Exploring A Design Archive of the Global Circulation of Cloth across Africa-Asia-Europe

Popular understandings of textiles and dyes are invariably colored by colonial, national, and post-war UN approaches to the development and rehabilitation of crafts since the second half of the twentieth century. More recently, the neoliberal wave has prompted the institutionalization of culturally significant textiles within national discourses of heritage and/or creative economies. On the other hand, historiographies of cloth – interrogating cultural authenticity, provenance, and patrimony – inevitably run up against histories of capitalism, colonial commerce, and global markets, and must necessarily adopt trans-regional perspectives. In this essay, we outline the parameters of a proposed research collaboration that takes an archive of pattern books as a point of departure – namely, an archive dating back to the nineteenth century and belonging to an industrial printing company in Senegal – to illuminate connected histories of textile production in West Africa, Asia, and Europe.

An Africa-Asia-Europe axis of collaboration

This project builds on discussions on transnational histories of cloth exchanges between Africa and Asia, which took place during a weeklong In Situ Graduate School (ISGS) co-organized by IIAS and Leiden Global of Leiden University, in the historic textile town of Leiden in September 2022. The immersive master class brought together a group of conveners, graduate students, local practitioners, and curators of prominent museums holding vast collections of Asian and African textiles in Leiden and Tilburg, to share their knowledge and experience from transnational, global perspectives. A public roundtable concluded the ISGS with open questions regarding archival practice and museum representations of cloth within Eurocentric historiographies. Also discussed was the erasure of local knowledge and labor from dominant discourses that emerged from the legacies of colonial collecting within the disciplines of art history, anthropology, and museum studies. Co-conveners Neelam Raina, Pedro Pombo, and Jody Benjamin are currently co-editing a volume titled Decolonising Cloth, which includes contributions from participants of the ISGS among others, under IIAS’ “Humanities Across Borders Methodologies” book series with Amsterdam University Press.

Our collaboration also builds on a recently published monograph that explores textile histories across a broad region of western Africa, from the Malian Sahel to riverine Senegal and coastal Guinea, during the eighteenth century. In The Texture of Change: Dress, Self-Fashioning and History in Western Africa, 1700-1850 (Ohio University Press, 2024), Benjamin analyzes archival, visual, oral, and material sources drawn from three continents to illuminate entanglements between African textile industries and global commerce, the politics of Islamic reform, and an encroaching European colonial power.

The pattern books housed in Senegal represent a rich, unexplored archive of printed cotton textiles manufactured in Europe for West African markets. We adopt a South-South lens to explore questions like: How did European producers learn about West African consumer tastes and preferences for printed cloths? Which Asian designs and patterns became popular in particular West African markets, and which were less taken up? Which local motifs or cultural symbols were adapted into wax print cloth for African markets? What was the impact of the then-novel use of chemical dyes on consumer tastes and on the local environment? What was the impact of importing these mass-produced colorful wax prints on local weavers and dyers, and how did they respond? How comparable are the dynamics of artisanal textile production in West Africa to those unfolding in parts of Asia at the same time?

Our goal is not only to produce a co-authored research paper, but also to develop a collaborative master’s level program for the production and dissemination of textiles histories in the Global South, which can be adapted in a variety of local contexts.

Artefacts of craft knowhow: printed textile pattern books

Our inquiry began with Pattern Books displayed at the Galerie Atiss on the occasion of the 15th edition of the Dakar Biennale of Contemporary African Art, also known as Dak’Art (November 7 – December 7, 2024). The 30 or so textile pattern books from the turn of the twentieth century are thick, dusty volumes with hundreds of printed cotton cloth samples. Containing a huge repertoire of ‘Wax Print’ designs, these volumes are part of a larger collection of technical knowhow of one of the first industrial textile printing and dyeing units in Senegal, SOTIBA Simpafrique (Société de Teinture Impression et Blanchiment Africaine), established in 1951. As SOTIBA came into existence many decades after the pattern books were created, it is not yet clear how the books became part of the company’s archive.

The story of the colonial commerce in printed textiles begins with the invention in the 1830’s of La Javanaise, a textile printing machine that could mechanically reproduce designs that were otherwise produced by hand. Dutch manufacturers and traders were quick to establish a monopoly in the production and trade of imitation, machine-made, printed textiles for the Indian and Javanese (Dutch East Indies) markets. When the reception and taste for these fake batiks, identifiable as being printed only on one side of the cloth, declined in the late nineteenth century, there was a scramble between British, Dutch, and Swiss manufacturers to find new markets in Africa. There are many different accounts by historians on how and when the designs originally intended for Indian and Indonesian markets were adapted for African consumers. One story attributes the circuit of ideas and visual references between missionaries of the Basel Mission in West Africa and the subsequent role of the Basel Trading Company (BTC) in expanding its distribution channels via the missionary network.

