Establishing a Regional Framework for Migrants in Semarang

Semarang is in danger. The capital and largest city of Central Java, Indonesia, is sinking at an alarming rate: up to six or seven centimetres per year (with up to nineteen centimetres in some areas). Enthusiastic future developments are underway to reinvigorate the city, but solutions need to be found, and new frameworks developed, to properly meet this challenge. In addition, people are migrating south, where there is fresh water and less risk of flooding or landslides. Migration patterns show how the availability of fresh water plays a crucial role in Semarang’s urban-development patterns. Urbanisation needs to be guided by freshwater availability. This article outlines a development plan that addresses these issues and situates the plan in its wider regional context.

Semarang: an introduction

This study begins with a question: can a regional framework for migrants be established in Semarang? In order to answer this question, the current status of the city needs to be analysed, beginning with the population. The current population is increasing at a rate of 1.41 percent annually. Out of a total of 1.65 million people, 77,800 are considered impoverished. A large number of Semarang’s economic activities are considered “informal”, and the unemployment rate is 7.76 percent, considerably higher than the Central Java average, which is 5.86 percent. 1

Greater Semarang (Kedungsapur) has a population of close to 6 million. This population is predominantly Javanese, with a significant Chinese population. The Chinese population is the result of Chinese migration in previous centuries, with the descendants of these early migrants still living in Semarang. The city has an annual economic growth rate of 4.6 percent, and 30.38 percent of total economic activities consist of trade, restaurants, and hotels. The second biggest economic sector is the processing industry, which accounts for 27.37 percent of the economy.

