The Endangered Archives Programme. Towards a different kind of collection

We live in a world of incredible cultural diversity, which over the last century has been increasingly threatened by global capitalism. In many countries a response to this has emerged in a growing nationalism, an assertion of local, specific culture. But this is an equal threat to the diversity of voices, stories and ways of being that make up every culture. And if we cannot preserve these stories, these alternative ways of being, we will be poorer, subject to the flattening out that is the end result of both globalisation and nationalism.

The Endangered Archives Programme

There is no easy solution to this, and some would argue that change and development are inevitable. No doubt they are, but remembering is also what makes us human. And a rich memory gives us more ways of thinking about our future as well. This is the belief and motivation behind the Endangered Archives Programme, which was established by Lisbet Rausing (Arcadia Fund) in 2004. She summarised the aims of the programme thus:

“The Endangered Archives Programme captures forgotten and still not written histories, often suppressed or marginalised. It gives voice to the voiceless: it opens a dialogue with global humanity’s multiple pasts. It is a library of history still waiting to be written.”

The Endangered Archives Programme (EAP for short) is dedicated to the digitisation of any kind of archive that is at risk of being lost forever. This includes manuscripts, documents, photographs, sound recordings, newspapers and magazines. A huge variety of material has been digitised under the programme, from ancient Arabic manuscripts to photographs of the everyday life of Buddhist monks in Laos. How does this work?1

EAP749/12/1/1 - An old wooden statue of Tangtong Gyalpo. Tangtong Gyalpo’s face and body have been recently repainted golden, his hair black. The statue was cleaned and painted in bright colours prior to the 1996 Kalachakra initiation at Tabo monastery. The statue was blessed and consecrated by His Holiness the Dalai Lama at that event. On the reverse of the statue a strip of yellow cloth covers the space inside the statue that contains written prayers. The statue is unclothed. Approx 350 mm high. The material is owned by Jigmed Thakpa and has been handed down through several generations. All the materials in the archive are kept within the prayer room of the house.

Individuals or teams propose projects to EAP for funding, and if successful, work wherever the archives are located, to survey and digitise them. The archives are not taken away, and the digitised images or recordings stay in the country where the archives are found. Copies are sent to the British Library, the home of the EAP, and these are shared on the programme's website (eap.bl.uk). Over seven million images and recordings are now available on the website, a massive and diverse digital collection crossing multiple regions and fields of study. These collections are only made available with the consent of their custodians, for research and greater understanding, and not for commercial gain.

A holistic picture of a tradition

Many of the major museum and library collections in Europe are the direct result of the collecting activities of colonial explorers, soldiers and administrators. As such, these collections represent the interests and prejudices of these people, rather than the values and practices of the original custodians of the material. This has directly affected how generations of scholars have conceptualised the cultures that they study. In Buddhist traditions, for example, the study of manuscripts has favoured canonical textual traditions with their roots in India, or the works of well-known individuals. The way that these manuscripts formed part of personal or monastic collections has largely been ignored.

