Chinese Folk on Flimsy Grounds

In contemporary China, the museum is commonly viewed as a repository of knowledge and a site for educating the public. As an official institution, the information on display is rarely questioned or authenticated, but is rather accepted as indisputable fact. By critically analysing the exhibits in the Chinese Folk Art Museum in the Majie village of Baofeng county, Henan province, I hope to demonstrate how the historicity and folkness of Chinese performing arts are constructed through largely fragmentary – and sometimes mistaken – narratives, thus painting an image of an apolitical China.

The Chinese Folk Art Museum (zhonghua quyi zhanlanguan中华曲艺展览馆) claims to be the first museum to comprehensively showcase all forms of quyi 曲艺 (storytelling art) 1 and introduce the Majie Folk Art Fair (majieshuhui马街书会, hereafter the Fair) to the wider public. As the largest existing folk art fair in contemporary rural China, the Fair is advertised as a sacred place for performing artists to congregate and share their skills and repertoires on the 13th day of the first lunar month every year. In the annual gathering, the performing artists are also expected to be invited by the audience to perform for their wedding ceremonies, postnatal birth ceremonies, or even funeral rites, thereby earning some income. The Chinese Folk Art Museum was part of a larger government project of conserving, if not entirely reproducing, the Fair after it was granted the status of intangible cultural heritage (ICH) by the state in 2006. According to the museum exhibit, this festive event has been in existence for over 700 years.

Under the authority of the Baofeng government, the museum was to imitate the architectural style of the Yuan Dynasty, because the Fair is believed to originate from the second year of the Yanyou period of the Yuan Dynasty (1315) [Fig. 1]. It consists of two floors. The first floor exhibits the history of Chinese folk art as curated by the Chinese Quyi Artists Association, while the second floor showcases the development of the Fair and is managed by the Baofeng Federation of Literary and Art Circles. Although this ten-year-old museum presents no archaeological discoveries, it attempts to create a sense of antiquity by appropriating ancient Chinese architecture and interior decorations. It also serves to achieve the official agenda of “fulfilling the developmental strategy of rejuvenating the nation through culture,” as indicated in its introductory statement. However, the museum tends to highlight the historical density of quyi and subtly attributes the operation of the Fair to the motivations of the commoners in order to portray a depoliticised China, as I will show in the following discussion.

An ancient folk

Walking into the museum, visitors begin their tour on the first floor in a prescribed order through three sequential sections: (1) Overview of Chinese Folk Art, (2) Brief History of Chinese Folk Art, and finally, (3) Significance of Folk Art in Chinese Art History. All information is narrated through texts and pictures. Despite having no archaeological artifacts as historical evidence, the exhibit strives to highlight two central points: the long history of quyi and its roots in minjian 民间 (“folk”). But both of them are inconclusive, as the first point is supplied with speculative statements, while the second one is supported with histories indicating exactly the opposite – namely, that quyi was more elite than folk.

The ‘long history’ narrative starts from the first section (Overview of Chinese Folk Art), where one learns that quyi can be dated back to “ancient times” and “later thrived in small tea houses and wine shops and gradually became a culture inherited by people of all generations.” It continues in the second section (Brief History of Chinese Folk Art), beginning with a statement that “the origin of quyi can be traced back to the old age, but little of its history can be corroborated.” Following this is a specific remark that no document can substantiate the existence of quyi before the Han Dynasty. However, at this very point, the museum does present sources – such as gumeng shuochang瞽矇说唱 (musician’s oral storytelling performance) and paiyou biaoyan 俳优表演 (actor’s entertainment performance) of the pre-Qin period, which served to advise and entertain emperors – to indicate that there are common artistic attributes between quyi and the pre-Qin performances. Such unapologetic description relies on visitors’ ability to imagine the historical depth of quyi without any direct evidence. More importantly, neither their historical functions nor the context of the imperial court could firmly verify that quyi is rooted in minjian. In connecting quyi to earlier forms of oral storytelling and entertainment performances, the museum is able to articulate quyi’s antiquity on somewhat flimsy grounds.

As one moves onto the quyi of the Han and the Northern and Southern Dynasties (206 BC-589), baixi 百戏 (hundred shows) is introduced as testimony to the emergence of folk performing arts. This mentioning is supposed to illustrate how quyi is rooted in minjian. But as no further details are offered here to explain what baixi was, it is difficult to discern what exactly constitutes its folkness. According to Zhao, baixi refers to “variety entertainment consisting of music, song and dance, acrobatics, comic skits, circus games, martial arts, magic tricks and so forth,” 2 popular between the Han (206 BC-AD 220) and the Six Dynasties (220-589). They were performed for commoners in public squares, apart from for nobles in courtyards, a royal palace, or a palatial mansion. 3 To this extent, one may find some affinities between the folkness of quyi and the audience and the venue of baixi performances.

