Chinese export paintings in Dutch public collections: a shared cultural visual repertoire

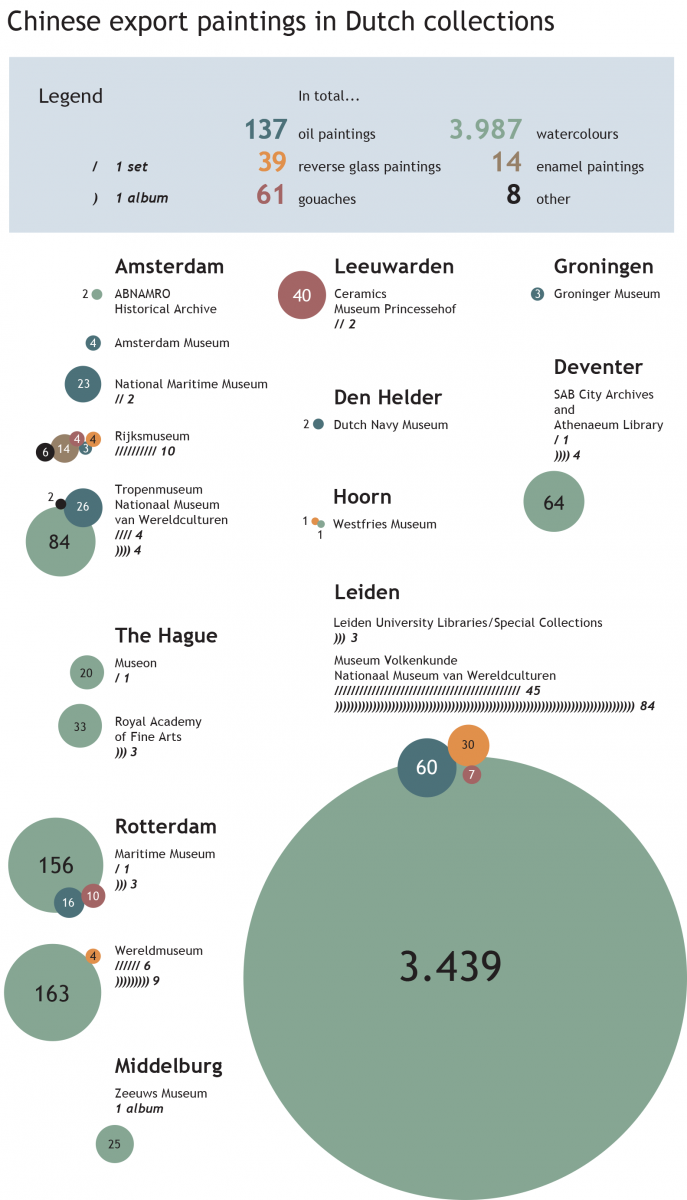

The collections of seventeen museums, archives and libraries in the Netherlands include a large number of Chinese export paintings (see infographic 1), many of which have finally been unveiled thanks to the new publication Made for Trade – Made in China. Chinese export paintings in Dutch collections: art and commodity.1 Existing research on the corpus deals mostly with the transfer of stylistic aspects; Western and Chinese painting conventions; literary sources; historical models; socio-cultural and aesthetic differences; dating and iconographical issues; and technical analyses regarding conservation of pigments and paper. In contrast, Made for Trade puts a new focus on these paintings: to see them as meaningful information carriers of an unknown culture that derive their legitimacy from the historical China trade,2 and to draw upon current theoretical approaches for treatment of these transnational works of art in future museum practices and strategies. Made for Trade follows the entire trajectory of this specific transcultural painting genre, from the production two centuries ago to the current position. At work in this trajectory are mechanisms between people, institutions and the paintings, which increase or, indeed, diminish the appreciation of this time- and place-specific art.

