Chinese dialect opera among the twentieth century Southeast Asian diaspora

From the early twentieth century, Chinese dialect opera [方言戏] troupes followed the movement of Chinese immigrants to the various ports and cities of Southeast Asia, a region that was oftentimes referred to by the Chinese as ‘the South Seas’ [Nanyang 南洋]. The travelling of the Teochew opera (the dialect opera mostly patronised by Teochew immigrants in Bangkok, Malaya and Singapore) and its films, from hometown Shantou to the Teochew diaspora in Southeast Asia, reveals the dynamics of Sino-Southeast Asian interactions, channelled through long-existing native-place ties. In the Cold War era, Teochew opera practitioners endeavoured to maintain their old native-place ties by designing new routes of travelling in order to circumvent tensions that had made Sino-Southeast Asian interactions almost impossible. However, in the ensuing period of nation building, Teochew opera faced more difficult struggles in choosing between the ‘national’ and the ‘diasporic’, because of its ‘unwelcome’ historical linkages with homeland China.

Pre-war demographic patterns and diasporic routes

Following in the footsteps of fellow countrymen, Teochew opera troupes left their home villages and embarked on long journeys to Southeast Asia. Their tour routes revealed a complex web of travel, underpinned by the distinct demographic patterns pertaining to the Teochew immigration in Southeast Asia. Bangkok was generally the first stop in Southeast Asia for Teochew immigrants and their opera troupes, who mostly originated from the region Chaoshan 潮汕.1 Firstly, Bangkok had the largest number of Teochew-Chinese, compared with other Chinese settlements in Southeast Asia. Such a sizeable Teochew diaspora in Bangkok made their hometown soundscape—the Teochew opera tours and performances—a daily supplement for people’s ritual and entertainment needs. Secondly, Bangkok was the entrepôt not only for trading, but also for cultural exchanges; from here the Teochew opera troupes were transported into the hinterland as well as the larger region of Southeast Asia.

Teochew settlements expanded further into the interior thanks to the completion of Thailand’s northern and southern railways. The improvement of transportation also greatly enhanced the mobility of Teochew opera troupes, meaning they could cross borderlands to places such as Indochina and British Malaya. Or they could opt for a much faster and easier itinerary by taking a steamship from Bangkok to Singapore. During the first half of the twentieth century, local diasporic conditions, such as the Teochew demographics in Siam/Thailand and improvements in transportation technology, determined the ways in which opera troupes conducted their tours transnationally.

Reaching out in the Cold War era

The Cold War cast a shadow over the established travelling patterns. Communications and interactions along the Sino-Southeast Asian migrant corridor became especially unstable due to the geopolitics in Asia. The Teochew opera, which had relied on the transnational tours, became entrapped in national/colonial frameworks that imposed their own political agendas onto the art form. In the opera’s place of origin Chaoshan 潮汕, top-down nationwide reform was enforced to turn the traditional folk practice into a diplomatic tool, intended to battle for the hearts and minds of the Chinese in Hong Kong and Southeast Asia. Teochew opera troupes were assigned with an important political mission: to bring reformed socialist art to Hong Kong in 1960. They were particularly successful, judging from the enthusiastic responses from the Hong Kong Chinese. The mission even stirred up a ‘feverish craving’ for Teochew opera, which brought about new business opportunities in the entertainment market of Hong Kong and Southeast Asia. Two CCP (Chinese Communist Party)-endorsed left-wing film producers in Hong Kong (New Union and the Great Wall) began to collaborate with the Mainland troupes, making seven Teochew opera films in all, between 1960 and 1965.2

