Empire at leisure. Nineteenth-century Bay of Bengal as a space of trans-colonial recreation

Historians have long appreciated the importance of bodies of water, from Fernand Braudel’s seminal work on the Mediterranean to the more recent trend in oceanic histories, whether Atlantic, Indian or Pacific. In that intellectual lineage, the Bay of Bengal is long overdue its moment in the spotlight. One fascinating and thus far under-researched facet of the region’s long history of diverse mobilities can be found in its central role in the development of imperial ideas of leisure over the course of the nineteenth century. It was a period that saw the emergence of a culture of trans-colonial recreational travel that continues to shape tourist discourse and practices in the area to this day.

The promise and suitability of global and transnational approaches to the history of the Bay of Bengal has recently been demonstrated by the influential work of Sunil Amrith. In an evocative passage of his magisterial Crossing the Bay of Bengal, Amrith instructs us to consider the diversity of the region’s histories:

“Picture the Bay of Bengal as an expanse of tropical water, still and blue in the calm of the January winter or raging and turbid with silt at the peak of the summer rains. Picture it in two dimensions on a map, overlaid with a web of shipping channels and telegraph cables and inscribed with lines of distance. Now imagine the sea as a mental map; as a family tree of cousins, uncles, sisters, sons connected by letters and journeys and stories … There are many ways of envisaging the Bay of Bengal as a place with a history – one as rich and complex as the history of any national territory.”1

What Amrith is suggesting here is that the Bay of Bengal, like any comparable area of cross-cultural engagement and interaction, is and always has been a space with a range of meanings attached to it, playing diverse roles in the lives of various actors. My work, though in many ways very different from Amrith’s, deals with a few of these imaginaries and associations connected to the region, specifically in the (trans)imperial imagination of the British and the Dutch around the middle of the nineteenth century.

I do not generally consider myself a historian of the Bay of Bengal, but my work on (trans)colonial travel in and between British Ceylon and the Straits Settlements (Singapore, Malacca and Penang) and the Dutch East Indies obviously draws attention to the mobility and interconnectedness that have historically defined the area and its immediate surroundings. In the 1840s, the starting point of my research, steam-powered shipping created regular, fast and reliable connections throughout the triangle enclosing the Bay, with Ceylon’s Point de Galle as one of its points, Calcutta as another and Penang and Singapore on the Malay peninsula as the third. Moreover, Dutch navy steamers soon latched on to this new circulation by establishing a monthly connection between Singapore and Batavia. These connections were of crucial importance to mail delivery and cargo shipments, but were also used by passengers. Amrith, in his work on regional migrations, has studied the better part of those flows; but among those passengers, occupied with rather different conceptions of travel, were also British officials based in India and touring the region on leave, as well as their Dutch counterparts taking advantage of the leisure of brief stays in Singapore or Galle for brief excursions or a spot of sightseeing. In doing so, and borrowing freely from the culture of tourism that was flourishing at the time in Europe – from the Alps to the Rhine and to the British Lake District – these travellers created a kind of colonial proto-tourism with the Bay of Bengal at its heart.

Invalid travellers and health resorts

Perhaps the most recognisable kind of travel undertaken by these people was the phenomenon of so-called ‘invalid travel’: leisurely travel for the purpose of convalescence in what were deemed to be healthier climates. There is some evidence of this sort of travel forming the basis of, if not quite a tourist industry, then certainly a kind of competitive regional market for travellers, where profits could be made. A contemporary piece in the Journal of the Indian Archipelago, titled “Advice to invalids resorting to Singapore”, laid out recommendations for officials based in India looking for a change of scenery, including tips on the best hotels, on what to eat, on where to go for excursions and, notably, on the top sights or, in the language of the day, ‘lions’ of the city – the Chinese temples of Telok Ayer Street get a special mention.2 In both style and content, the piece is not too dissimilar from a modern tourist guide.