Terminology

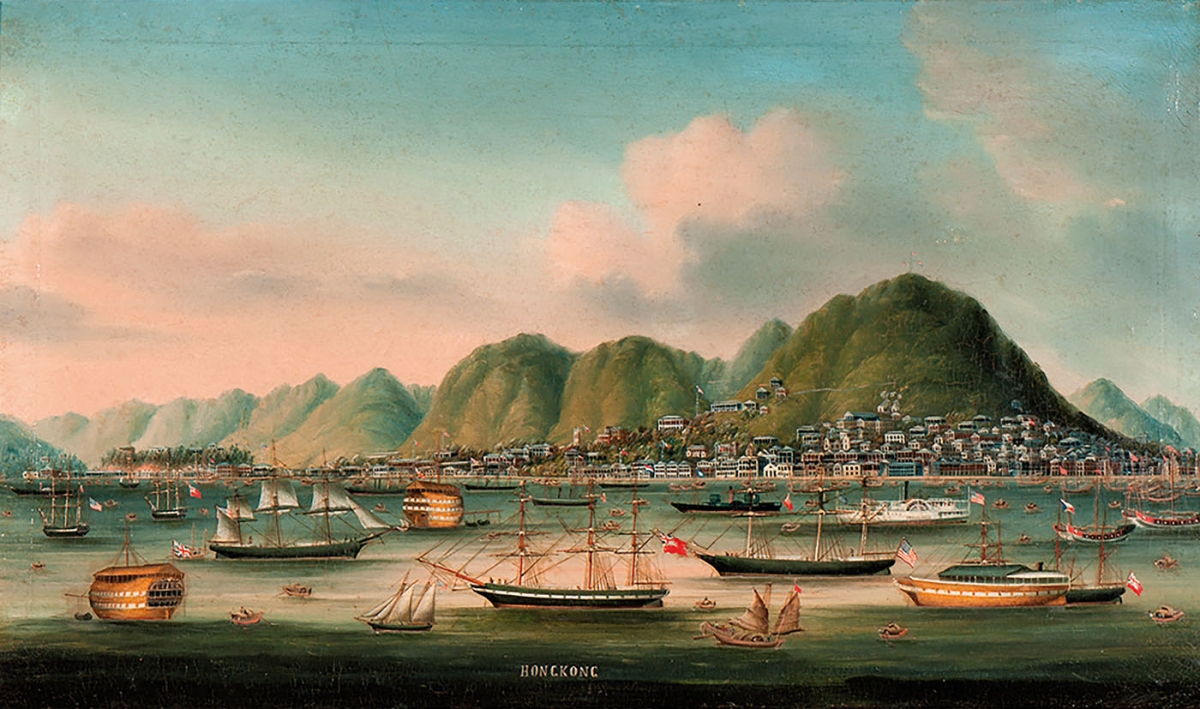

The term ‘Chinese export painting’ was coined by Western art historians,3 following the precedent set by the term ‘Chinese export porcelain’, in order to distinguish this type of painting (yáng wài huà or wài xiāo huà) from traditional Chinese (national) painting (wén rén huà or guó huà), making clear that these works were made for export to the West.4 These artworks are also called ‘China trade painting’ or ‘historical painting’, positioning them in the historical China trade, the most important forms of which were porcelain, tea and silk. The terms are used interchangeably in Europe, Asia and North America. From the place and time of their production in Canton and Macao, later spreading to Hong Kong and Shanghai, until long after, these paintings were described by their contemporary makers as ‘foreign paintings’, ‘foreign pictures’, ‘paintings for foreigners’ or ‘Western-style paintings’; whilst foreign, Western buyers in that period just called them ‘Chinese paintings’.

In 2015, Anna Grasskamp introduced a new term for artworks derived from trade and cultural interactions between Chinese and Western nations within the framework of visual culture. With the use of the word ‘EurAsian’ it is possible, she argues, to escape “binary divisions into ‘European’ and ‘Asian’ elements, clear-cut ‘Netherlandish’ or ‘Chinese’ components.”5 This term is indeed highly appropriate for objects and images that are labelled ‘Western’ and which, in turn, are modified, re-framed and re-layered by Chinese artists and artisans into new, innovative and complex ‘EurAsian’ objects. However, this term is only partially suitable for use when discussing Chinese export painting overall. Although, in general, the use of the label ‘Chinese’ is in many aspects problematic, the commonly accepted and most universal reference, ‘Chinese export painting’, seems the most appropriate one to use and comes closest to the description of the phenomenon.

Valuable export goods

Chinese export paintings have for most of their existence been seen as lacking in intrinsic artistic value, which may explain why they have not received their deserved attention, and why they generally lie forgotten and undusted in museum storerooms. The label ‘export ware’, however, should not discount these paintings as art. In addition, with the passage of time, they are currently appraised as valuable collectibles, heirlooms and antique ware, and their subject matter makes them exemplary educational objects. They have a historic, artistic and material value. Rich stories emerge from them. Stories about the most important actors in this Eurasian arena: the painters, their studios, the market, the techniques and methods, materials and various media, and the depicted scenes. These multi-faceted aspects make the paintings significant for contemporary viewers. The scenes depicted potentially teach us about social world history, globalisation and glocalisation, transport, architecture, international trade, former daily life in the Pearl River Delta and mutual exchanges between Europe, North America, China and other Asian countries in the late eighteenth to mid-nineteenth centuries. Moreover, cross-cultural ideas about beauty, connections between trade and collecting, and this particular integrated, blended, transcultural painting phenomenon as a whole, are additional properties that constitute the potency of these paintings. We must take these capabilities into account when we evaluate them as a special artistic phenomenon, and a shared cultural visual repertoire with its own Eurasian character.