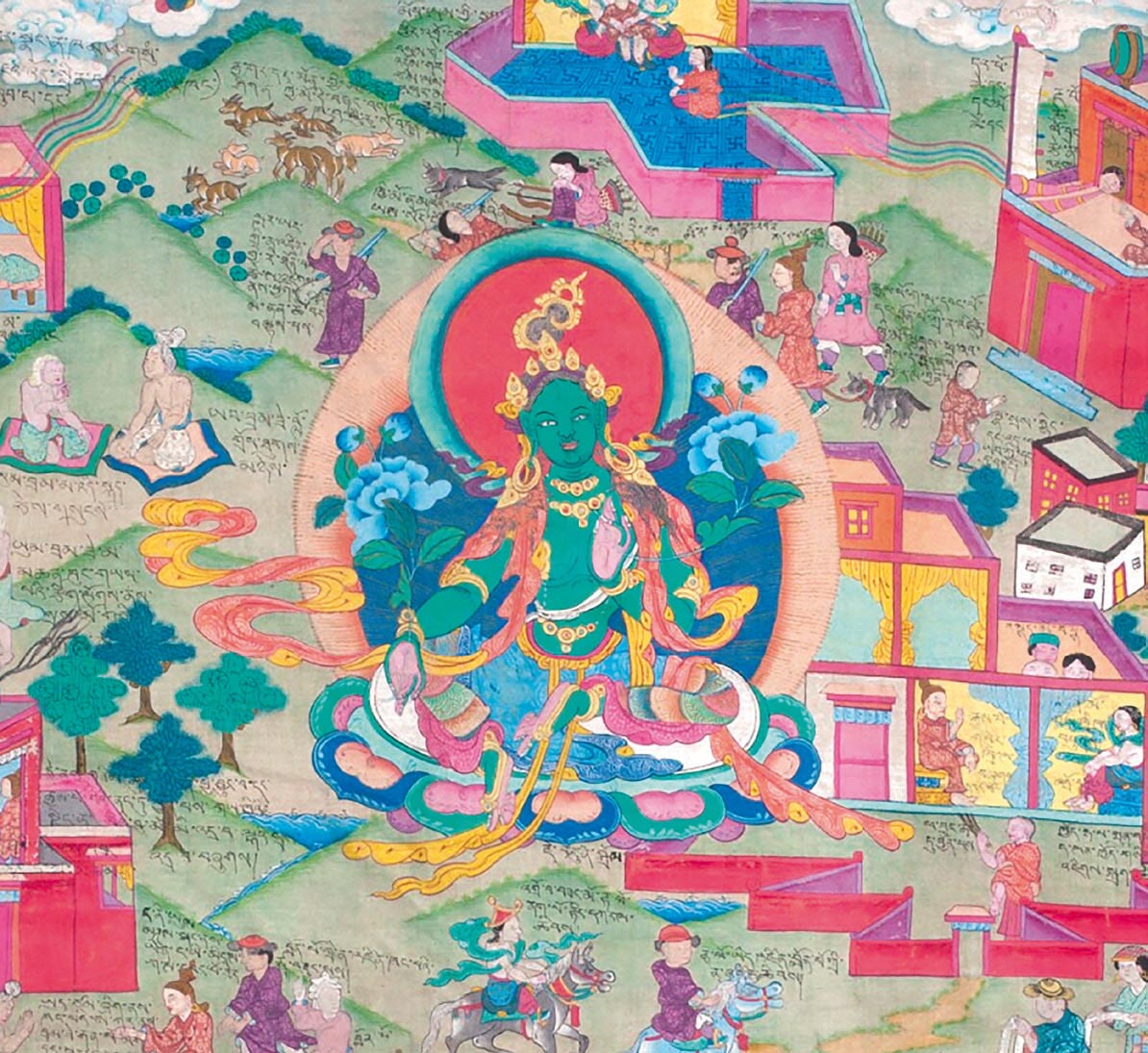

In two projects funded by EAP between 2012 and 2016, Patrick Sutherland surveyed and photographed the collections of a group of Buddhist ritual specialists called Buchen.2 Living in the Pin and Spiti valleys of Himachal Pradesh, India, the Buchen are a class of Buddhist ritual practitioners and storytellers whose traditions are now under threat. Recognising this, several Buchen families worked together with Sutherland to document their manuscripts, paintings, and other religious objects. The Buchen consider themselves to be the spiritual descendants of the 15th century saint Tangtong Gyalpo, a visionary adept in meditation who is also thought to have designed and constructed over fifty iron suspension bridges in Tibet, and to have invented the Tibetan tradition of opera known as Ache Lhamo. It is this latter achievement that links him to the Buchen, who use art and performance to communicate the essentials of Buddhist teaching: the round of rebirth and the role of karma.

The collection of a single Buchen comprises manuscripts in the Tibetan loose leaf form known as pecha, containing both ritual texts and stories to be used in performance. Alongside these are thangka paintings, used to illustrate Buddhist principles, musical instruments such as the kogpo, a six stringed wooden instrument, and statues of the Buchens' patron saint Tangtong Gyalpo. The ritual accoutrements of a Tibetan Buddhist practitioner are also present, including the metal vajra and bell, the rosary, amulet boxes and ritual daggers, swords and bows. Thus the Buchens' collections offer a holistic picture of their tradition, based on the logic of their own practice, rather than the categories of European museum and library collections.

The custodians

The Kathmandu Valley is one of the culturally richest regions in the world. It has also been the site of massive urban development in recent decades, and was hit by a tragically destructive earthquake in 2015. In the medieval period, the valley was a hub connecting the Buddhist cultures of India and Tibet, and home to renowned experts in the Vajrayana, the texts and practices of tantric Buddhism. These teachings have been passed down through the centuries in family lineages of Vajrayana teachers known as vajracharyas. These families hold rich collections of manuscripts, which are now under threat from the forces of modernisation and environmental catastrophes.

A narrative thangka illustrating the story of Drowa Zangmo. Early 21st century. New Thangka commissioned from Sonam Angdui in Kaza. The material is owned by Meme Gatuk Tenzing and has been handed down through several generations of head Buchen. All the materials in the archive are kept within the prayer room of the house. Image (Melong) size 790 x 555 mm. Full mounted size 1365 x 900 mm.

