A forgotten place

Chinese art underwent a period of thorough reform at the turn of the 20th century. It was a time when the self-confidence of Chinese culture was being shaken to its core by the influences of the West and the ensuing impact of Western civilization. Chinese art – with its age-old tradition of subject matters, techniques, aesthetics and materials – was inevitably confronted with the problem of how to respond to the needs of a changing society.

The major challenge, as noted by Michael Sullivan, was “how to modernize, which has meant to a great extent how to Westernize, while remaining her essential Chinese self”. 1

Scholarship on 20th century Chinese art has hitherto concentrated much on the attitude of Chinese artists towards the West, the modernity, and China’s own tradition. In the eyes of many art historians, the notion of the West in the discourse of 20th century Chinese art could be traced back to two sources – Europe and Japan – for these were the primary locations where most Chinese artists chose to study abroad at that time. Deemed as the trigger of the modern Chinese art reform, European and Japanese influences have thus long been occupying center stage of modern Chinese art studies.

However, at the same time that Chen Duxiu (1879-1942) initially advocated using the realism found in Western art to reform Chinese painting, European art was heading in the opposite direction, away from realism. So how to properly measure the impact of Western art on Chinese modern art reform? What changes did Chinese art go through in the pursuit of art reform? The pre-eminent 20th century Chinese artist Gao Jianfu (1879-1951) once suggested that the ‘new Chinese painting’ should embrace elements from all cultures. Yet in reality, owing to the dominant position of the Western-oriented modernity theory, the ‘new Chinese painting’ could hardly demonstrate the intended panoramic view of China’s international artistic exchanges of the 20th century. Overshadowed by the European and Japanese narratives, intra-Asia artistic exchanges have not received the attention they deserve. In the wave of 20th century anti-imperialism and pan-Asianism, interactions among Asian countries have been crucially important to China in finding its own way to modernize. Among these intra-Asia interactions, the engagements between China and India are worth exploring in more detail, particularly during a time when the two oriental civilizations were both confronted with pressures from the West and the problem of modernization.

Why India matters to the modern Chinese art reform?

