( )

https://www.singaporebiennale.org

What’s in the name? What if there’s no person behind the name so it’s just the name? If the name evokes more than one person, who is going to answer when it’s called? Why do we name the unnameable or the unnamed? Who still remain nameless and stay with us?

1.

Natasha manifests when we undo the wor(l)ds as we know. By undoing them, we arrive at the “matrix” of life: home, family, and other relationships, whether of friendship, love, hate, or simply womb. Simultaneously, by undoing, we also land at home as earth – that is, the family of and in relationship with other species, non-animate beings like stones, or invisible presences like ghosts or spirits. A biennale is an exhibition of contemporary art – along with other programs – taking place biannually and mostly organized in large scale, grabbing many resources including attention. It’s a festivity, a ceremony, a statement, a momentum, or all of them. The Singapore Biennale 2022 is named Natasha. Given a name, Natasha pushes against our normative knowledge and ways of knowing - even including the biennale itself - to become minor, small, nothing, and to be something again. It’s the invitation for an encounter, as in a journey to face the meaning of life again.

Group portrait: Singapore Biennale 2022 Co-Artistic Directors. From left: June Yap, Nida Ghouse, Ala Younis, and Binna Choi. Image courtesy of Singapore Art Museum.

Likewise, the life of the artist matters in relating to their works. It’s life before art or art in life. The encounter may enable us to practice different ways to relate to one another, ultimately towards what I would like to call “impersonal fellowship.” This idea is borrowed from theoretical physicist and theorist of mind David Bohm. He said, “The point is that we would establish, on another level, a kind of bond, which is called impersonal fellowship. You don’t have to know each other. In England, for example, the football crowds prefer not to have seats in their football stands, but just to stand bunched against each other. In those crowds very few people know each other, but they still feel something – that contact – which is missing in their ordinary personal relations. And in war many people feel that there’s a kind of comradeship which they miss in peacetime. It’s the same sort of thing – that close connection, that fellowship, that mutual participation. I think people find this lacking in our society, which glorifies the separate individual. The communists were trying to establish something else, but they completely failed in a very miserable way. Now a lot of them have adopted the same values as we have. But people are not entirely happy with that. They feel isolated. Even those who “succeed” feel isolated, feel there’s another side they are missing.” 1

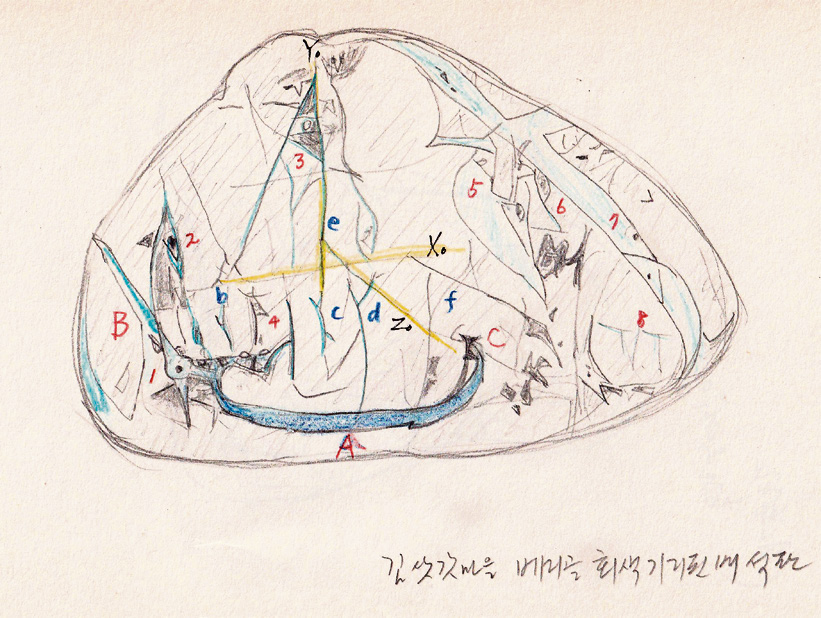

Fig. 1-2: The photograph (draft, unedited) taken by Kyongtae Kim shows a stone tablet as part of the collection by Shin Beomsun, where the Queen Shyashya and her princess make their appearance. Kwon Koon painted ten different tablets from the collection. One of them is what’s presented in Figure 1 (Photograph by Youngtae Kim).

Figure 2

2.