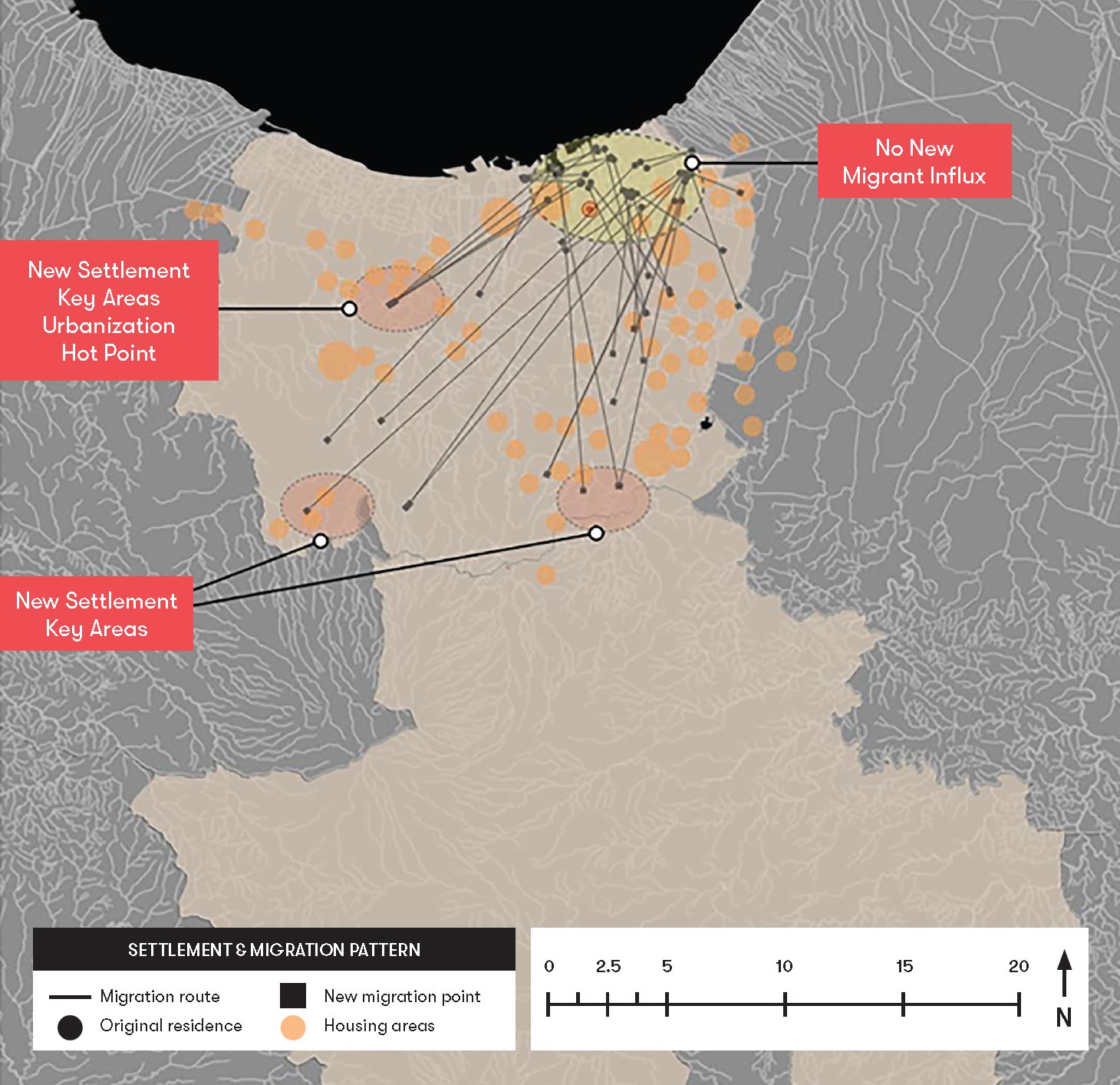

Another important issue is the migration of city residents to the hinterland. It is clear to see that people are moving out of the danger areas, mostly to places with higher elevation, fresh water supplies, and more greenery. This could indicate the kind of living environment the people deem to be “good.”