It is later explained that quyi had matured since the Tang Dynasty (618-907), and subsequently, due to the ever-growing urbanisation during the Song Dynasty (960-1279), street theatres facilitated the development of these entertainment activities. Here, performing in street theatres is specifically regarded as a reflection of “the state of minjian.” The narratives of the quyi history from the Jin and Yuan to Qing Dynasty in the museum further stress an increased appreciation and consumption of popular culture in the society and the changes in quyi. It is implied that new performing art forms such as zaju 杂剧 (variety theatre), shuoshu 说书 (storytelling), and sanqu 散曲 (song poetry) became popular at both court and among the populace in the Jin Dynasty (1115-1234) and the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368). The Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) witnessed another peak point of quyi as print technology greatly facilitated the dissemination of quyi, dramas, and vernacular literature, satisfying the popular demand for entertainment. During the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912), given that many performing arts absorbed local dialects, music, and customs, distinctive regional genres proliferated, from rural countryside to urban areas. A multitude of repertoires have survived until the present.

Admittedly, delineating an exhaustive history across centuries is a challenging task. However, to categorise quyi as folk art is problematic. First, they were not defined as the art of the folk; rather, from the Han to the Qing Dynasty, they were performed for the folk – in this context, the commoners and later the urban dwellers – and in public places outside of the imperial court and in urban areas. But quyi was never exclusive to the folk. Performances also took place in the imperial court. In this sense, quyi could have been called ‘court art’ as well. Second, if the popular base is one of the core criteria to qualify quyi as folk art, the dating of quyi to the pre-Han period becomes rather misleading. It appears to insinuate a lengthier version of the quyi history. The contents of the exhibit do not explain the direct conceptual relationship between quyi and folk art. The two are conflated on an epistemological level through an arbitrary usage of minjian to reframe quyi. Even the name of the museum is translated into English as ‘Chinese Folk Art Museum’ instead of a more literal ‘Chinese Storytelling Art Museum.’

The whole history of Chinese quyi is also conveniently truncated. Performing arts were deployed as a medium of propaganda for anti-imperialist and anti-feudalist wars during the era of Republican China, and they served to legitimise the political power of the Chinese Communist Party after the founding of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). All of this, however, is completely unacknowledged in the museum. According to one of the curatorial team members, the reason why the exhibit excludes the history of quyi after the PRC was established in 1949 is that there is a lack of visual and textual materials due to wars. But this justification can be easily rejected, because there exists a plethora of published materials and sources on the quyi history during the PRC era. 4

Regardless of the intention behind the curation, the partial rendition of history has political implications. From the perspective of an audience, the exhibition chronicles a narrative rooted purely in the sentiments of the folk, as if devoid of any political contestation. The unconsidered obviation of quyi after 1949 encompasses three major historical periods. Under the Maoist regime, performances that contained ‘superstitious’ and ‘vulgar’ contents were reformed to convey socialist policies and values, thereby consolidating the Communist ideology. In the reform era, those performed in rural areas were also used as soft power to build a presumably socialist spiritual civilisation and a harmonious society. 5 In the new millennium, many of them were inscribed in the National Representative List of Intangible Cultural Heritage. 6 The omission of such context in the museum could be a strategy to ensure that the exhibit is not politically charged. The seemingly apolitical past of quyi in ancient China thus fabricates a romantic notion of folkness, one that connects all Chinese people to this shared culture.

A contemporary folk

The troubling curation does not end on the first floor. The long history of the Fair exhibited on the second floor can be called into question as well. For instance, according to the timeline that chronicles the history of the Fair in the second section (Majie Folk Art Fair), the evidence that justifies the materiality of the Fair is circumstantial, as it simply points to the construction of the Guangyan Buddhist Temple in the Majie village in the Yuan Dynasty (in 1315) and its subsequent restoration in the Ming Dynasty (in 1496). We can also observe that the other narrative in the first section (Origin of Majie Folk Art Fair), which draws the connection between the Fair and the Jingkang Incident (1126-1127) during the Northern Song Dynasty, is utilised to re-periodise the history of the Fair. It is recounted that during that period, “Majie area served as the assembling point for performing artists who were seen as an important force resisting the invasion of the Jin armies,” and hence, by inference, the existence of the Fair. As such, the chronology of the Fair can be further stretched to the Song Dynasty “between the first year of the Jingkang period of the Northern Song dynasty and the seventh year of the Shaoxing period of the Southern Song dynasty” (1126-1137). Certainly, the latter narrative can lengthen the history of the Fair. But neither Buddhist temple nor the Jingkang Incident can be proved to be relevant to the Fair. Unrelated events seem to have been inserted to corroborate the chronology to reinforce the facticity of the emergence of the Fair.

