China's relations with the Middle East: a perspective from the region

<p align=\"left\">After thirty years of domestic development and consolidation, China has entered a new phase in which its international aspirations are clearly pronounced; it is redefining its role in the international system. The Belt & Road Initiative (BRI) in particular signals a new type of regionalization in the making, with its bilateral projects with countries and regions beyond China’s immediate borders. One of these regions is the Middle East, where this realignment is intertwined with political and economic concerns.</p>

China’s relations with the Middle East were initially shaped by Cold War dynamics. While China did not intend to be actively involved in the region’s affairs, it took a stance within the framework of the ‘Third Worldism’ of the Mao-era. China’s relations with the Middle East were predominantly political during the Cold War period. Given China’s pro-Palestinian attitude, Egypt, a leading member of the Arab (Socialist) League, became the first Arab country to recognize the People’s Republic of China in 1956, while the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries in the West Camp refused to recognize it until Sino-US normalization in 1972. In return, China did not establish diplomatic relations with Israel until 1992. China recognized Palestine in 1988 with which it had maintained political, cultural and economic relations since the early 1960s.

Turkey also did not establish diplomatic relations with China until 1971. Turkey had received a high number of Uyghur refugees throughout the 1950s, following the consolidation of China’s borders. Consequently, Turkey served as one of the major hubs of the Uyghur diaspora in the following decades. The activities of the Uyghur diaspora leaders in Istanbul remained a source of discordance between the Turkish and Chinese governments even after the establishment of diplomatic relations. 1 In short, China’s relations with the Middle East until the 1980s were shaped by two factors: Cold War-era political rivalries and China’s own domestic security concerns. The post-Mao years would witness the centrality of economic motivations.

