Examining Northeast Asia’s Cultural Heritage on the UNESCO World Heritage List through Data

The concept of ‘World Heritage’ was conceived and developed in the West by the UNESCO Organization in 1972, and since the establishment of the official World Heritage Convention, almost all Asian countries have actively designated their national heritage as ‘World Heritage.’ In principle, ‘universalism’ is at the core of the World Heritage Convention’s concept of ‘Outstanding Universal Value (OUV).’ However, because this framework was shaped and cemented in the West, this means that Western standards were and continue to be applied to other parts of the world, including Asia. With this in mind, data analytics can be used to question whether a pattern can be found to decipher a particular ‘Asian’ characteristic or strategy in the case of the sites of Northeast Asia.

According to the World Heritage Convention, the region of ‘Asia’ is categorized under ‘Asia and the Pacific.’ As of 2021, a total of 187 cultural heritage sites were registered within the ‘Asia and the Pacific’ region. The findings from quantitative data analysis reveal that the inscription of sites located in Asia began in 1979, a year after the first set of World Heritage Sites became designated in 1978. Iran (with three Cultural Heritage Sites) and Nepal (with one Cultural Heritage Site) were the first countries to designate. With the turn of the 1980s, South Asia was responsible for pushing up the inscription rate in Asia and then, in the 1990s, Northeast Asia began to govern the fluctuation patterns of the region. From that point forward, the fluctuation patterns for site inscriptions in Northeast Asia are mirrored by the fluctuation patterns for the whole of Asia.

A total of 74 sites in Northeast Asia have been inscribed onto the World Cultural Heritage List: 37 sites in China, two sites North Korea, 19 sites in Japan, three sites in Mongolia, and 13 sites in South Korea. In order to identify how each of the countries of Northeast Asia perceive the way in which the value of their cultural heritage should be presented to the wider world, the OUV ‘Brief synthesis’ texts, ‘Criteria’ texts, ‘Integrity’ texts, and ‘Authenticity’ texts of the Cultural World Heritage Sites for each country were analyzed, with a particular focus on frequently occurring concepts.