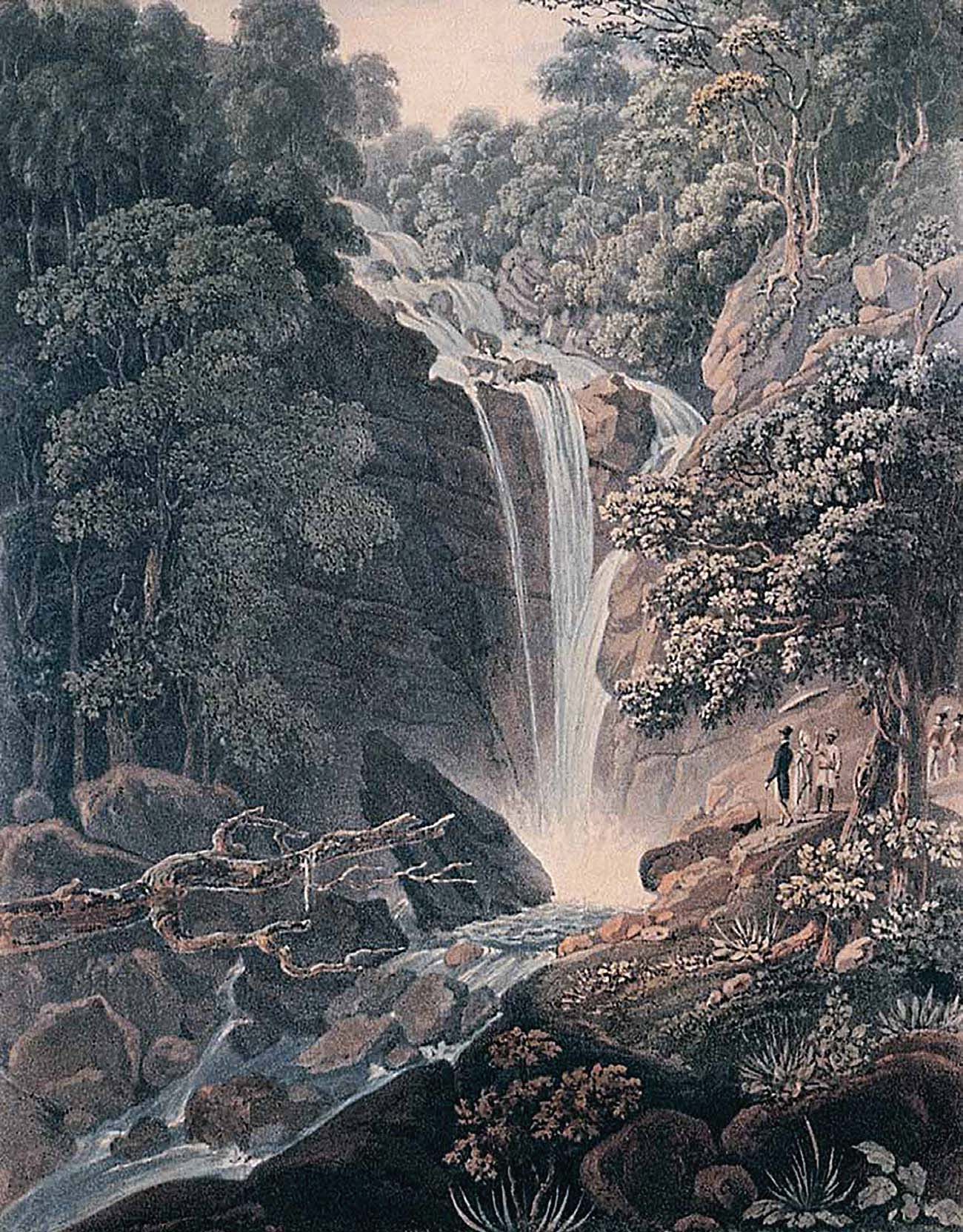

The waterfall on Penang Island, 1818. One major attraction for travellers making a circuit around the Bay of Bengal.

