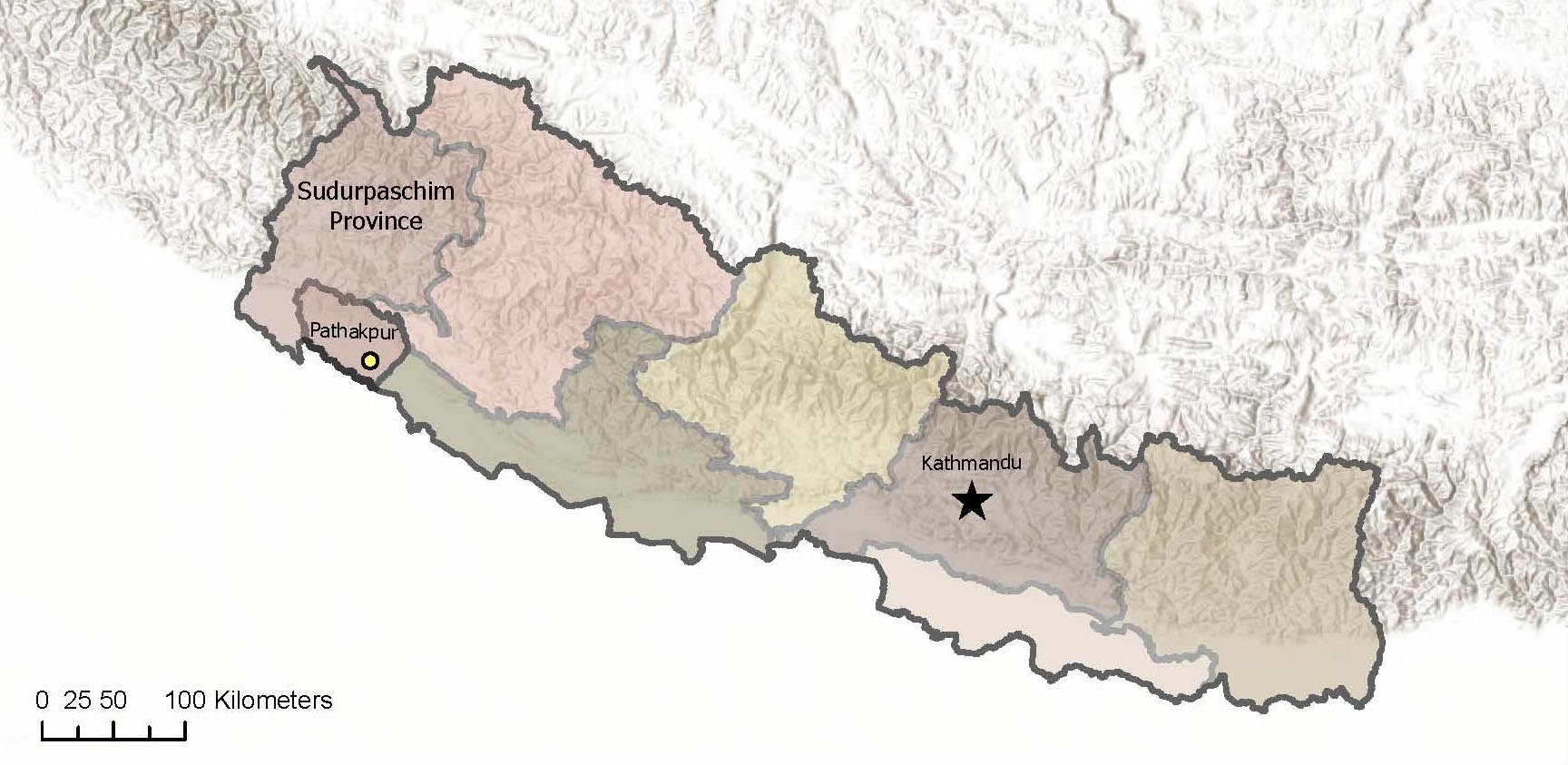

In regions that have experienced repeated waves of migration and settlement, such as the lowland Tarai-Madhes region along the southern Nepal-India border [Fig. 1], talking about where one starts the day, and where one might end up, can facilitate a sense of connection amongst people moving across a shared but differently experienced landscape. It can also shift conversation toward another kind of origin: family. While ostensibly seeking a point of connection between unfamiliar persons, such inquiries probe for information about an individual’s affiliated caste and ethnicity, which can either be the basis for inclusion in or exclusion from the social world of questioner and respondent.