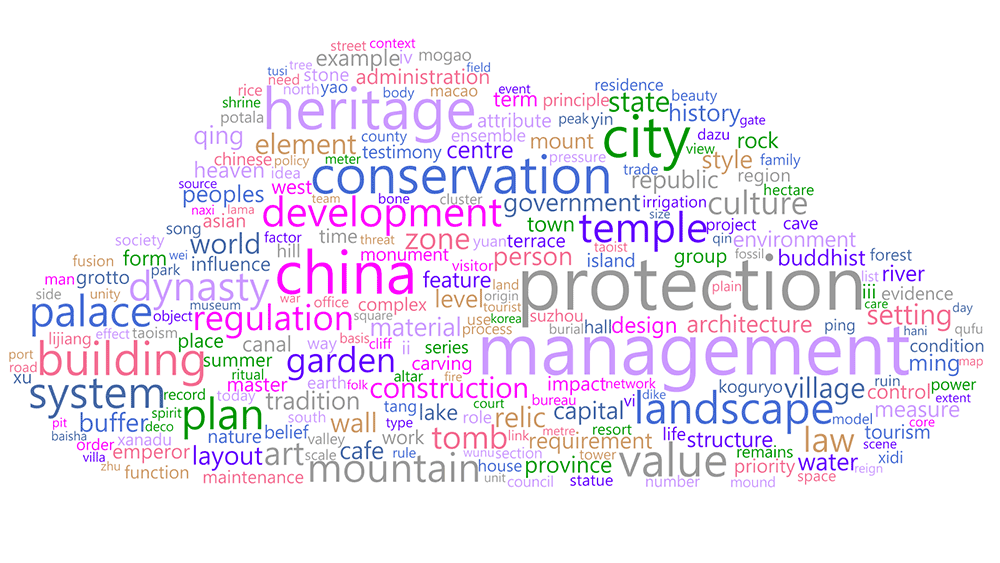

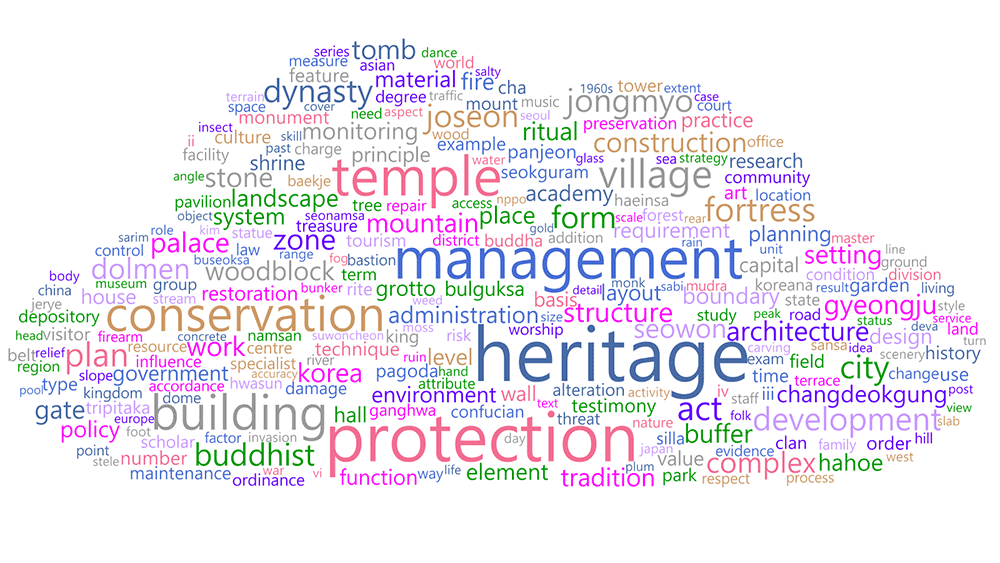

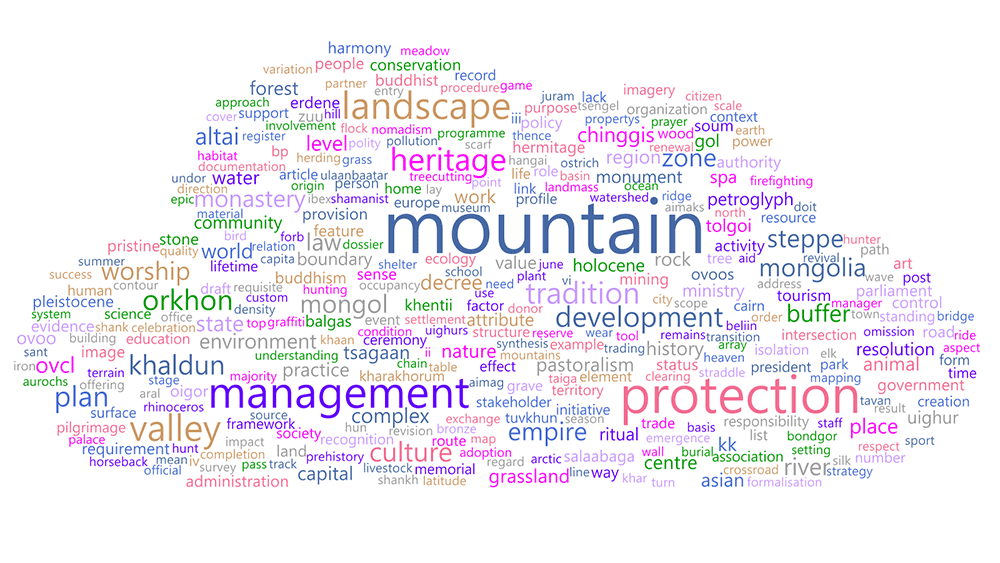

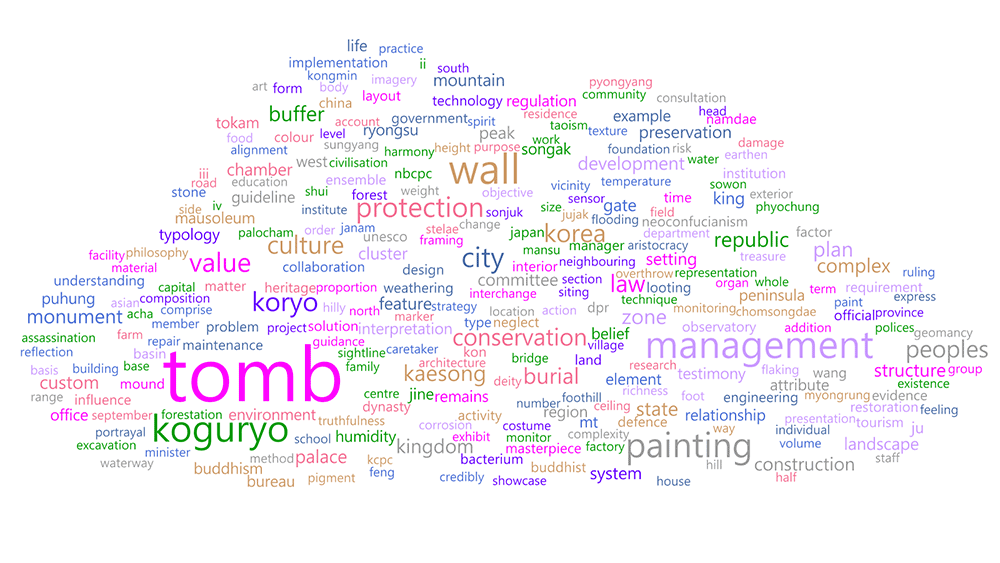

The word clouds that were produced to visualize the most frequently occurring words/concepts per country reveal some interesting patterns that provide insights into both shared and distinctive perceptions regarding Cultural World Heritage among the countries of Northeast Asia. The word clouds presented in Figures 1-5 illustrate that ‘management’ and ‘protection’ are the common key concerns; this is also the case for all of Asia, as can be seen in Figure 6.

However, some notable differences can also be observed. In the case of China and Japan, it is interesting to see that the respective country names occur with high frequency. In contrast to this, for South Korea, the country name occurs with less frequency. This may be because the South Korean strategy of site inscription was to appeal to their ‘universal’ value. The fact that ‘heritage’ occurs with particularly high frequency in the texts for South Korea – reflecting the intention to objectify the sites as (universal) heritage – is meaningful in this context, particularly given the fact that ‘heritage’ is an underused concept in the texts of Japan.

Finally, it can be observed that in the case of North Korea and Mongolia, description of the sites themselves, rather than discourse on the sites, features centrally in the official Cultural World Heritage documents. The fact that ‘mountain’ in the case of Mongolia and ‘tomb’ in the case of North Korea appear with high frequency attests to this fact.

Fig. 1: Word cloud illustrating the most frequently occurring words in the official texts related to China’s Cultural World Heritage Sites (n=37). (Figure by the authors, 2023)

Fig. 2: Word cloud illustrating the most frequently occurring words in the official texts related to South Korea’s Cultural World Heritage Sites (n=13). (Figure by the authors, 2023)

