Filipino family life at a distance in a digital era

In one of the many bustling spaces of the university, a petite woman, wearing cleaning gloves and an earphone, was seen cleaning windows, mopping the floor or assisting students and university staff in some other way. After several encounters in the building hallway, I eventually met her. She is Marie, a 59-year-old cleaner, who was born in the Philippines, and one of my informants during my research project in Australia on transnational family life and mobile media.

Marie moved to Australia in the late 1980s through a de-facto visa with her Australian husband. She does not have any children and had a hysterectomy. Whilst living in Australia, she has been supporting her six siblings and their families in Cagayan de Oro, Philippines. She does this through constant communication, money transfers on a monthly basis, and the occasional shipment of consumer goods. For Marie, the smartphone plays a vital role in sustaining her relationships to her left-behind family members. As she said during one of our conversations: “Of course, it is very important. I can contact them in an instant. Unlike before, when I had to write letters. When there was no mobile phones yet, it’s quite difficult to communicate at a distance.”

Marie is one of the millions of Filipinos who have embarked on an overseas journey for diverse reasons. Cross-border mobility among Filipinos is fundamental in coping with the changing demands and policies of a global economy. According to a 2019 report released by the Philippine Overseas Employment Administration (POEA), 2.5 million Filipino workers were deployed overseas in 2016. As transnational family life becomes mainstream in Philippine society, a diverse range of digital communication technologies serve as conduits for the flow of money, consumer items and expressions of affection.

According to the 2018 census released by the Australian Bureau of Statistics, there were 232,284 Philippine migrants in Australia in 2016. Historically, the first wave of Filipino migrants, who were called ‘Manilamen’, came to Western Australia and Queensland to work as pearl divers, wharf labourers, and seamen in the pearling industry.1 To date, Filipinos work across various professional and skill-based industries, such as hospitality, aged care services and education. The Filipino migrant community is in the top ten migrant communities of Australia.

A family life on the move

My research focusses on how migrant Filipinos in Melbourne, and their left-behind family members in the Philippines, use digital communication technologies to forge and maintain family life at a distance. I have examined my data through a critical mediated mobilities lens,2 emphasising how mobile devise use is engendered and undermined by the intertwining of social structures and technological infrastructures. It is through this approach that I have uncovered the emergence of communicative benefits and tensions in a transnational and digital household.

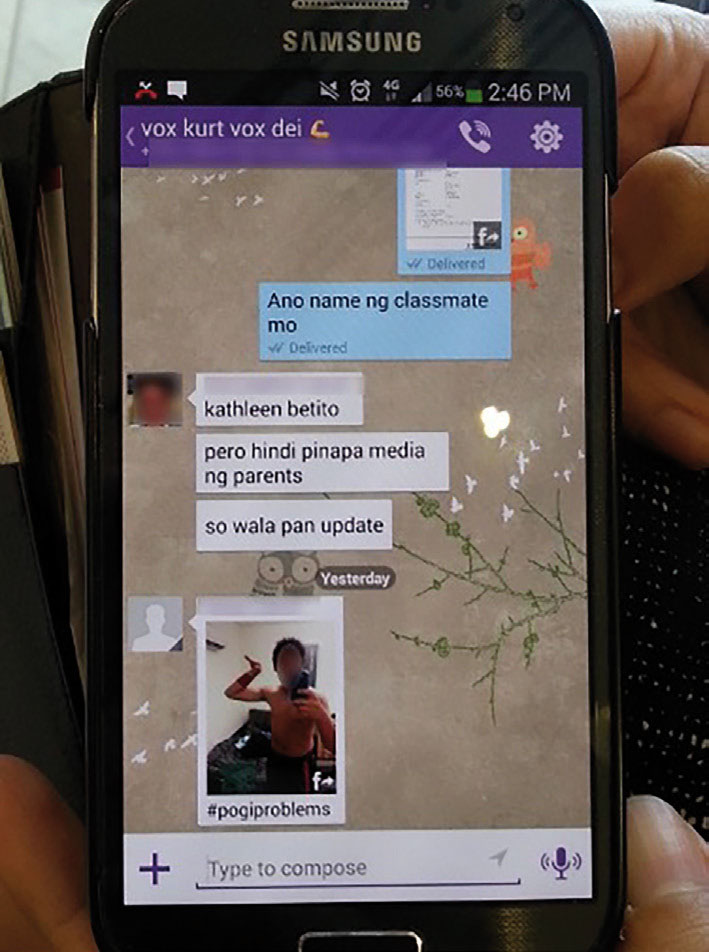

Transnational Filipino family members exchange random and creative contents through a family group chat in Viber.

Mobile device use has brought positive experiences to members of the transnational Filipino family. For instance, Rachelle, a 28-year-old sales manager in Melbourne, and her left-behind siblings in the Philippines, utilised a messaging application to exchange intimate, playful and often random texts and visuals. The constant flow of personalised content primarily contributed to making each one of them feel connected and valued.

In some cases, a social media channel and a photograph were used in the planning, coordinating and completion of a family-based business project. As I presented elsewhere,3 Cherry, a 45-year-old accountant in the Philippines, used Facebook to update her overseas husband about the making of a Jeepney, an iconic public transport in the Philippines. Cherry was taking photographs, uploading them to Facebook, and tagging the husband. It was through such practices that Cherry and her husband shared this activity.

However, both intimate connections and negative tensions can be enabled through mobile device use. As showcased in a previous publication,4 Efren, a 38-year-old chef in Melbourne, posted a photo of a newly bought pair of shoes on Facebook. This photo generated a comment from his left-behind mother, reminding him to prioritise his financial obligations back home instead of buying material items. Little did his mother know, it was his wife who bought the shoes. The lack of context of a Facebook post allowed for misinterpretation in this case. In this regard, for transnational family members, sustaining ties through networked platforms often warrants strategies. In Efren’s case, the solution was to be mindful when posting content on social media.

Overseas Filipinos and their left-behind family members often struggle with poor technological infrastructures to sustain transnational linkages. The widespread use of digital communication technologies can thus reinforce the pre-existing social inequalities in Philippine society. In a report released by Speedfest Global Index, the Philippine’s 2019 average internet speed of 19.51 Mbps was much slower than the global average of 57.91 Mbps. Nevertheless, transnational families have to manage the pains of physical separation through the use of mobile devices, money transfers and the continuous flows of care packages. In this regard, as care support becomes more family-based and networked, the Philippine government can escape from its responsibility in prioritising the social welfare of its citizens. This point is of high importance especially when the plight of Filipino migrants is symptomatic of the lack of stable job opportunities, free access to public services and provision of social welfare programs in the Philippines.

In conclusion, dispersed Filipino family members rely heavily on communication technologies to forge and maintain transnational ties. Yet, communication at a distance also comes with challenges and issues. In this vein, there is a need to further re-think the kind of support that should be given to Filipinos who serve as the lifeblood of the nation. One must start by critically reflecting upon how a digital family life can become a crucial site to critique the uneven effects of a globalising economy and thus map out ways of improving the lives of those who have been displaced and marginalised in a mobile society.

Earvin Charles Cabalquinto, Lecturer, School of Communication and Creative Arts (SCCA) at Deakin University earvin.cabalquinto@deakin.edu.au