While seasonal travel to the hill stations of India, a practice that long predates European colonisation, has been extensively studied, it is less known that this kind of health tourism also had a fundamentally regional aspect, involving travel across the Bay and the boundaries of individual colonies. Officials from Calcutta, and further inland, would cross over not only to Singapore but also to Penang, with its famous waterfall already a noted attraction in the 1850s. The Singapore Free Press wrote in August 1845, just ten days after the arrival of the first P&O steamer in the city, about the “large number of Strangers, many of them Invalids, which we may shortly expect to see the various monthly Steamers bringing to our Island”.3 Similarly, just a year later, the Colombo-based Monthly Examiner reported on a health resort being set up in Nuwara Eliya, Ceylon, with the rejoinder that “we may yet hope to see Nuwera Ellia [sic] become a favourite place of resort for the invalids of the Presidencies [of India]”.4 Moreover, many would continue their tour beyond the confines of the British Empire to Java, then under Dutch rule. One example is Charles Walter Kinloch, who explicitly positioned his 1853 travel book De Zieke Reiziger, as a guide for aspiring tourists, suggesting in his preface that “…in the absence of any work whatever of the nature of a Hand Book relative to the Straits and Java, even the crude notes of ‘De Zieke Reiziger’ or the Invalid Traveller, would not be without their use, particularly at the present time, when through the arrangements lately concluded with the Peninsular and Oriental Company, the chief port of Java has been brought within twelve days sailing distance of the Hooghly.”5

It is apparent that travel across the Bay of Bengal, in all directions, was becoming rather fashionable at the time; its popularity can be inferred from the way that Kinloch casually mentions running into two of his “Indian friends” in Buitenzorg (Bogor) on Java, without registering so much as a hint of surprise.6 Indeed, Buitenzorg was a favoured destination not only for the Dutch elites of Batavia, but for an international body of visitors. Among its attractions were, in addition to a salubrious climate, the expansive and widely admired botanical gardens that provided an aesthetically pleasing backdrop for a pleasant stroll, and the dinner parties of the beau monde of colonial Java.

The imperial imagination

The popularity of this sort of travel had various consequences for the Bay of Bengal in the imperial imagination. The act of travelling is inevitably bound up with the creation of narratives. Travellers do this, for example, by picking out and visiting symbolic locations within a space that, over time, come to stand for something greater and more general. In the case of this kind of colonial proto-tourism, such sights were often selected to suggest something about the entangled histories of empire and colonisation. To give just two examples of such symbolically loaded sites/sights, there is the memorial to Olivia Devenish, the wife of Stamford Raffles, a reproduction of which can still be found in the Bogor botanical garden – a monument that was mentioned without fail by British visitors to Buitenzorg not so much because of its aesthetic or sentimental value but as a way to connect the space of the Dutch colony to the British historical experience: to make a story. Similarly, and for the same reasons, Dutch visitors to Ceylon liked to mention the VOC emblem on the gate of Fort Galle, even if they only stopped at Galle for a day or two on their way back to Europe.

The prevalence of these kinds of sites in the emerging imagery of colonial travel, and in published travel writing, also meant that other, local and/or Asian stories were simultaneously being pushed out of the picture. The cosmopolitan story of an Anglo-Dutch Bay of Bengal, packaged in a nicely touristic, entertaining narrative, was also an exclusive story of a European Bay of Bengal. In that narrative, as exemplified by early guidebooks like the Bradshaw’s Over-Land Guide to India (1858), Asian cities such as Madras were presented side by side with popular European destinations such as Florence, with the same sets of instructions and tips, while the local cultural and environmental specificity of each was smoothed out under the unstoppable advance of a globalising tourist discourse. In this way, early tourism had the same distancing and decontextualising effect on imperial culture as did the colonial sciences that have been well studied by historians, and that emerged at roughly the same point in time.

The Bay of Bengal came to be incorporated in a global imagery of touristic travel over the course of the middle decades of the nineteenth century. This imagery was cosmopolitan and cross-cultural but only in a tightly defined, European sense, and it served to erase a range of Asian agencies and presences from European travellers’ conception of the region, and helped obscure the violent underpinnings of colonial society. This despite the fact that this culture of travel and its attendant practices were also, in turn, adopted and adapted by elite and middle-class Asians across the region as a veritable tourist industry began to emerge towards the end of the century. Of course, tourism still continues today, in ever more overpowering and homogenising guises, around the Bay of Bengal as well as globally, and it is therefore all the more crucial that its roots in a set of deeply exclusionary colonial practices and power structures should not be forgotten.

Mikko Toivanen, European University Institute