This confluence of values makes Chinese export painting distinctive as an art phenomenon that needs to be treated as a class in its own right. Far from being just commercial paintings produced by profit-making Chinese artists in the Pearl River Delta, as transcultural objects they at that time conveyed the richness of a culture and, as such, operated as valuable vehicles in the construction of reality in the historic China trade period during the Canton System (1757-1842), and long after. These paintings possess equivalent signs of the inherently collective and blended culture of the place of their production. Moreover, it is this interpreted Chineseness that makes this art genre interesting and valuable to modern eyes and hybrid audiences around the world.

Research provides not only more knowledge about the constructed and subjective image of China that these paintings brought with them to the audiences in the West, but also highlights the value of the Dutch joint collection, which deserves to be accessible and must be safeguarded for future generations.

Chinese export paintings were so appealing to foreign trading powers active in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries that they can now be found in museums and private collections around the world, mostly in Europe and America, with only a few in China, mainly in Macao and Hong Kong. Currently, a growing number can be found in (newly established) museums in other cities in China,6 including in Guangzhou where the study of the historical China trade episode has seen a remarkable revivification of late.7 A focus on the Dutch collections is justified due to, among other reasons, the dearth of interest in the Netherlands for this topic and the worldwide lack of awareness of these collections in contrast to the leading collections of Chinese export paintings around the globe. Made for Trade helps to convert these paintings from forsaken items in museum basements to centralised artworks, through a new act of inventory.

Representing China to Dutch audiences: a new corpus unveiled

Chinese export paintings functioned as part of a ‘meaningful whole’ in Dutch society at the time of its historical China trade during the nineteenth century. Unfortunately the paintings failed to maintain their high status and value throughout the twentieth century, only to see a revival a hundred years later (see inset below). As a result of the fluctuating zeitgeist, the Dutch collections now include paintings ranging from forgotten and neglected items in the storerooms of (mainly) ethnographic museums, to the unique and excellently restored paintings in the Maritime Museum Rotterdam, the Groninger Museum and the Amsterdam Rijksmuseum. (fig. 1) The Chinese export paintings collections in the Netherlands consist of over 800 inventory numbers, with more than 4000 paintings, of which about 3000 belong to the valuable and extensive Royer Collection held at Museum Volkenkunde/National Museum of World Cultures. (fig. 2)