Throughout much of Nepal, questions about social and spatial origins are a routine part of daily life. Yet in the decades since the end of the ten-year conflict between the Communist Party Nepal-Maoist and the Government of Nepal in 2006, such inquiries have gained heightened significance. In the aftermath of the conflict, Nepali citizens embarked on a joint project of constitution writing and state restructuring in the hopes of resolving longstanding social tensions in Nepal surrounding the discrimination of marginalized groups and regional underdevelopment. 1 Over the course of two elected Constituent Assemblies between 2008 and 2015, lawmakers worked to design constitutional provisions for social inclusion and demarcate new federal provinces. 2 Arranging legal boundaries for social inclusion and territorial boundaries for provinces raised important conversations amongst the Nepali public about the past and present identity of the Nepali nation-state and ways of belonging to it. For many, this was an anxious time filled with competing visions of Nepal’s future form. 3 Constitutional and territorial models of the future Nepali state diverged strongly in the southern Tarai-Madhes region. Along the southern borderlands, competing demands for federal province-based territorial recognition raised by Indigenous, caste Hindu, and other regional Tarai-Madhes groups brought lived experiences and historical legacies of Tarai-Madhes migration and settlement to the foreground of contemporary regional and national constitutional politics.

Kailali district, in the Far Western Tarai, was especially affected by Nepal’s post-conflict federalism politics. The Tharu community, an Indigenous Tarai group, supported the creation of Tharuhat or Tharuwan, a province recognizing the Tarai as the Tharu homeland. Meanwhile, other residents of the region, many of whom who had origins and ancestors in the Hills, advocated for the formation of a Hill-Tarai integrated province through a regional political movement called Akhanda Sudurpaschim, or United Far West. In September 2015, the constitution was promulgated and a new map of federal provinces was demarcated. Many residents of the Tarai-Madhes, including those of Kailali district, voiced their dissatisfaction with the map and constitution, proclaiming that it failed to generate the socio-political transformation promised by the state restructuring project. The map did not demarcate provinces championed by Indigenous peoples, such as the Tharu. Instead, six of the seven provinces included on the final federal map followed the integrated Hill-Tarai model for provinces supported by groups such as the United Far West. The lack of recognition for the homelands and territorial attachments of Indigenous peoples on the federal map undermined public faith in provisions for social inclusion outlined in the constitution. In the months and years after the constitution’s promulgation, unresolved tensions around the federal system and the federal map thickened the air in Kailali. They resonated in mundane interactions and conversations, extending the field of politics into the routines of everyday life.

Routine politics

In Fall 2016, a year after the promulgation of the Constitution of Nepal and a year before the delineation and implementation of local federal units, my Tharu confidants Meena and Anju and I set out to spend the afternoon gathering fodder grass in a neighbor’s field a mile or so from the women’s homes in a village (which I anonymize as Pathakpur) in eastern Kailali district. Collecting fodder grass was a daily activity for us [Fig. 2 and 3]. I learned how to identify good and poor grasses for goats and buffaloes and how to tell the difference between familiars and strangers according to Meena and Anju’s studied criteria. On this afternoon, Meena and Anju were joking loudly while filling their repurposed grain sacks with grasses, and they missed the sound of approaching footsteps pushing through the tall wheat plants. She startled us, this woman, small and bent, when she tossed down her woven basket from her back and lifted her arms up in greeting. Rising steadily with her sickle in hand, Meena looked the woman up and down before calling out to her: “Budhi, kahaa batta aayo?” (Nepali for “Old woman, where have you come from?”). With her own sickle, the woman gestured behind her to a cluster of mud-plastered houses barely visible on the horizon. The distant houses were established by people who had settled in Kailali from the Far Western Hill district of Doti. Meena took notice of the grass filling the woman’s well-used basket, and I watched Meena calculate the size of the load to the woman’s frail fame. “Who’s helping you?” Meena asked, again in Nepali. A short thin boy rose soundlessly from the field. His lean legs kicked out at the basket lying at the older woman’s feet. “This one helps me,” she responded rustily. In short sentences she told how she came from Doti two months ago to live with her son and his family after her husband died. “There was nothing in the hills for me after his death,” she explained, “only drought and hardship. But here too life is hard,” she added, gesturing to her basket. Sharing a look with Meena, the woman kneeled to the ground while the boy hefted the load onto her back. With a heave, she lifted her basket and secured its strap to her forehead, nodding to us in farewell.