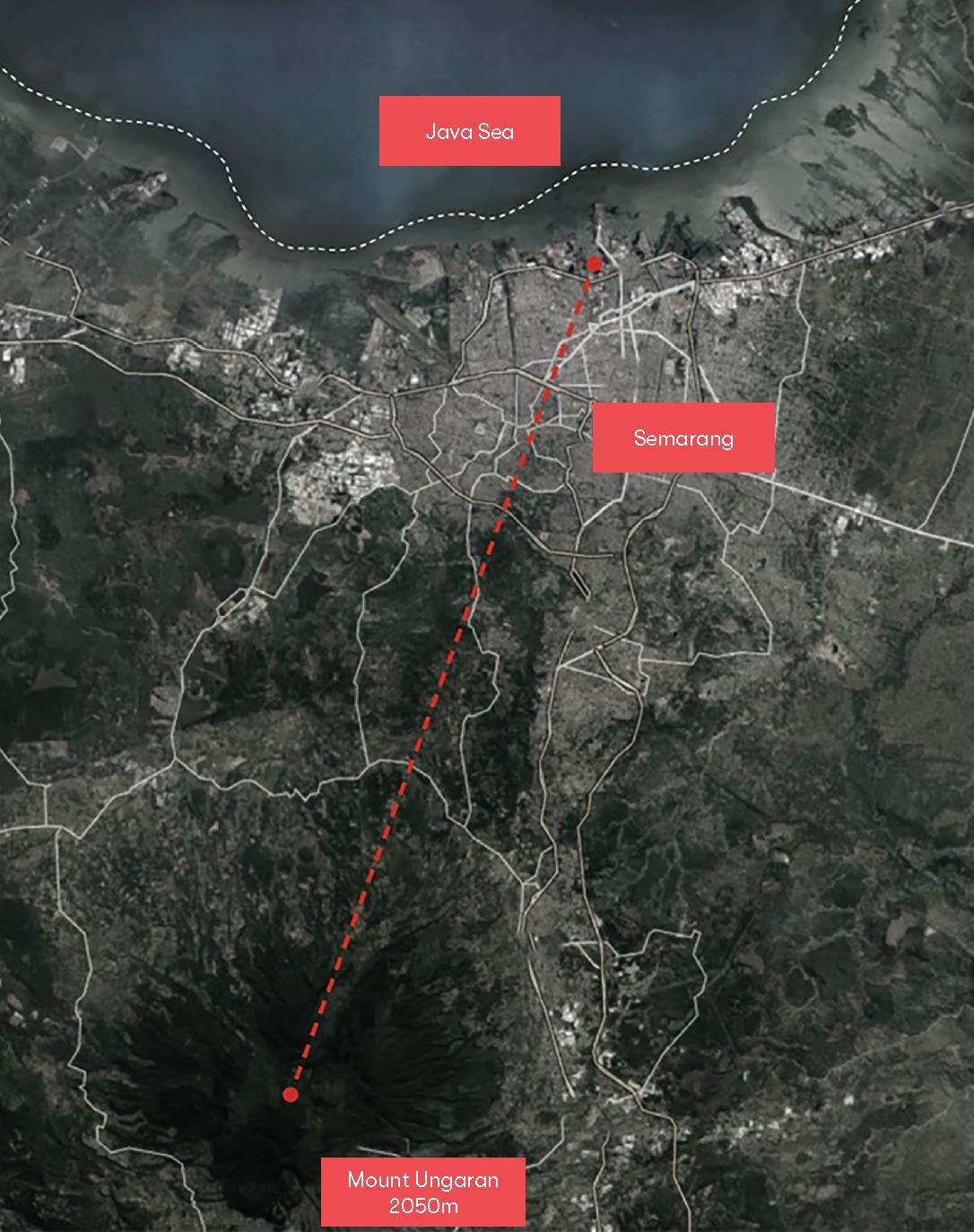

Water source depletion is another issue related to migrants and the environment. The urban landscape of Semarang is largely characterised by its water bodies. The Java Sea borders the city to the north. This coastal area used to be bordered and protected by mangrove forests, but much of the natural mangrove forests are now lost, causing even more flooding, erosion, and sedimentation in the coastal area (a problem we also see in Asmeeta Das Sharma’s paper, “Recentering Climate Migration in the Bengal Delta”). The Semarang river runs through the heart of the city. Starting at Mount Ungaran, it runs through the centre of the cityscape before debouching into the Java Sea. This river plays a crucial role in battling flash floods caused by sudden and intense rainfall when water flows from the mountainous areas into the city. However, hardening the river edges and improper maintenance have only contributed to the flooding and have hindered the ability of water to discharge effectively in the case of flash floods. To assist with these problems, two canals (to the east and west of the river) were built.

Semarang is currently being transformed into a polder system. 2 The coastal defence master plan that is currently underway consists of a large dyke structure circumscribing the urbanised region of Semarang as well as its shoreline and mangrove areas. This seawall will also serve as a highway, being an important connector for Semarang and the regional traffic between the east and west of Java. A series of pumps and water basins will drain the new polder system, although the weakest links within this vulnerable approach of coastal defence still need to be examined.

This is the reason why a regional framework for the migrants of Semarang is needed. The fact that Semarang is sinking at an alarming rate also gives this need an added urgency. The city is running out of land to develop, but the population is increasing. However, Semarang is filled with opportunities that make it an interesting site for study, and which also makes this paper’s proposed framework for migrants even more important.

Fig. 1: Settlement migration patterns (Figure by Sun Woo Kim, 2019).

The city of Semarang currently faces many natural and built infrastructural problems, yet there are more opportunities to be harnessed than dangers to be overcome if only further development can be channelled effectively. The future of Semarang is enthusiastically anticipated by locals as well as the citizens of the rest of Indonesia. The following three sections highlight some of the main reasons why Semarang’s future is potentially so bright, and why we should revive the city.

Semarang in context: history

The first factor is the city’s history. The old city of Semarang has been called the “Sleeping Beauty of South-East Asia,” and plans are underway to have the central historical district of Kota Lama declared a UNESCO World Heritage City.

Located on the north coast of Central Java, it is the largest city in this province, and the fifth largest in Indonesia. The deep, rich history of Semarang city is still “sleeping,” awaiting the moment when it will be awakened. There is great economic and cultural potential in Semarang, especially taking into consideration the Kota Lama-Semarang old town. Heritage buildings and the surrounding nature preserve areas are in danger of deterioration and damage by haphazard development and a lack of urban planning by the central government. The historical city centre and the profound natural beauty of Central Java are in continuous decline, and therefore need a structured development plan to preserve their values.

The reason Semarang has such a rich history is because it was – and still is – known as Indonesia’s gateway to the world. Its extensive port facilities act as a hub and connecting point to the world beyond the Java Sea. Thanks to this history as a trading hub and port city, Semarang has a mix of Asian and Western culture and architecture. The city’s social heritage is very rich thanks to its mixed ethnic and religious groups, making the city even more prominent than some other international port cities, such as Penang, Vigan, and Batavia, which also have similar international architectural and cultural identities. What makes Semarang unique is that it possesses a strong connection to the development of locomotives and transportation. Further railway development through high-speed trains is planned, thus making this identity even stronger, and making Semarang even more important locally and regionally.