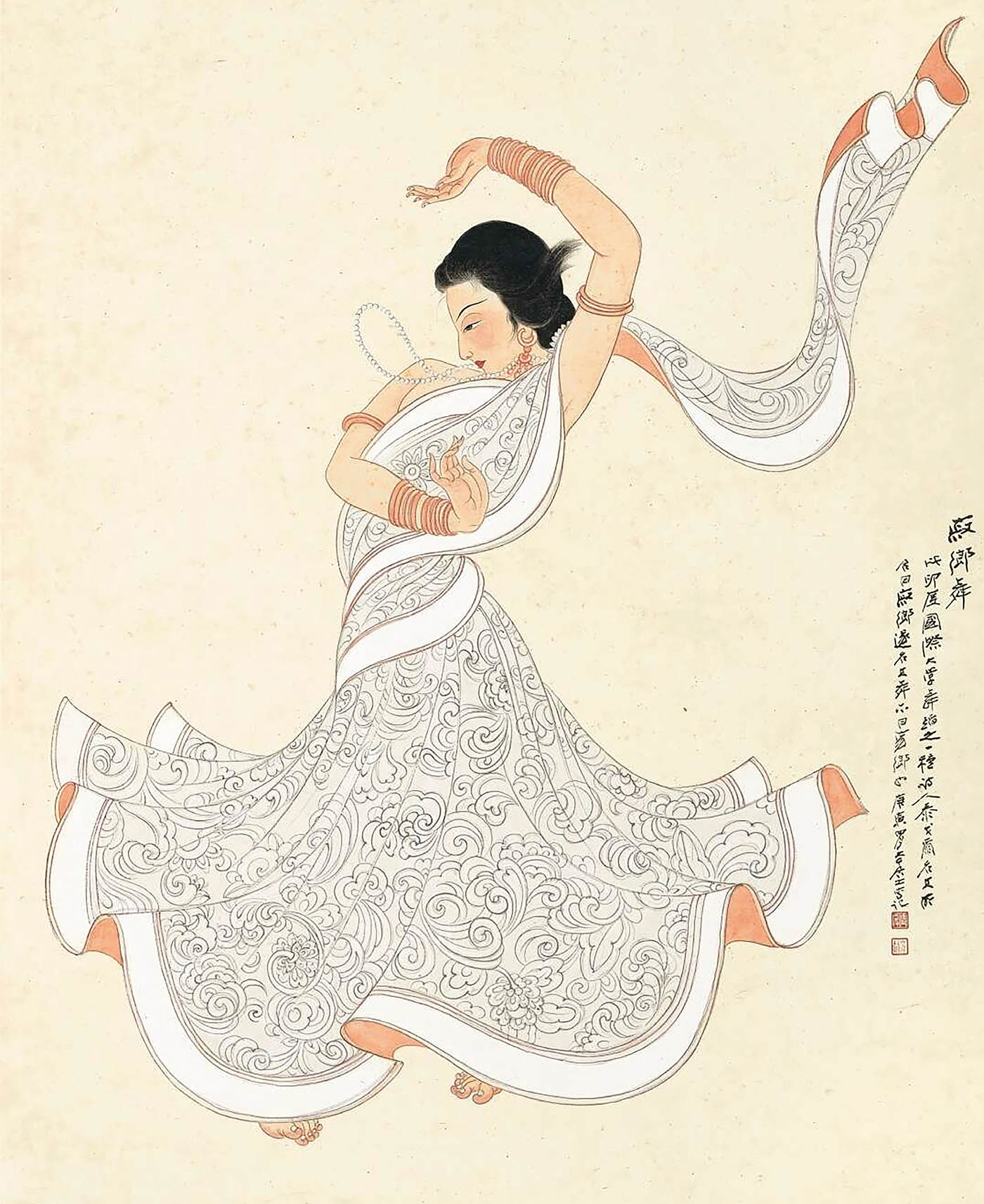

Since at least the first millennium, Indian art, along with the introduction of Buddhism, had already taken root in Chinese art. The splendid Dunhuang mural paintings make an emblematic case that reflects how Indian figural elements of anatomy and linear perspective influenced Chinese figure painting at an early stage. In the 20th century, when traditionalism began to be held as a modern stance, the epochal artist Zhang Daqian (1899-1983) – who had a desire to seek for the primitive vibrancy of Chinese art – chose to re-examine the much more time-honored tradition of figure painting in the Sui and Tang dynasties, rather than sticking to the dominant landscape painting tradition that had flourished since the Song dynasty. From 1941 to 1943, Zhang sojourned in Dunhuang, dedicating himself to copying Buddhist mural paintings in the Mogao Grottoes. To further study the origin of Buddhist art he travelled to India in 1950 and encountered the precious opportunity to study mural paintings in the Ajanta Caves for three months. Zhang’s ‘Journey to the West’, combined with his diligent practice of copying Buddhist mural paintings, to a great extent revitalized the study of China’s very early artistic engagement with India after a thousand years of stagnancy, and in turn shed new light on modern Chinese art reform. During his time in India, Zhang also created a series of portraits of Indian ladies using Buddhist figure painting techniques. (fig. 1)

Fig.1: Zhang Daqian, Indian Dancer, 2019 Sotheby’s Hong Kong.

From the perspective of many modern Chinese art reformers, Indian art did not merely represent a mono-identity exotic element, but a convergence of multicultural traditions. Merging with the art of Egypt, Greece, Persia and China, Indian art maps out a significant bloodline of succession and evolution of various art traditions and techniques thereof. Leading 20th century Chinese artists, such as Gao Jianfu, Zhang Daqian, and Xu Beihong (1895-1953), all had the experience of studying art and holding exhibitions in India. Xu Beihong, one of the most famous ‘westernizers’ in China, once encouraged his student to go to India in the quest for the real essence of art. Gao Jianfu held similar viewpoints. In his vision of the new Chinese painting, he believed that Chinese art should not only take in elements of Western art, but it should also embrace and absorb nourishments from all other cultures.