Fig. 2: Nepal’s Far West Province (Sudurpaschim

Province) featuring Kailali district and the

approximate location of Pathakpur (a pseudonym).

Fig. 3: Two agricultural plots where

Mena and Anju collect fodder.

Meena and Anju sucked their teeth watching the woman’s head duck in and out of sight across the fields. Her presence that afternoon gave us a point of contrast to mark the differences between our lives. For Meena and Anju, the fields were part of their daily realm of work and routine, and they reached them from Tharu-established villages where they have lived nearly all their lives. Their movements into and out of the fields weave the landscape into an ever-tightening social fabric they feel as home. But it is a landscape where they have grown accustomed to speaking first in Nepali, not Tharu, when encountering an unfamiliar person like the older woman, whose own mother tongue is likely not Nepali but a Far Western Hill language such as Doteli. As we headed for our own house, Meena turned to me and said, “I feel so sad for these Pahadi [Hill origin] women. They come here lost.”

Her words reminded me of the poem “Sala Pahadme Kya Hai?” (“What’s in these Bastard Hills?”) by Nepali poet Minbahadur Bista, published in 1983:

Young sons are walking out,

leaving the places they were born,

taking loved ones with them,

carrying bags, neatly tied

with red kerchiefs on their shoulders,

khukhuri knives hang from their waists,

dull and unpolished for years;

they tell their sick old parents

to look after homes, homes which are lifeless. 4

In this small encounter, Meena’s question – “Where are you coming from?” – extended into an unasked, yet eventually answered, question: “Where are you from?” They were asked to ascertain spatial position on the landscape as well as social position among the multi-stranded ties people have to Kailali. Their significance stands in further relief in the context of Kailali district’s importance as a popular destination for internal and international migration and as a historically important frontier of the Nepali nation-state.

Basai-sarai (residence-shift)

In Kailali, the Tharu, an Indigenous Tarai group living along both sides of the international border, are recognized as the area’s original residents. Alliances brokered with Tharu elites in the 18th century and earlier afforded political powers in North India and Kathmandu a toe hold of authority in the southern lowlands. Yet, for the most part, distance, dense forests, and virulent malaria slowed the arrival of non-Tharu to the Far Western Tarai over what is thought of as the long 19th century. Instead, a seasonal rhythm of movement into and out of the region was observed as folks, predominately men, from the Hills and Gangetic Plain arrived over winter months to grow crops and trade before the onset of monsoon and malaria transmission.

However, by the mid-20th century, the Nepali government had begun to experiment with technologies of environmental management, most importantly indoor residual spraying with DDT for mosquito population control. The advent of malaria eradication in the Tarai altered the rhythm of seasonal mobility and encouraged peoples from near and far to move into Kailali for land and opportunity. 5 The Nepali government attempted to keep the wave of population transfer in check through techniques of population control, such as the creation of planned settlement colonies and land redistribution programs, as well as punishing individuals living on state-controlled forest land with jail and the destruction of their homes and property. Eventually these measures gave way, and Kailali’s population boomed in the second half of the 20th century, rising from 128,877 in 1971 6 to 616,697 in 2001. 7

While historians of Nepal focus on the mid-20th century as the moment of the Tarai’s demographic transformation, migration into the Far Western Tarai is still underway. The 2021 Census of Nepal 8 indicates that migration or basai-sarai (residence-shift) remains high in Kailali. Out of a population of 904,666, Kailali counts 571,061 persons as enumerated in the same place (local administrative unit) where they were born. Respondents indicating that they were born elsewhere in Kailali district from where they were enumerated numbered 71,747. A much higher number of respondents (245,841) state that they were born elsewhere in Nepal. Respondents relating that they were born outside Nepal, likely in neighboring India, numbered 15,626.