Now that it is aiming for UNESCO World Heritage City status, more attention is being placed on the history of the city. The delegation of the Republic of Indonesia submitted its documents to have Kota Lama turned into a UNESCO World Heritage site in 2015. 3 Kota Lama has been the carrier of the political, social, and economic representations of different historical phases of human civilisation, from its diverse architecture styles to the development of the old fortified city into the international cosmopolitan city it is today. Although still on UNESCO’s tentative list, Kota Lama is the heart of Semarang, helping to enrich the city’s deep cultural identity and history. In the future, the city of Semarang will continue to strive to become a UNESCO World Heritage site, and this will help it to continue to preserve and protect its historical core of Kota Lama.

Semarang in context: ecology/geology

There is much to be considered regarding the ecology of the area. Mount Ungaran encompasses primary forests and biodiversity conservation areas which are home to many exotic species of animals. Most of the mountainous areas around Semarang have high ecological significance, this is why the mountain areas should be preserved as much as possible.

This study’s analysis of the hinterland’s volcanic activities was crucial because it has a strong bearing on the new settlements that will be made in the up-hill areas. Geothermal activity affects settlements: not only does it create tectonic movement, but hot spring activity can be harmful to people. In addition to this, up-hill activities affect land subsidence in lower areas: the whole landscape is connected, all parts to each other.

The relation between Mount Ungaran and the surrounding water landscape was also investigated [Fig. 2]. This was also a factor when examining the urban status of areas to see which were the most urbanised and which were in need of alteration. The mountain landscape seems – so far – like it is full of potential for development in the future.

Semarang in context: society

Community-level organisation in Indonesia is very tightly knit compared to some other countries. Community-based early-warning systems for disasters and their responses are well organised through self-governing systems called Rukun Tetannga (“neighbourhood association”) and Rukun Warga (“citizens’ association”). Because not every household can be reached through the government’s top-down system, the Rukun Tetannga and Rukun Warga systems are efficiently used in people’s daily lives.

Rukun Tetannga denotes a group of 18-20 households, with monthly meetings held by their leaders in order to discuss issues of everyday life that affect the community. Each Rukun Warga, on the other hand, consists of 7-15 Rukun Tetanngas. The heads of each Rukun Tetannga gather every two to three months to gather opinions and suggestions on administrative issues that they then deliver to higher administrative levels. Finally, 10-15 Rukun Wargas are considered as one sub-district of an administrative area.

Fig. 2: Movement to the south (Figure by Sun Woo Kim, 2019).

Community-level coordination is very well organised in Semarang. However, there is a big segregation between the government level of urban planning and local development. Large areas of the city – both urban and rural alike – are unregulated, and much of the local development and reform is conducted on the community level. However, this problem also makes community organisation even stronger. The government is now striving to make the bottom-up structure more closely connected to its own top-down way of doing things, which would bridge the current gap between uncontrolled development and policy regulation.

The proposed plan

The design masterplan aims at building a detailed framework for the future of Semarang. In this scenario, the coastal and mountain areas are deemed unsuitable for settlement due to the risk of flooding, subsidence, and landslides. The chosen site is in suburban Semarang (where residents from dangerous coastal areas have already migrated). Measures will have to be taken to not only encompass the new influx of residents, but also to keep the natural qualities of the area intact, especially the aquifers and watersheds. This is why detailed design areas were chosen to explore the possibilities of increasing green and blue areas (urban planning’s shorthand for non-urban land and water, respectively) in an urban context, as well as to preserve natural qualities in mountainous areas and create new areas for residents’ convenience.

The chosen intervention site is in the south of Semarang city, bordered by Mount Ungaran to the east. This area is within the administrative boundary of Banyumaik and covers the Rukun Tetannga areas of Srondol Wetan, Srondol Kulon, and Pedalangan. There is the mountain peak of Gunung Selekor east of the design intervention area. The natural qualities of this area are relatively well preserved, for little development has yet been made in this area. The Kaligarang river runs along on the border of the administrative boundaries of Banyumanik and Sekaran. This river is part of the biggest water-supply route in this area, and thus must be more vigorously protected.

When it comes to the area’s history, there has never been a master plan to guide large-scale settlement and public facilities’ development. Much of the economic development came from the switch from manufacturing to business, with local people’s housing replaced by luxury hotels and shopping malls in the city centre. The long-term residents of the area are slowly being pushed out of the city and into the outskirts of Semarang. Due to this, old villages such as Basahan, Jayenggaten, Morojayan, Petroos, Mijen, Sekayu, and others on Pandanaran Road at the centre of Semarang city are disappearing.