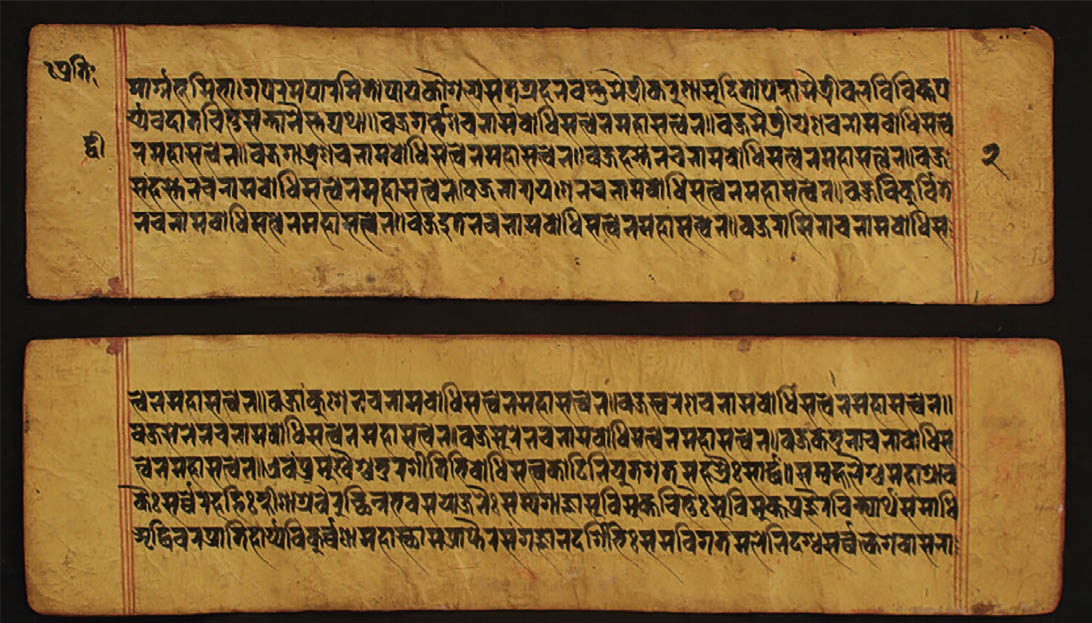

In 2013, Shanker Thapa, of Tribhuvan University in Kathmandu, started an EAP-funded project to identify and photograph the manuscript collections of vajracharya families.3 Reaching out to Buddhist families in Kathmandu and Patan, Thapa found that many were concerned about preserving their traditions, and keen to have their fragile manuscripts digitised for posterity. As with other EAP projects, these manuscripts were catalogued as family archives rather than separated by external categories such as genre or format. Thus the manuscript holdings of these Buddhist families were recorded in a way that allows us to understand much better what the texts meant to them.

In the nineteenth century, British colonial officials in Kathmandu, such as Brian Hodgson, collected Sanskrit manuscripts or had manuscripts copied especially for them by local Buddhists. These manuscripts are now in the university libraries of Oxford and Cambridge, the British Library, and the Royal Asiatic Society. They are vital sources for understanding Buddhism, in many cases containing the earliest Sanskrit versions of key Buddhist texts. Yet their original context is hard to establish; which families owned them, were they still in use, how were they acquired? Moreover, the choice of manuscripts reflects the British collector’s own interests in reconstructing the history of Buddhism, rather than recording the collections of contemporary practitioners.

EAP790/2/15 - Manuscript containing the Sutra of Five Protectors, from the collection of Suprasanna Vajracharya.

The digital collections created by Shanker Thapa with the support of vajracharya families are different: here we see the logical structure of family collections, and we can understand the part the manuscripts play in their own practices, and their relationship with those who rely on them for rituals. Thus in a single collection we see, for example, prayers to Buddhist deities, along with mantras to be chanted for a long life, astrological texts for divination, and tantric texts for the accomplishment of enlightenment. There are fewer of the famous Buddhist canonical texts than in Hodgson's collections, and this reflects which texts were (and still are) actually used in the Kathmandu Valley. This gives us a different perspective, one more closely aligned to that of the custodians of the manuscripts themselves.

Supporting the collections

The Endangered Archive Programme continues to give grants to applicants on an annual basis with a call going out every September (eap.bl.uk/grants). For those interested in exploring the digital collections, they are freely available on the programme's website (eap.bl.uk/search/site). These collections are held in trust for the original owners and their descendants, and offer the potential for an approach to research based on a greater understanding of the custodians of the traditions, who have preserved and transmitted them through to the present day.

Sam van Schaik, Head of the Endangered Archives Programme, The British Library . endangeredarchives@bl.uk