Note to take: it may well be that, without names, a family, a community or any other relationship can maintain their relationship of love. There’s something immense behind the names, not in the names. The names are the incomplete agent and rather might perform an act of distancing, a way of objectification as in the colonial custom. So the name at best might be an index, an agent of the relationship in question. Anonymity can be an act of love.

3.

“While the COVID-19 pandemic has changed the way we used to live by suspending ordinary life, and causing the loss of many, we now witness a process of normalization, whether voluntary or forced. Many biennales have also celebrated this ‘return’ of post-pandemic, with a renewed hope for a world different from what we live(d) in. Visiting Natasha is not only to return, but to be conscious of the values most intensively experienced during the pandemic: intimacy, living the unknown, the capacity to adapt, realizing other possibilities of living and relating to the world.” –A collective voice from us, co-artistic directors of Singapore Biennale 2022

Fig. 3-4: The photograph (draft, unedited) taken by Kyongtae Kim shows a stone tablet as part of the collection by Shin Beomsun, where shapes evoke the forms of ships, gyryffyns, and syamyan. The sketch by Shin is presented in Figure 3.

Figure 4

4.

Shin Beomsun [신범순] is one of the “artists” contributing to the Singapore Biennale 2022. Shin is Professor Emeritus of Korean Literature at Seoul National University. He never made or exhibited an artwork, but he has an expanding collection of small stones that he found over last few years. Every day he sketches them, one after another, in order to read them carefully and closely. They show beings – numerous beings – whether they are shamans, cheonsa (angels in Korean), princess and queen, or mythical bird-cum-lion like a griffin. Shin, however, named them somewhat differently: “shyamyan" rather than shaman, “tenshya” rather than cheonsa, “gyryffyns” rather than griffin. A queen is named, or has the name, Shyashya. Queen Shyashya is composed of multiple and endlessly weaving lines of gyryffyns. There’s no foreground or background. One form of being lends to another to make a multitude of forms or beings. One could say, a joyful and vital form of co-existence is Queen Shyashya. The story of Queen Shyashya is a redemption of the lost language or lost “paradise” as told by the Little Prince. Shin believes there’s a fairy tale prior to myth. The tales are the stories that honor the creators or creating principle of the world. Petroglyphs are a pre-text of such tales. Small ancient stone tablets make the stories travel, available for discovery by those who seek for them.

Natasha draws artists from the edge of – or even outside of – the field of contemporary visual art. It’s not to insert the “outsiders” into the “inside.” Rather, it’s asking all to be outsiders from what and where they used to do. Natasha is a means of undoing knowledge or ways of knowing as we know, to say it again. Thus ask: What do we know about art? What does art do? Where to find art and artists? Shin guides us back to the basics yet the fundamental: a way of seeing, the question of who I am and how this “world” is created. We journey into other kinds of temporality and in different directions – e. g., we track back far and far to a long past in order to reach a near future.

5.

Salutes, and stories. This short text is composed during my research trip to Phnom Penh together with Ala Younis, one of the other co-artistic directors. Our time here is short and yet dense, as guided with care by performing artist and organizer Sinta Wibowo, artist and designer Tan Vatey, actress and observer Ma Rynet, artist Tith Kanitha, and filmmaker Davy Chou (Anti-Archives). Along the way, we meet many, This includes Kavich Neang of Anti-Archives, a filmmaker who once was a traditional Kmer dancer; Meta Moeng, who recently relocated the Dambaul Reading Room to share the building at the Anti-Archives; Arnont Nongyao, sound artist from Chiang Mai, in the middle of his workshop with local artists, curators, and neighbours at Rong Cheang: A Community Art Studio. Sorn Soran welcomed and introduced us to his practice of Cambodian shadow puppetry. Bertrand Porte, archaeologist and curator at Musée National du Cambodge, also showed and shared stories around un-exhibited sculptures and objects in his workshop, where the rich and complex history and culture of Cambodia are integral. In the place where no institution of contemporary art is established, there are branches of friendship, fellowship, broken hearts, and healing that grow out, give shadows, and move the breezes. This research trip would lead us to enable many of colleagues and friends to take a journey and “salute” in the rich yet tearful land of Southeast Asia towards the end of the Biennale, where everyone met or found something of Natasha and came and put together those pieces of a puzzle, if not a forest. At this moment, for my own path to Natasha, I hold on to a piece of stone tablet where from gyryffyns to the Queen many beings buzz towards an opening.

https://www.singaporebiennale.org

Binna Choi is a curator and the director of Casco Art Institute: Working for the Commons in Utrecht, the Netherlands. She is affiliated with different bodies and spirits around the world. Email: binna@casco.art