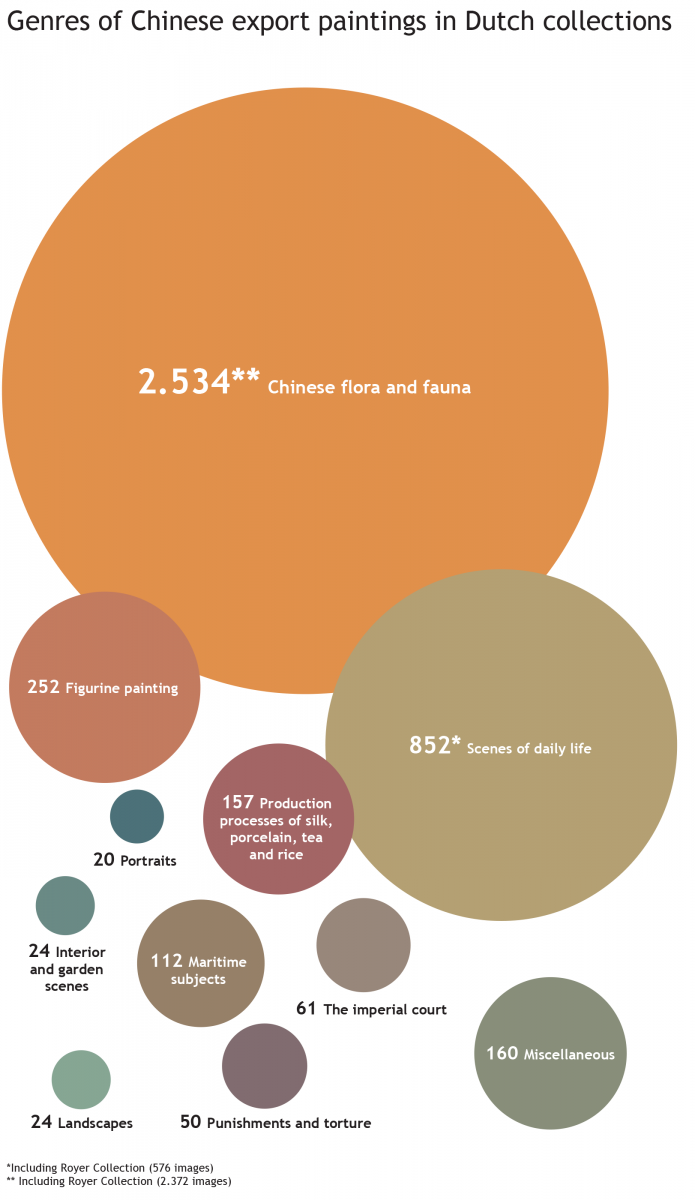

Among the various types of works, sets or albums can be distinguished, whose documentary and serial natures, often constructed around one theme, contribute to the individual images, adding to their value. Together, the images form a narrative that, in a logical and coherent manner, makes the unknown ‘exotic’ scenes familiar and thus tells a meaningful story. As a kind of ethnographic souvenir, albums with titles such as ‘costumes of China’ or ‘daily life in China’ are, as Yeewan Koon calls them: “compelling ways of translating China.”8 Furthermore, the corpus can be regarded as a large dataset of painted media with a variety of genres with Chinese subject matters. (see infographic 2)

Image of China

These images were never just innocent renderings of the world, and so we must evaluate Chinese export paintings with great caution, especially when they are presented as veritable historical sources. All these artworks were produced as a result of cultural and trade relations at work between the Netherlands and their trade zones all over Asia, specifically in China and the East Indies. The scenes were generally constructed, copied and reconstructed, sometimes even creatively devised by the Chinese painter, with most of them tailor-made for Western customers; as a result the various genres shaped a (distorted) image of those foreign countries, then and today.

The high demand for export paintings led to the need to standardise and copy scenes. In the well-known Chinese system of production in modules, and the idea that copying old masters was a good and illustrious way of learning to paint, the artistic value primarily depended on the complexity and accuracy of the scene and the high quality of painterly execution. Artists would use templates to shorten the production process, leading to near-identical scenes, but the disparity in accomplishment between painters is plain to see. (fig. 3) Painters could show off their personal artistic originality and creativity through their choices of brush size, colours, scene accessories and compositional elements, facial expressions, and so forth. Indisputably, the fusion of Western and Chinese painting conventions created a unique painting style; Chinese export paintings, with their multiple discourses and interdependencies, clearly shaped ambiguous understandings of what China meant, and means.

Dictated by the trade routes of the time, the westward movement of Chinese export paintings also conveyed images of China; the paintings became bearers of information. Notwithstanding the role played by Chinese painters in the creation of these images, the undoubted persuasive power of the illustrations was read and interpreted by the eye of the Western beholder. The various representations of ‘exotic’ Chinese subject matter appealed to a kind of immediacy and fascination. Despite the social use-value of Chinese export paintings offering ‘reliable’ evidence of a Chinese past, we can assume quite reasonably that the veracity of some subject matter is a more straightforward proposition, considered in terms of its likely commercial success. After all, the different themes represented only what Western customers demanded. They were in great demand and are still viewed by many people around the world as ‘articles of knowledge’. On the one hand, the subject matter of ‘daily life’ helps us to construct a ‘history from below’. They purported “in parallel with travel stories and personal diaries, to be eyewitness accounts of the city”, as Koon states, when she writes about the image of Canton that emphasised a hybrid Guangdong cosmopolitanism.9 On the other hand, it is acknowledged that the depicted scenes more likely distort social reality than reflect it.

Determining the gaze

For a long time, it was believed that a Chinese export painting’s use-value or utility resided in its ability to represent or reproduce reality. But we also know that these export commodities continued to sell like hot cakes even after their reliability as ‘witnesses’ was questioned later in the nineteenth century. The bright colours and the ‘exotic’ topics made the images all the more valuable. There is, then, the question of what Peter Burke calls “degrees of reliability” and “reliability for different purposes”.10

In the historical China trade period, the construction of visual culture included an array of agents who might have guided the gaze. By painting only specific subjects in their characteristic way, the painters themselves were important agents who guided the ‘trader’s gaze’, who in turn saw the paintings as a way to keep their memories of China afloat. In addition, both on board and on the home front, seamen and their wives were influential purchasing agents. The high status of Chinese art and the fashion during the period under discussion led to requests for, at least, a painting or an album to be brought back home. In addition to being a representation of a cultural reality, the paintings appear to form a selective reality, separate and distinct from the subjects they portray. It is clear that in the nineteenth century, and beyond, the paintings were, primarily, acquired and cherished not only for their historic and informative value, but also because of the longing for the exotic and romantic image of ‘the East’.