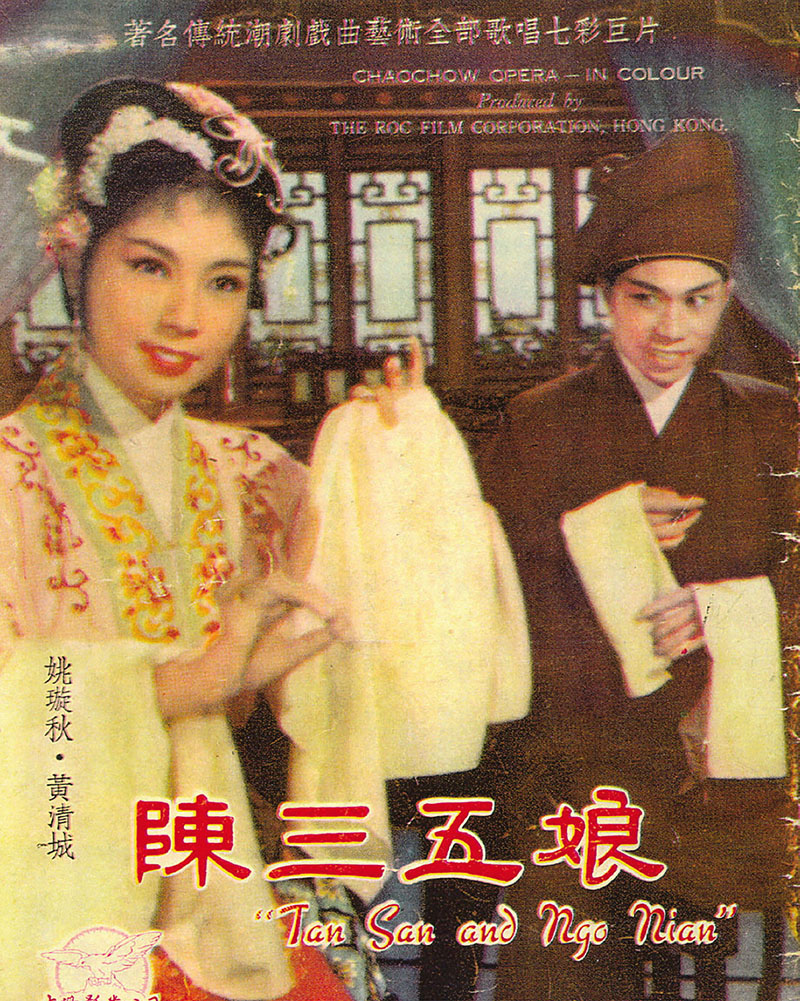

Front cover of promotion material accompanying the gramophone record for the 1962 Teochew opera film ‘Tan San and Ngo Nian’ (‘Chen San Wu Niang’ 陈三五娘).

The choice of Hong Kong as the first diasporic reaching-out was based on deliberate political and cultural considerations. Post-war Hong Kong was where East and West intersected, prospering economically and culturally as a result. As a British colony, Hong Kong was a gateway through which the PRC could disseminate its socialist propaganda to non-communist countries through the operations of Hong Kong’s left-wing filmmakers. In order to pave a smooth road for the circulation of left-wing opera films in Southeast Asia, different flexible strategies were developed so as to cover up the true identity of the film producers, or put in another way, to direct people’s attention away from the ideological underpinning in order to pass the film censorship.

The initial Hong Kong (filmmakers)—Mainland cooperation opened up such a lucrative market that many non-left-wing, and sometimes purported right-wing supporters, such as the Shaw Brothers, began to form transnational cooperations between Hong Kong studios and Southeast Asian theatres. These Teochew opera practitioners and filmmakers were constituents of the Shantou—Hong Kong—Southeast Asian operatic nexus. Their role as ‘cultural entrepreneurs’, moving between the PRC and the Southeast Asian market, was far more than that of mere intermediaries; they created their own cultural ventures by infusing the commercial dynamics that could only be bred in Hong Kong’s post-war society. So in the cultural arena, the political impasse of the 1950s and the 1960s was more imagined than real.

Caught between the ‘national’ and the ‘diasporic’

In addition to the gloomy atmosphere of the Cold War, struggles for independence and nation building were the priority of many Southeast Asian countries. Projects for national identity construction stood central, and exploring ways in which to use transnational opera tours to serve the national interest became popular. Singapore’s nation building in the 1970s and 1980s struggled to balance the de-territorial migrant history with the formation of a unified national identity. Chinese street opera (performed by troupes of Teochew, Cantonese, Hokkien and Hainanese operas) had integrated expressions of tradition, sub-ethnic ‘Chineseness’ and a de-territorialised diasporic practice. It thus became an embarrassing existential manifestation on the path to Singapore’s nation building and modernisation. The heritage-making of Chinese street opera brought about a more profound result of displacement. Specifically, the displacement took place both literally and metaphorically. In a literal sense, the physical displacement of the street opera performances from their original religious sites to designated spaces of the modern HDB (Housing and Development Board), Hong Lim Park, and lastly to indoor theatres. Partly as a result of, or parallel to, such a physical transformation, the displacement of the opera’s ‘Chineseness’ had a more far-reaching impact in a metaphorical sense, whereby identity and language had to be restructured for the sake of nation building. Rooted in the sub-ethnic dialect culture, Chinese street opera found itself uncomfortably framed in the national culture undergirded by the official ideology of multiculturalism and pragmatism. Such an irreconcilable gap between a traditional dialect culture and modern state ideologies determined the transient nature of Chinese operatic heritage-making, and it was eventually doomed to fail.

For opera practitioners, there was a more profound displacement of Chinese street opera as a diasporic livelihood and a de-territorialised living tradition. Unlike the state, which saw the heritage-making of Chinese street opera as a tool for nation building, opera practitioners saw it as the key to form their subjectivity: where they came from, who they were/are and why they held onto it. Their memories of the distant homeland in China and numerous places during their diasporic travelling were all contrary to what had been enforced upon them—a national belonging and identity that only restricted their diasporic mobility and endangered their livelihoods.3

Beiyu Zhang, Post-doctoral Fellow, Department of History, University of Macau, China. Her research interests include Sino-Southeast Asian History, Transnational Studies, Cold War History, Theatre and Performing Arts. Forthcoming publication: ‘Cantonese Opera Troupes on Sino-Southeast Asian Corridor: Nationalism, Movement and Operatic Circulations, 1900s-1930s’, Asian Reviews of World History (forthcoming in 2019). byzhang@um.edu.mo