Having shared a similar experience of withstanding cultural pressure from the West in the 20th century, India inspired China not only in how to retain the confidence of Chinese culture while broadening its vision to a wider range of cultural traditions, but also in how to regard the motivation of making art. Holding compassion and caring for human beings and all living things in the highest regard, the remarkable modern Indian artist Nandalal Bose (1882-1966) considered painting to be a pure meditation on human nature. He noted that “the way of art is nothing but the way of loving things … It is out of long contact that liking for a place or a thing slowly develops.” 2 In terms of making art, Bose placed much emphasis on the ‘very beginning mind’ and solicitude rather than aesthetic tastes and techniques. One of his Chinese students, Chang Xiufeng (1915-2010), under the inspiration of Bose, painted a series of Bengali everyday life driven by a passion for ordinary things.

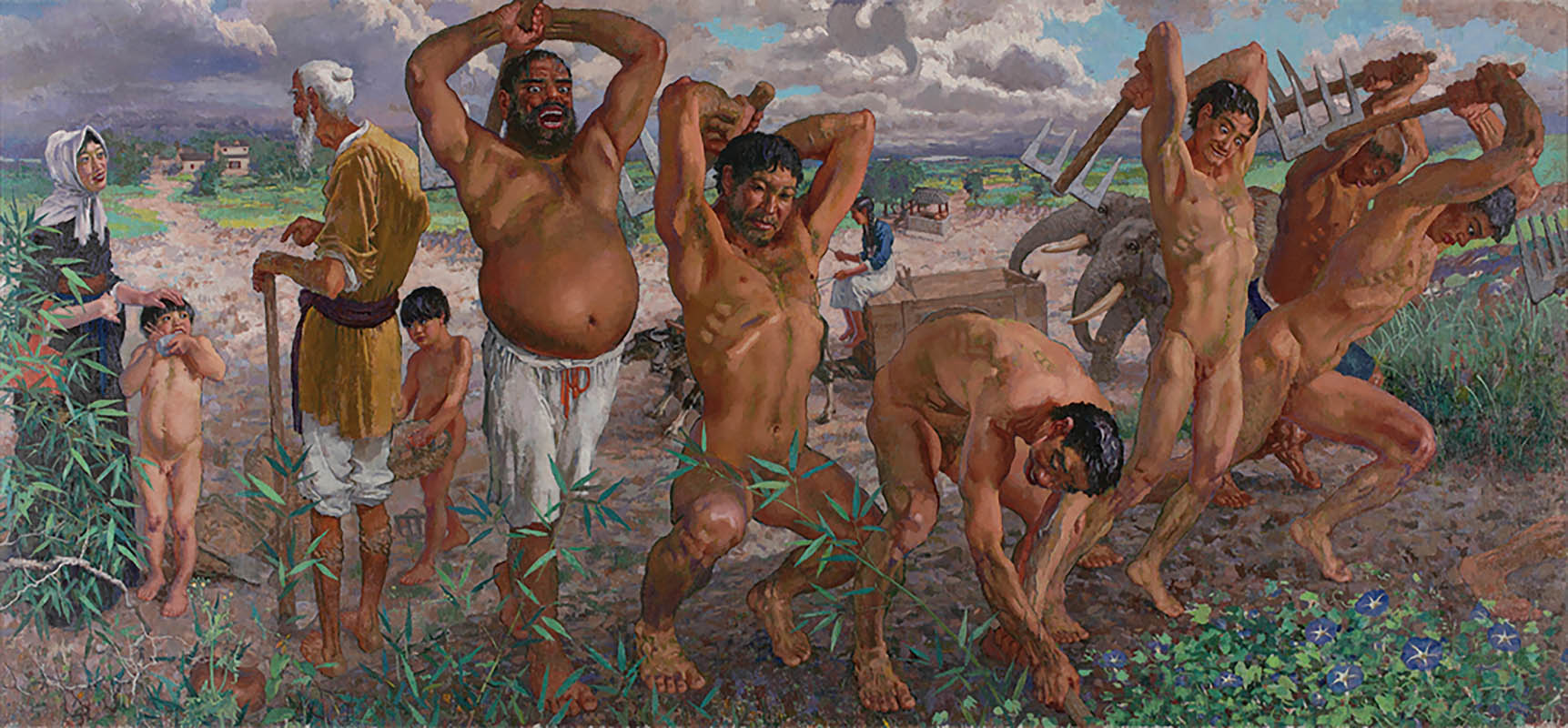

The notable modern Chinese painting The Foolish Old Man Moving the Mountain was also created out of this truehearted humanity. Its major figures – the movers of the mountains – are essentially based on Indian models. (fig. 2) Xu Beihong once explained that while making this painting in India, he was deeply touched by the local workers, not only for their magnificent physiques, but also for their uprightness in character and sincere demeanor. In the ensuing period, the attentiveness for ordinary people and everyday life situations, especially for peasants and workers, was combined tightly with revolutionary thoughts, and gradually became an undercurrent of the following wave of left-wing art.

Fig.2: Xu Beihong, The Foolish Old Man Moving the Mountain, Xu Beihong Memorial Museum, Beijing.