Today, the characters of the agents who determine the contemporary gaze on Chinese export paintings have changed, but they still exist. Think of descendants with their heirlooms as valuable antiques; auctioneers who determine which objects to put under the spotlight; art sellers with their targeted and compelling descriptions in catalogues and press releases; museum managers who decide what to exhibit; curators who digitalise and thus unlock, or on the contrary, lock their collections; enthusiasts who bring the paintings to the attention of a wider public via social media; and academics who write, or do not write, about this subject.

Back on the stage

The prospects for this painting phenomenon look good. On the one hand, revivification in the places where these paintings originated has resulted in an enormous demand for original paintings. We are seeing the newly established China trade museums and auction houses in China buy back these paintings from the places in Europe and America where they had travelled to in former days. By returning to China, new meanings will be created through this change in their cultural identity. Here, they can reassert their position as prestigious and identity strengthening commodities that confirm the cultural autonomy of owners; a use-value that, at the time of their production, was certainly true for most Western first owners. Thus, export paintings function as tangible evidential material of the early cooperation with overseas trading economies. Through today’s exciting developments in the art market, the paintings will become embedded in new shifting cultural contexts through time and space. In fact, we can say that they are in perpetual flux. Their spatial mobility with visible traces of their age, usage and previous life alter their meaning and use with respect to new cultural horizons.

On the other hand, times are changing and things are set in motion on the Dutch side. Museums have become more reflexive about nineteenth-century inheritances (“the nineteenth-century museum’s concern to develop an objective, systematic representation of the world as knowable by the Western subject”11 ) in considering the use of biography in and about the museum. Museum curators and collection managers increasingly view the long-overlooked status of Chinese export paintings and their confinement to difficult-to-access (fortunately, often well-acclimatised) museum storerooms as undesirable. Increasingly, they are seen as entwined with a museum’s biography. Biographical approaches to the understanding of Chinese export paintings with an accumulated experience that affords them their use-value “might inform current and future roles for the objects within the museum.”12 In recent years, some good practices have led to a major increase in the physical display of these objects that have not seen the light for years. The visibility of the paintings and, importantly, their connecting narratives upgrade this national cultural heritage in a meaningful manner. Moreover, an increasing number of online resources can be consulted today. Understandably, these developments make the author optimistic about increased accessibility to the material this article refers to. Their archival significance and their aesthetical beauty will amaze many. Likewise, their impact will help to dissolve the boundaries between the dichotomy of art that is ‘Western’ and art that is ‘Chinese’. Ultimately, they will create a relationship between visitors, the culture at large, and with future generations, either ‘here’ or ‘there’. Equally important, their visibility would put an end to the almost global unfamiliarity with the Dutch collections.

Stages of value assignment

1770-1870: Production period, exchange and consumption period.

The period of the making of. Transfer to other temporal and spatial settings, and different value accruement. High value/status in the Netherlands. Low value/status in China. 1870-1930: Exchange and consumption period. The period of emotional value accruement. Children and grandchildren inherit from father and grandfather; the stories behind the paintings are shared and known, the paintings are hung on walls.

1930-1960: Exchange and detachment period.

Great-grandchildren inherit from great-grandfather and taken the paintings to museums or for auction. Paintings frequently fall from grace. Period of decline of value.

1960-1990: Exchange and continued detachment period.

Low, ‘frozen’ status. Paintings offered for sale to museums or taken to auction. Paintings evaluated as poor quality objects and uninteresting, or even trash. Period of decline of value.

1990-2000: Detachment period.

Low ‘frozen’ status. No longer purchased by Dutch museums; still accepted as gifts. Status quo concerning value aspects. No particular attention (dormant).

2000-2016: Revivification.

Consumption and production period. Value re-accruement. Market improves. Paintings increasingly appear in auctions (consumers are producers at the same time). High status in China. Proliferation of museums and academic research centres. Chinese interest in the history of the historical China trade and the period of the Canton System (1757-1842). In China, these paintings are used to narrate these periods

Rosalien van der Poel, Head of Cabinet and Protocol at Leiden University, and research associate China, Museum Volkenkunde/National Museum of World Cultures (rhmvanderpoel@me.com).