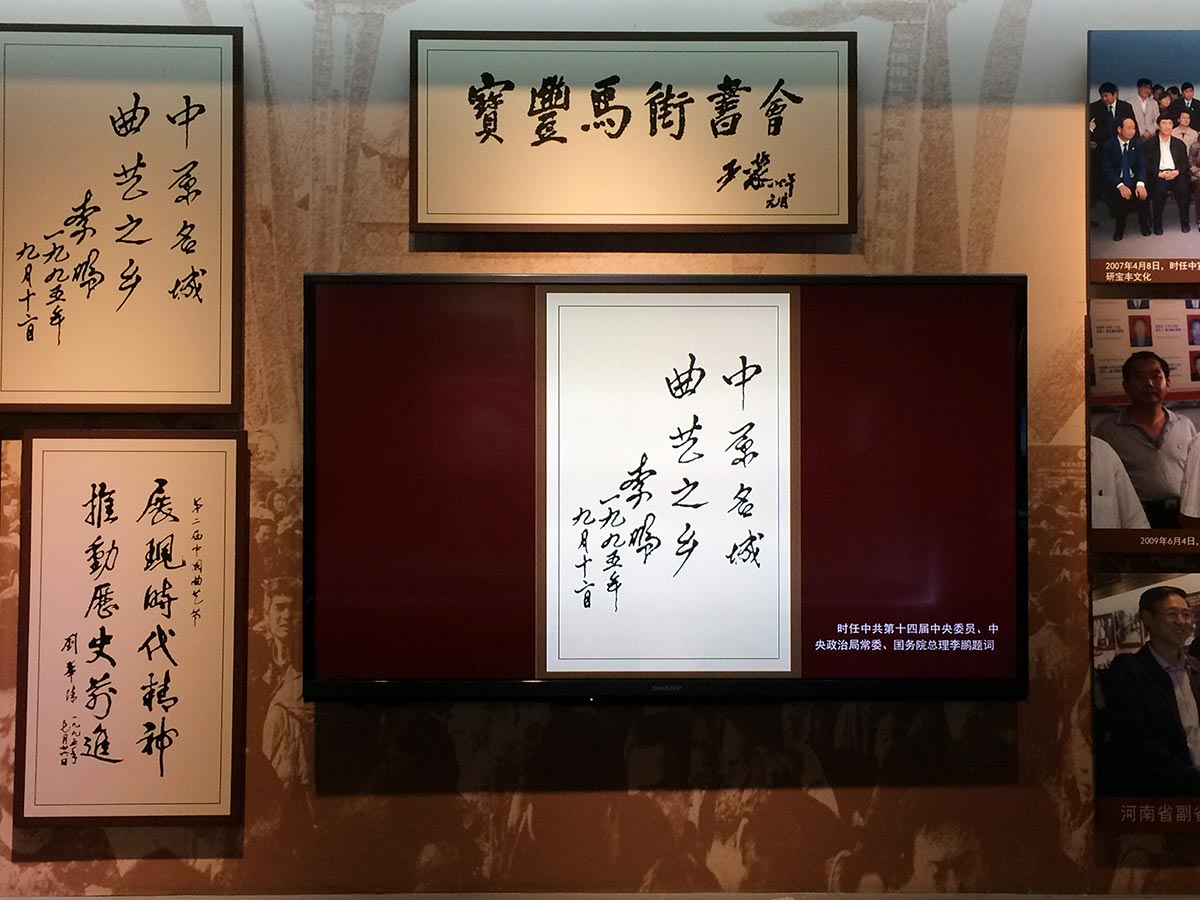

Following that, the historical events indicating that the Fair thrived in the Qing Dynasty (1863), Republican China (1928), and PRC (1963-1965) are also fragmentary. It was not until 1980 that the documentation of the Fair became relatively consistent. Major events and achievements are recorded annually in the timeline that terminates in 2014, when the museum was officially opened. Exhaustively listed in a chronological order, they focus on officials’ inspections and supervisions, scholars’ research visits, and renowned professional storytelling artists’ performances. Such an emphasis on the authorities’ efforts in developing the Fair in the past four decades is reinforced in the last two sections. Inheritance and Development (chuancheng yu hongyang 传承与弘扬) highlights new activities such as the ‘Performance Auction’ invented by the Baofeng government particularly for the purpose of safeguarding the Fair by providing a market. 7 This is because, owing to the decreasing demand of performing arts around the early 2000s, many performers have stopped performing. By arranging the local government-owned work units and local enterprises to bid the performances, the auction was intended to show the possibility for the performers to sell their performances, thus encouraging them to continue performing at the Fair to keep it alive. Moreover, inviting celebrated artists to perform at the Fair serves to stimulate a celebrity effect to attract more visitors. 8 The last section, Leader’s Care (lingdao guanhuan 领导关怀), reserves an exclusive place to present the encouragement and support of the Fair by officials at different levels. Visitors are expected to encounter a wall of memorabilia consisting of framed calligraphic works written by eminent government officials, some of which are written for the Fair, whereas others represent officials’ endorsements of performing arts and the Fair [Fig. 2].