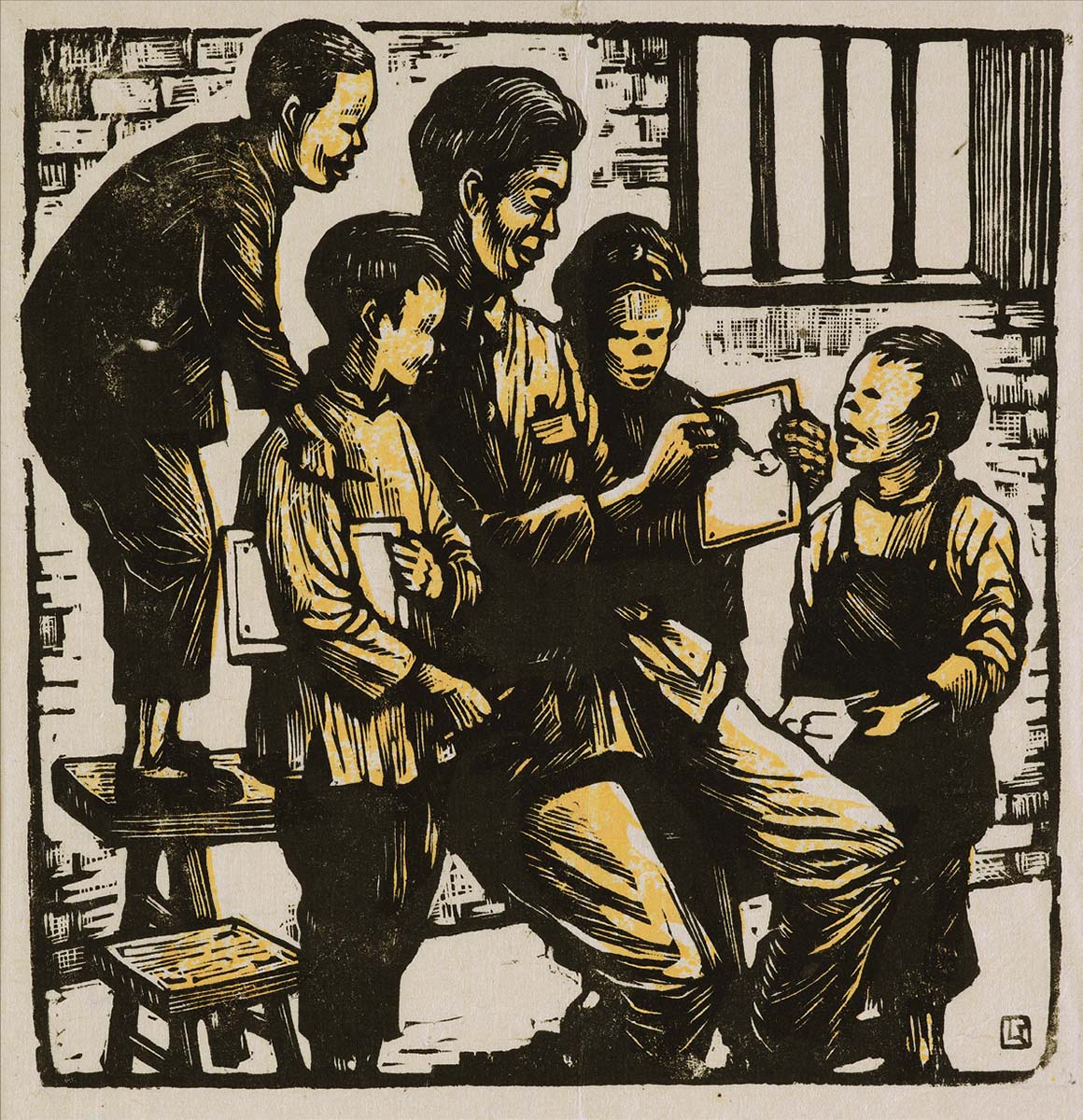

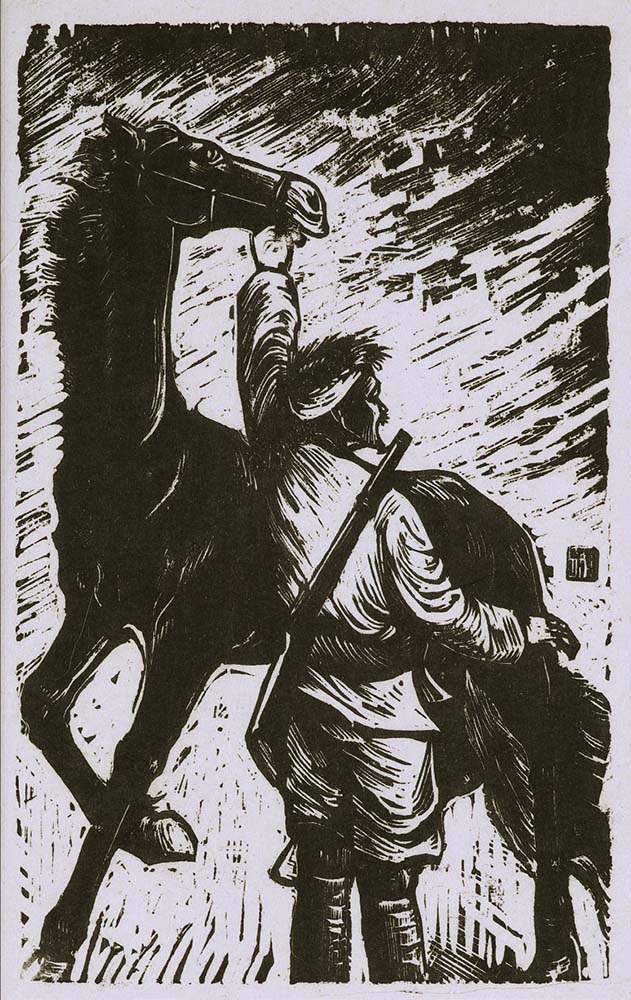

Here, we would like to pay special thanks to Professor Josh Yiu and The Chinese University of Hong Kong Art Museum, for offering us the opportunity to be the first to publish a rare set of 20th century Chinese woodblock prints that were exhibited in India during WWII. These are the precious witnesses of the ties between Chinese leftist art and an Indian audience and greatly enrich the existing knowledge about 20th century India–China artistic interactions. Lastly, we also wish to express our gratitude to Sotheby’s Hong Kong, Xu Beihong Memorial Museum, Sri Aurobindo Ashram Trust, Chang Zheng and Wang Yizhu for sharing their valuable visual materials. (figs. 3, 4 and 5)

Fig.3: Li Fu, Workers in Repair of an Airfield, Gift of Professors Patricia and Thomas Ebrey, Collection of Art Museum of The Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Fig.4: Lu Tian, A Group of Young Art Students, Gift of Professors Patricia and Thomas Ebrey, Collection of Art Museum of The Chinese University of Hong Kong

Fig.5: Xie Ziwen, Fighting Spirit (Man with horse), Gift of Professors Patricia and Thomas Ebrey, Collection of Art Museum of The Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Yu Yan, Postdoc Research Fellow at the Center for Global Asia, New York University Shanghai