Fig. 3: Word cloud illustrating the most frequently occurring words in the official texts related to Japan’s Cultural World Heritage Sites (n=19). (Figure by the authors, 2023)

Fig. 4: Word cloud illustrating the most frequently occurring words in the official texts related to Mongolia’s Cultural World Heritage Sites (n=3). (Figure by the authors, 2023)

Fig. 5: Word cloud illustrating the most frequently occurring words in the official texts related to North Korea’s Cultural World Heritage Sites (n=2). (Figure by the authors, 2023)

Fig. 6: Word cloud illustrating the most frequently occurring words in the official texts related to all of Asia’s Cultural World Heritage Sites (n=187). (Figure by the authors, 2023)

This study used the ‘distant reading’ method of text analysis to deconstruct the discourse on Cultural World Heritage with great effect. Distant reading, a radical approach to the study of a large collection of texts that first emerged within the field of literary criticism, but which has since been used to great effect in numerous other disciplines, made the study of the large corpus of material associated with 87 sites a feasible endeavor. By adopting this method, the commonalities and differences in the heritage related discourse of the Northeast Asian countries could be identified, allowing a transition from national to regional narratives to take place. It is expected that further analyses on Asian heritage-related datasets using this approach will help bring together ‘Asian Studies,’ ‘Heritage Studies,’ and ‘Digital Humanities.’

Ilhong Ko, HK Research Professor, Seoul National University Asia Center, Regional Editor of News from Northeast Asia. Email: mahari95@snu.ac.kr

Minjae Zoh, HK Research Professor, Seoul National University Asia Center. Email: mz369@snu.ac.kr

Junyoung Park, PhD Candidate, Department of Korean History, Seoul National University. Email: zkdwlsk0111@snu.ac.kr