Fig. 2: Leaders’ Care section in the Chinese Folk Art Museum (Photo by author, 2017).

Compared with the exhibit on the first floor, the Fair is curated with a strong governmental overtone. It is not common to expose the ‘invisible hand’ of the government operating behind heritage conservation efforts in a museum setting. Even the presence of celebrated professional artists represents a certain officialness, as these artists occupy positions in state-funded organisations such as the Chinese Quyi Artists Association. This is probably because the available materials gathered by the local curatorial team largely come from the Compilation Committee of Local Records of Baofeng county, whose methodology directs the archivists to document the history of the authorities. 9 The local curatorial team explained to me that the Fair’s sustainability relies heavily on the leaders’ educational background, especially that of the head of Baofeng county and the Party Secretary. It seems that the leaders are entirely responsible for determining whether the Fair deserves any attention. 10 The Fair would have more events and activities if the leaders themselves were keen on reinvigorating performing arts.

But this has an unavoidable consequence: the showcase of a folk art fair becomes that of authorities. If we look at the part in the exhibition that has less traces of government involvement, we can conclude that the folkness of the Fair is constituted by the status of the performing artists who are not officially affiliated nor practicing quyi as a profession. They make up the majority of the artists at the Fair, and they are the subjects of the photographs in the second section. In these photos, they participated in activities like xieshu 写书 (selling performances) and liangshu 亮书 (showcasing performances) [Fig. 3]. The photos demonstrate little sense of time. Their captions do not suggest when the photos were taken and by whom. They are snapshots of arbitrary moments collated in a montage to give an impression of historical depth and to imply the unchanging state of the Fair. While the snapshots showcase the folk performing artists’ participation in the Fair, the Fair’s history as represented through textual descriptions of the timeline prioritises officials, researchers, and professional performing artists’ contribution to the Fair’s development, all of which undermine the primary role of folk performing artists in sustaining the Fair. By underlining government officials’ supervision in the museum exhibit, the officials become the pillar of the Fair, ensuring its Folk performing artists, on the other hand, appear to be the group of people with more participatory power in making the Fair a folk phenomenon, yet with less decisive power in determining its course of history.

Fig. 3: Photos of Folk Performing Artists in the Chinese Folk Art Museum (Photo by author, 2017).

In 2016, as I was conducting my fieldwork, I encountered a local resident who complained to me how recklessly dictatorial the local government was in requisitioning her farmland to ready the field for the 2016 Majie Folk Art Fair. As the Fair is believed to have been traditionally organised on the grain field, the local government ordered the local farmers to empty the land with only ‘traditional crops’ such as grain allowed to be planted. Many farmers refused to cooperate. They planted pear trees to protect their land from being requisitioned since only by doing so could they prevent their land from being trampled by the crowd during the Fair. Unfortunately, during my visit, the pear trees were uprooted. However, to my surprise, the farmer mentioned above changed her attitude the moment I told her I would visit the Chinese Folk Art Museum. She expressed her fondness for the museum and told me that she had visited it numerous times and had learnt the history of the Fair. 11 Her discontent with the local government co-existed perfectly with her sense of pride about the Fair, derived directly from her experience in the museum. She is not an exceptional case. Many local visitors were impressed by the exhibits. Before visiting the museum, they knew very little about the Fair’s extensive history. But a sense of pride is immediately evoked after visiting the exhibition as they learn that such ancient tradition originates from their hometown and has since received official acknowledgement. In a way, the museum becomes a space that inculcates a sense of ‘imagined community’ as the visitors learn to become part of the collective folk, sharing identical pasts and futures. The authorities’ callous handling of the Fair behind the scene and the displeasure of the local farmers in the requisition of land are all but concealed.

Connecting the locality to a longer history of ancient and Republican China re-structures the Fair’s fragmented past; in return, the Fair serves as an evidence to prove that quyi is in actuality locally grounded. The museum juxtaposes the ancient and linear past of quyi with the fragmented present of a contemporary folk art fair to compose a cultural imaginary devoid of any political tension. By all means, this is a reflection of the current ideological emphasis on ‘the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation,’ which leaves no room for any reminiscence of the politicisation of culture prevalent during wartime and socialist China.

Wang Jiabao is a Lecturer at the Faculty of Creative Arts, Universiti Malaya. Her research focuses on the genealogy of the discourse of ‘folk’ or minjian in modern and contemporary China. Email: wangjiabao@um.edu.my