The Colonizers’ Spoils: The Zanryu-Hojin Exiled between Politics and Society

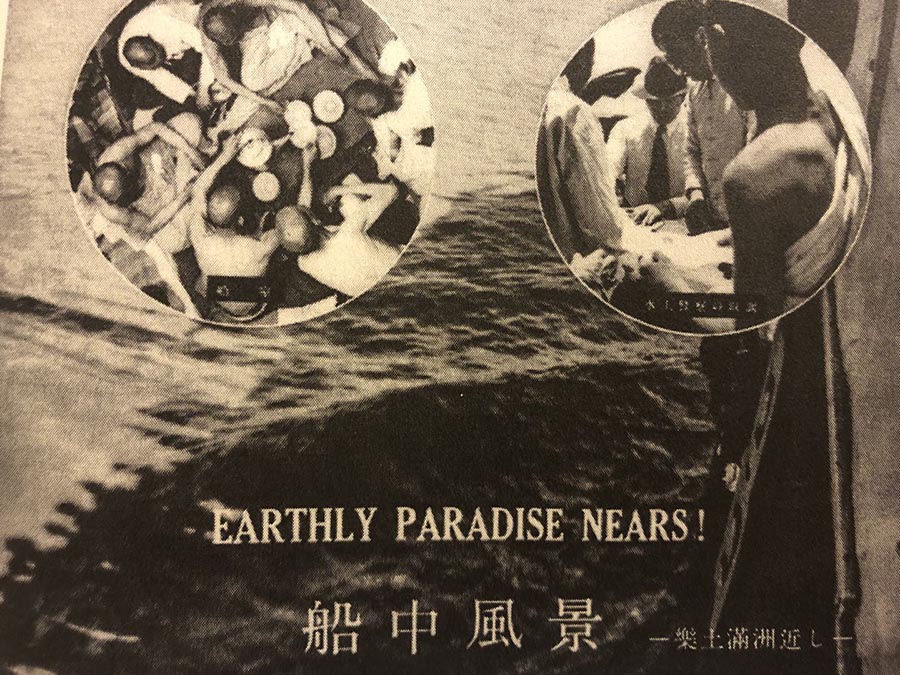

After the Japanese invasion of Manchuria, the puppet state of Manchukuo was established. Japanese imperialists promised a ‘Paradise on Earth’ to counter Communism and the West. To build this ‘Paradise,’ the Yamato race was to lead other Asian ethnicities. Facing a shortage of colonists, Manchukuo's propaganda targeted the surplus rural, impoverished population in Japan. ‘To Manchuria!!’ (滿洲へ!!), echoed the call: the ‘promised land’ was near (樂土滿洲近し). One million peasants, persuaded or coerced, were dispatched to remote kaitakudans (開拓團, agricultural settlements) along the Siberian border.

Amid the Pacific War, Japan recruited soldiers from Manchukuo, leaving a skeletal garrison in the region. The worsening situation favored the Soviets, who invaded Manchuria in August 1945. Instead of warning Japanese settlers, the Kwantung Army (关东军) sponsored mass suicide. Those who did not commit harakiri or die during the confrontations became ‘refugee-hostages,’ facing inhumane conditions under Soviet control. Japanese women in ‘refugee-hostage’ camps were coerced into sexual relations with Soviet soldiers for supplies. The camps became markets for cheap labor and advantageous marriage agreements for Chinese farmers. Many women saw in it a way out, avoiding collective rapes, diseases, hunger, and death. Kidnappings of Japanese children were also common. Nine months after Manchukuo's fall, in May 1946, the Japanese government began repatriation policies, generically categorizing those left behind as zanryu-hojin (殘留邦人, literally “remaining Japanese”). Girls over 13 were labeled as “remaining women” (zanryu-fujin, 残留婦人) implying that they had chosen to stay and should, therefore, not enter the repatriation process. Other women who managed to disembark in Japan were subjected to ‘racial cleansing’ operations. The state enforced biopolitics, forcing abortions to prevent racial contamination and barring entry into the country of women married to a male foreigner.

As Sino-Japanese relations worsened in May 1958, the 30,000 ‘missing’ Japanese in China were politically killed by Tokyo in official registries – another step toward gradual oblivion. During the Maoist era, the zanryu-hojin concealed or self-suppressed their Japanese identity. Despite normalized relations in 1972 between the PRC and Japan, as far as Tokyo was concerned, the zanryu-hojin issue could remain in the shadows of history. It did not work out that way, largely due to the civil initiative prompted by Yamamoto Jisho (山本慈) in Japan and the requests of orphans in the Japanese embassy in China to find a solution for their predicament. From 1981 to 1985, timid efforts were made to reunite the zanryu-hojin with their Japanese families. By 1986, only 37.8 percent had found relatives, and from 1986 to 2007, just 31 percent of the reclaimants got positive family identifications. We can understand Tokyo's reluctance in terms of a strategy to let the issue run out of steam by constantly stalling until everybody caught up in the failed actions in Manchuria was dead.

Fig. 2: Japanese poster portraying Manchukuo as an ‘Earthly Paradise.’ (Reprinted in Annika A. Culver, Glorify the Empire: Japanese Avant-Garde Propaganda in Manchukuo. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, p. 113: Manchuria graph. August 1938, Yumani Shobô 2008 reprint, Duke University Perkins-Bostock Library Collection)

Those who completed repatriation were confronted with the hardships of illiteracy and language difficulties, which undermined their full integration into Japanese families. They found precarious, poorly paid, and harsh conditions in their struggle for economic survival. For a long time, and as part of the repatriation policy designed by Tokyo, the zanryu-hojin needed a guarantor (not always available or willing), which reinforced the ‘dependent’ status of the newly-arrived ‘Chinese-Japanese.’ After all, they had to leave behind one or more members of their Manchurian families to return to Japan. Subalternity and exilic existence were the state of normality conferred on these once-useful individuals by the post-imperialistic State, a State that constantly tried to erase them even from the fringes of history, alongside the shame of a defeated Empire.

André Saraiva Santos, University of Aveiro, Portugal. Email: andressantos@ua.pt

The full Portuguese-language version of this article originally appeared in Afro-Ásia under the title “Despojos do colonizador: os zanryu-hojin exilados entre a política e a sociedade” (n. 61, 2020, pp. 191-227). Available at https://periodicos.ufba.br/index.php/afroasia/article/view/31885