Deregulation policy and gentrification in Chuo Ward, Tokyo

Between the 1980s and early 1990s, when land values in Japan soared, numerous plots of land near Central Business Districts (CBDs) were bought up as investments, and former tenants were displaced. The period also saw financial institutions such as banks and insurance companies moving into the Tokyo core. Industrial restructuring significantly increased the number of white-collar workers in Tokyo. In an attempt to recover its population, the local government of the Chuo ward in central Tokyo implemented a new initiative, known as the Housing Linkage Program, for large developments in 1985.

The Chuo ward government set two standards for the Housing Linkage Program according to the zoning. In the case of commercial zoning, developers were required to supply housing whose total size should be 50% or more of the project site, otherwise be extended beyond 100% of the project site. The floor space of each housing unit supplied by the Housing Linkage Program had to measure 40 square metres or larger. One problem with the Housing Linkage Program, however, was the rising cost of private housing, which resulted in a shortage of affordable housing.

With the collapse of Japan's economic bubble, reconstruction plans were abandoned. Land values continued to drop during the ensuing economic slump, which lead to high mortgage arrears rates and indebtedness. Because numerous underused plots of land stood close to Tokyo’s CBD, revitalising these areas became the government’s primary objective. In the late 1990s, price deflation drove Japan’s economy into a recession. Many small and medium-sized factories in inner Tokyo closed down or moved to other regions or abroad.

In 2002, Japan’s government introduced the Urban Regeneration Policy with a budget of 2.5 billion yen as an economic stimulus measure to address problems related to bad loans in the central areas of major cities. The Urban Regeneration Policy designated districts as Emergency Urban Development Areas in the central areas of Japan’s major cities. 70% of the land in the Chuo ward was designated as an Emergency Urban Development Area. 1 The Tokyo metropolitan government could thus decide on a Special Urban Development Area in the Emergency Urban Development Area, and a building height was exempted from the height district. Limitations to the floor area ratio in zoning were also deregulated in this area.

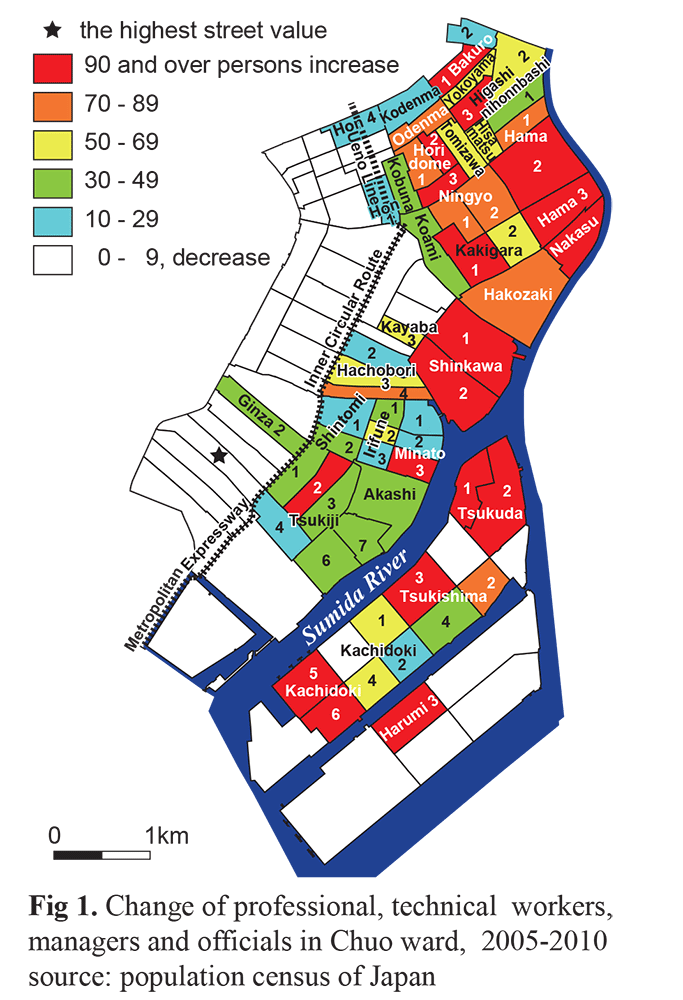

Chuo ward experienced an increase in population due to the implementation of the Housing Linkage Program (fig.1). As the number of single households increased, though, the Chuo ward government revised its housing policy, and the Housing Linkage Program was abolished in 2003 to be replaced by a new deregulation policy concerning the construction of high-rise residential buildings. The ward government also promoted a scheme to increase the number of family households; only long-term residential buildings were allowed to increase the floor area ratio to 1.4 times the standard floor area ratio.

The number of construction disputes increased in the first half of the 2000s; therefore, in 2004, in order to resolve the dissatisfaction with high-rise building construction, the increase in the floor area ratio was reduced from 1.4 to 1.2. Consequently, the number of construction disputes dropped in the second half of the 2000s. During this period, Chuo ward witnessed the highest increase rate (24.8%) of professional, technical workers, managers, and officials in Tokyo. The number of these workers increased in three districts: Tsukishima, Nihonbashi, and Minato.

Tsukishima is located on the south-eastern side of the Sumida River. There were warehouses, and a shipyard in Tsukuda, which is to the north of Tsukishima. Redevelopment of these sites began in the 1980s; high-rise condominiums were constructed, and affluent people started to live there. Nihonbashi is located in the north-eastern part of Chuo ward. Wholesale shops were once agglomerated in this district. However, as the wholesale business began declining, many wholesale shops were replaced by condominiums, which attracted white-collar workers. Developers invested in this district to redevelop the former sites of wholesale shops. Deregulation, such as changes to slant plane restrictions on the sides of building sites, transformed urban landscape.

Minato district is located just two kilometres from the commercial city centre. The district features a manufacturing quarter with print shops and is, as such, an agglomeration of the printing and binding sectors. The district is located close to the Ginza shopping streets and the Nihonbashi business district. The shops and offices in these districts require printed materials, including sales slips and documents. The print shops were small and medium-sized companies. Furthermore, the residences and workplaces of the workers were generally in the same building. After much speculation, investors bought factory sites in the 1980s. The agents of developers were rampant in Minato 2, pouring 35.5 billion yen into the land for four years. 2

The residents of Minato District were displaced, a few of the houses were demolished, and parking lots were established in their place. After the collapse of the economic bubble, a block comprising houses and parking lots was not redeveloped. The terrace-style houses were demolished individually, needing to be propped up on their sides. Vacant parking lots and houses remain in front of the high-rise buildings. The apparatus for elevated parking has been rusting, and a bicycle instead of a car is parked in the parking lot. Two high-rise buildings are shown in fig.2. The high-rise building in the middle consists of rented flats which are one-room apartments. The building on the right is 32-storeys high. As two-thirds of the units in the building have floor space above 40 square metres, more units can be added. The addition of more units to the building was allowed by providing public open space around the building; two blocks were consolidated in order to enable this. Deregulation allowed the erection of dramatically larger buildings than would have previously been allowed, and developers indeed began taking advantage of the changes to build much larger high-rises. The building on the right in fig.2 includes very expensive flats that rent at over 500,000 yen per month, with the most expensive among them priced at one million yen per month. The rent of corporate executives are generally paid by their companies.

In the ways mentioned above, the local government’s urban policy induced gentrification. Former residents could no longer afford to live in these expensive leaseholds, and were consequently displaced.

Professor Yoshihiro FUJITSUKA, Graduate School for Creative Cities, Osaka City University (fujitsuka@gscc.osaka-cu.ac.jp).