If allowed to continue unabated, this would have increasingly detrimental effects on the conservation of the heritage of Semarang. If the pattern of migrants being pushed to the outskirts continues, it could trigger more and even faster disturbances to the historical heritage sites of Semarang. This problem would be compounded if there are no clear guidelines on how to deal with these places once the locals have been forced to leave.

Furthermore, real estate developers construct new infrastructure, such as roads, water pipes, electricity cables, phone masts, and health and education facilities in the new areas they develop. These facilities are usually accessible to people in adjacent communities, thus making these development areas preferable zones for migrant destinations. The small- and large-scale housing developments and equivalent facilities’ development carried out in the Pedurungan and Genuk districts 4 are examples. Such development has “triggered collateral development in the surrounding regions.” 5 Thus, large-scale developers play a crucial role in triggering regional transformation. 6 However, these areas are usually the least urbanised, as well as being the natural areas that people prefer to live in on the peripheries of the city. Therefore, without a clear strategy and master plan to guide the further expanding cityscape, it will be only a matter of time until the damage done to the environment and the city’s natural context are at a point of no return.

Fig. 3: Rukun Tetannga and Rukun Warga community illustration (Figure by Sun Woo Kim, 2019).

By creating a regional framework for the migrants it will be possible to guide settlement and public facility development more easily. People will be able to choose the areas they want to move into based on living quality or their environment preferences. With regard to ecology and geology we can see that the plan’s intervention site is located in the highlands and its development is centred around areas which are relatively less steep and, hence, have less danger from landslides. The landslide danger areas, and the tectonic movement of the mountainous areas, had to be mapped in order to figure out the preferable areas for development of this project. The analysis of the hinterland’s volcanic activity was crucial because it relates to the new settlements that will be established in the up-hill areas.

Geothermal activities affect settlements because they create tectonic movements and hot-spring activities which are potentially harmful for people living near them. Also, up-hill activities affect the land subsidence of low-hill areas: as was highlighted above, the whole of the landscape is connected. There is also much to be considered regarding the ecology of the area. As we have seen, Mount Ungaran encompasses primary forests and biodiversity conservation areas which are home to many exotic species of animals. Most of the mountainous areas around Semarang have high ecological significance. This is why the mountain areas should be preserved as much as possible.

By creating migration guidelines for ecological preservation areas in the hinterlands, the plan will ensure the possibility of keeping the area’s natural qualities intact. The plan also consists of detailed guidelines (as well as a large-scale design) to try and address the needs of the new migrants in finding areas to live where they can feel safe from natural disasters, it also makes use of analysis to earmark places most suitable for new settlement, and also indicates which areas need to be protected for future generations because of their ecological and environmental importance. Finally, the plan also allows for (and actually encourages) participation from local groups to ensure there is a balance when trying to achieve this future vision so that everyone’s needs can be addressed. In terms of society, we have already seen how Semarang residents are keen to move to areas less prone to flooding and subsidence, but because of this migratory pattern the natural environment in Mount Ungaran is in danger of losing the very ecological values that make it so attractive, and this is something the plan seeks to address, with a long-term strategy to balance the needs of the new residents, without unduly damaging the qualities of the area they are moving to.

In order to achieve this, however, the plan’s design could be seen in some quarters as being controversial. Particularly the tight-knit Rukun Tetannga-Rukun Warga structure of communities and the top-down system of the government would be the biggest obstacles to making the radical changes in this proposal, so this is why the plan seeks to get their involvement and give them a meaningful say in what gets done. Furthermore, for a country with a rapidly growing population and economy, reserving land for nature preservation may even arouse opposition. However, this masterplan highlights nothing more nor less than the sort of utilitarian choices we will have to make in order to keep the environment intact for future generations. By creating a framework to incorporate the whole of the communities’ structures, it will be possible to keep them tight-knit, even if large-scale migration still needs to happen.

Conclusion

Semarang is going through rapid urban and regional transformation. This has been seen in the past and continues to the present day. However, rapid urban sprawl and developments in commercial activity are still running parallel to spatial organisation. This will cause further trouble for migrants in the future when they are looking for new areas to settle in. With the assistance of this plan’s regional framework to guide urban development, and the settlement of future migrants, it will be possible to create safer living environments for those who wish to find new abodes. 7

Sun Woo (Cassie) Kim, Urban Design Division, Haeahn Architecture, Seoul, South Korea, sw.kim3@haeahn.com