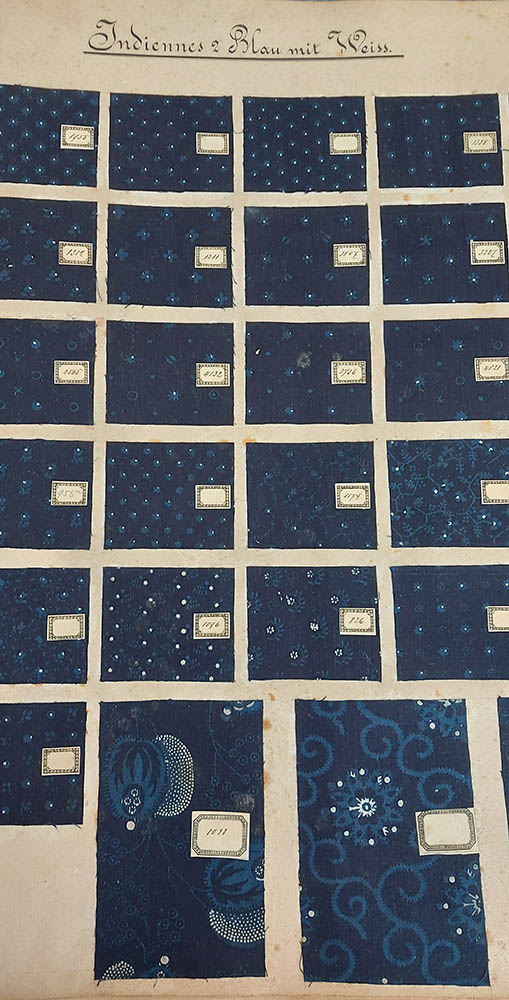

Fig. 1: Replicas of Indian Chintz patterns referred to as Indiennes. These are predominantly in indigo blues and madder reds with tiny motifs such as spots and buds (buté), tendrils or creepers (bél), checks and stripes, and overall ordered web patterns (jaal), themselves drawing from an Indo-Persian heritage. (Photo courtesy of the authors, 2024)

The sample books we encountered in Dakar are artefacts of craft knowhow and testimony of the industrial espionage between three competing European textile dye and printing companies at the turn of the twentieth century. There are three discernible design registers, indicating different consumer preferences: those for the Indian subcontinent, for the Javanese archipelago, and for West African markets. In the first category of prints are copies of Chintz patterns, or Indiennes [Fig. 1]. The second register includes patterns intended as unstitched garments like the sarong, with an identifiable border, body, and end-piece, using a magnificent range of flora, fauna, and hybrid mythical creature motifs taken from diverse cultural traditions including China. The vocabulary of motifs, colors, and layout for these two categories refers to the existing assemblage available to British and Dutch traders from professional artisan communities in their respective colonies [Fig. 2].

It is interesting to see how the repository of designs for the African market, the third register, are bolder and bigger in size, echoing references from colonial modernity such as the alphabet, the book/Bible, blackboard, the clock, ships, lighthouses, buildings, coffee beans, playing cards, and more. The color palette for the African wax prints is also more vivid, as they utilize the newly introduced chemical dyes which are in brighter hues and tones than the more subdued natural dyes derived from plants and insects, intended for Asian consumers [Figs. 3-4].

Fig. 3: Sample patterns for the African market in broader cloths with motifs drawn from colonial modernity in vivid colors. (Photo courtesy of the authors, 2024)

Fig. 4: Cylindrical roller pins, also in the SOTIBA archive and displayed at the Dakar Biennale. (Photo courtesy of the authors, 2024)

In the industrial printing technique, cylindrical roller pins, also in the SOTIBA archive and displayed at the Dakar Biennale, mechanized the hand-applied wax or the resist painting process, prior to dyeing the cloth. These roller pins were probably hand-engraved with motifs in reverse so that they would leave a positive impression on the cloth with the application of color. The motifs are predominantly drawn from banal or generic representations of ‘Africa’ and were referred to as the ‘Veritable Fancy Print’ or ‘Lagos’ [Fig. 5]. Among the rollers on display there is one that bears the image of President Senghor, who argued for a new politics of cultural representation that affirmed local and regional economic self-sufficiency. A textile panel showing this image is now in the collection of the British Museum.

Fig. 5: Among the roller print panels on display at Galerie Atiss was one produced at SOTIBA to commemorate the First World Festival of Black Arts (Festival Mondial des Arts Negres) held at Dakar in 1966. (Photo courtesy of the authors, 2024)

The ‘Wax Prints’ or ‘Javas’ are different from the ‘Fancy’; they bear an aesthetic value for an elite segment of consumers of African batik who seek a global fashion brand like Vlisco. Based in the Netherlands, Vlisco continues to hold a virtual monopoly for markets in West Africa on account of their indomitable design repertoire and technical mastery, dating back to colonial times. Yet, there is also a growing trend among social entrepreneurs and designers, in and from Africa, to valorize the handmade, fueled by a neoliberal nostalgia for a bygone era, also visible in Asia. It involves a search for design solutions in collaboration with local artisans to produce and popularize swadeshi or “one’s own” versions of wax printed textiles. It is part of an effort to reclaim cultural autonomy and national self-fashioning through textile motifs, prints, and patterns that, despite colonial roots, can connect an inalienable past to more sustainable and just futures.

Aarti Kawlra is the Academic Director of Humanities Across Borders at IIAS. Email: a.kawlra@iias.nl

Jody Benjamin is an Associate Professor of History at Howard University, USA. Email: jody.benjamin@howard.edu