Comparing results from the 2011 and 2021 censuses underscores the continued shifts of people and language use in Kailali district. In 2011, 41 percent of the total population of Kailali reported speaking Tharu as a first language. The 2021 census used more discrete language categories than recorded in earlier censuses, differentiating Tharu and Rana Tharu languages. Yet even when combining numbers of Tharu and Rana Tharu first language speakers, the overall percentage of reported first-language Tharu speakers in Kailali decreased to 38 percent in 2021. Meanwhile Nepali first-language speakers increased between 2011 to 2021 from 27 to 36 percent. Languages such as Doteli, Acchami, Magar, Maithili, and Hindi were spoken by over 0.5 percent of Kailali residents in both 2011 and 2021, although numbers of Doteli speakers decreased overall from approximately 19 to 14 percent. These results suggest that significant monitories of Kailali residents include people with linguistic ties to the Far Western Hills (Doteli, Acchami, Magar), the Central and Eastern Tarai (Maithili), and North India (Hindi).

The municipality I have anonymized as Pathakpur, however, has experienced less demographic change between 2011 and 2021 than the district overall, maintaining a majority Tharu-speaking population. Before being consolidated into the newly established Pathakpur municipality in 2017, the two Village Development Committees which today make up Pathakpur were recorded by the 2011 census as having a much higher percentage of Tharu residents than the district average. Eighty-five percent of the population in one unit and 72 percent in the other reported being Tharu. They also claimed Tharu as their mother tongue, making Tharu the most spoken language in both units. After the Tharu language, Doteli, Nepali, and Achhami were recorded to be spoken most frequently as a first language in both administrative units in 2011. In 2021, 79 percent of Pathakpur residents identified as Tharu and reported the Tharu language as their mother tongue. Meanwhile, 4407 persons selected Doteli as their first language, followed by 2610 Nepali and 539 Achhami first-language speakers. These linguistic signs tell of near and distant ancestral origins for people who live in Pathakpur. But they also communicate continuity in place for Pathakpur’s Tharu and Hill origin residents. The combination of residence shift and intergenerational place-making underscores the intensity of territorial politics around belonging to Kailali in the era of constitution writing and federal restructuring.

Signposts

Asking someone about where they have come from prompts a follow-up question: “Where are you going?” Where are places like Pathakpur, districts like Kailali, and women like Meena, Anju, and the old Pahadi woman headed in the newly federal Nepal? The future is uncharted. But there are signs that the future will look very different from Nepal’s past. Already, Pathakpur has aligned itself with the pro-Tharu Nagarik Unmukti Party, the People’s Freedom Party. The Nagarik Unmukti Party was established by Ranjeeta Shrestha on behalf of her husband, the Sudur Paschim Province House of Representatives lawmaker and activist Resham Chaudhary. Resham Chaudhary was released from prison in June 2023 after being delivered a life sentence for his alleged involvement in the 2015 Tikapur Incident, in which security personnel and a toddler were killed during fighting that broke out at a Tharuhat/Tharuwan rally on the eve of the constitution’s promulgation. The Mayor and Deputy Mayor of Pathakpur in 2023 also belong to the Nagarik Unmukti Party and are Tharu. The election of Tharu candidates and the use of Tharu language in government offices has removed barriers for Tharu access to local government that had long been felt in the region.

Tharu speakers, like Meena and Anju, and Pahadi residents in Pathakpur will continue to navigate each other’s lives across a district landscape they share as a consequence of the ebbs and flows of migration, settlement, and nation-state building in Nepal’s Far Western Tarai. But their negotiations today can be seen to proceed on more even footing than in the past. Who can answer “Where are you going?” with so many destinations in sight?

Amy Johnson is Assistant Professor of Anthropology at Georgia College and State University. Her research explores everyday negotiations of environmental and political changes in Nepal, with a particular focus on gender, kinship, and state-making. Email: amy.johnson@gcsu.edu