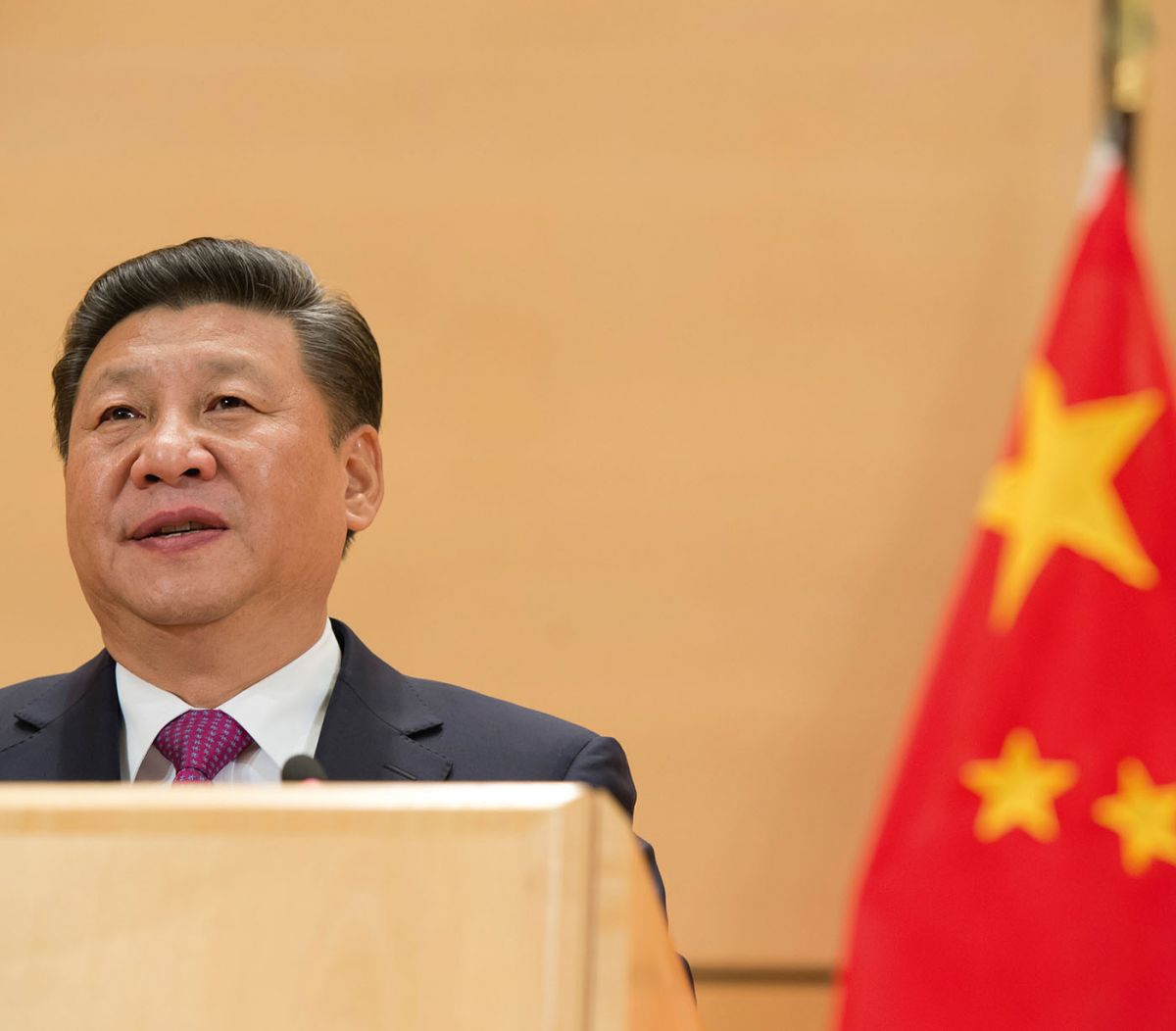

Currently, China’s relationship with the Middle East has three dimensions: Economic, international political, and domestic/regional security concerns. In assessing each of these dimensions, China’s uneasy relationship with the Middle East due to clashes of economic, diplomatic and security interests in the region can be highlighted. Japan and South Korea were the primary East Asian economic partners of the Middle East during the 1970s and 1980s. China slowly became an economic partner as its dependency on the region’s energy resources grew from the 1980s. China’s economic interests in the Middle East focus on four aspects: energy, trade, service labor, and the construction industry/investment. China has become an energy importer following the exponential growth of its industries. The Middle East supplies more than half of China’s oil needs and in return, China is the largest buyer of MENA oil. 2 Additionally, the Middle East is one of the central zones of the Belt & Road Initiative (BRI) of China launched by President Xi Jinping in 2013. BRI is the proactive foreign policy of China that aims at channeling out excessive domestic capital, creating employment for China’s skilled and unskilled workforce, and fostering bilateral interdependencies in Asia, Europe and Africa. The BRI includes the Middle East through major infrastructure investment policies, such as the Suez Canal, which is central to the ‘maritime Road’ part of the BRI. Israel and Iran are also included in the BRI: Iran through the Tehran railway that connects to the China-Pakistan route, and Israel through the Red-Med project that aims at connecting the Red Sea to the Mediterranean. Both railway projects are central to the ‘land-bound Belt’ part of the BRI. The BRI is primarily based on the construction industry, as exemplified in Kuwait’s Silk City. 3 China’s infrastructure investment in the construction industry is a welcomed development against the economic slowdown Arab countries have been facing following the political instability in the aftermath of the Arab Spring or dropping oil prices. 4

Besides these economic motivations, China appears willing to be involved in regional political affairs as a tool to consolidate its image as a responsible world power. China’s traditional foreign policy doctrine, Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence, formulated in 1953, upholds non-intervention in the domestic affairs of sovereign states. Such an approach prevented China from getting involved in regional conflicts as a moderator or an external actor that could change the balance of power. However, China has recently made moves signaling a more proactive foreign policy. In the Arab-Israeli conflict, China maintains its position of advocating a two-state solution as manifested in the 2016 Arab Policy paper. 5 However, Chinese academic and cultural institutions also do not participate in the boycott against Israel, which makes China a welcome candidate for mediation between the two parties.

As for the Syrian civil war, China has been following international institutional channels such as the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) and the International Syria Support Group, and has acted as Special Envoy in the Syrian Peace Talks following Russia’s proposals. Therefore, China is perceived as a part of a coalition with Russia and partly with Iran on the Syrian peace process. 6 The reason that China does not act more forthcoming regarding the Syrian crisis is due to the outcome of the Libyan civil war during the Arab Spring period. China did not object to the UNSC resolution to intervene in the Libyan civil war but when the intervention caused the overthrowing of the Qaddafi regime, China felt its main foreign policy principle, non-violation of state sovereignty, had been compromised. 7

Turkey is currently ambivalent about China’s position in the Syrian crisis, although it previously collaborated in a military drill with China in 2010 on the condition that Israel be excluded. The military drill was followed by a missiles deal with China which was abruptly and unilaterally canceled by Turkey in 2014 in response to NATO’s protests. 8 Prospects for a closer alliance with China and membership to the Shanghai Cooperation Organization are often pronounced by the current Turkish government as a sign of its new multifaceted, less Western-oriented, foreign policy orientation. 9 In short, China is gradually emerging as a global power involved in regional affairs.

While China appears willing to act as a responsible global power, its own domestic security concerns prove its involvement in the Middle East region to be less than smooth. There are two main domestic concerns that shape China’s involvement in the Middle East: Middle Eastern relations with the Uyghur minority in China, and the impact of the Arab Spring on China’s public opinion. China’s relations with Turkey have followed a tumultuous path given the former’s soft attitude towards the Uyghur separatist movement. While the movement’s headquarters were removed from Istanbul following the Turkish government’s ‘China pivot’ in the early 2000s, 10 China is concerned that there is an increasing number of Chinese nationals of Uyghur background joining ISIS in Syria with the intention to go back to China via Turkey. 11 Consequently, China imposes visa restrictions on Turkish nationals even though China and Turkey enjoy warm relations at the presidential level, as demonstrated in the 2014 G-20 Summit in Hangzhou where Turkish president Erdogan was a keynote speaker along with Russian president Putin.

China’s approach towards the popular protests in Iran and the Arab Spring has been cautious, as it perceives these popular protests against governments to be detrimental towards China’s domestic stability concerns. However, China’s reluctance to take a stance against the Arab regimes during the Arab Springs led to a loss of credibility for the country in Arab public opinion. 12

To conclude, China has been heavily involved in Middle Eastern affairs in recent years. While its economic involvement is welcomed by the regional actors, political and security concerns create obstacles for China to be perceived as a global power central to regional affairs in the Middle East.

Ceren Ergenç, Assistant Professor, Middle East Technical University, Department of International Relations & Asian Studies Program, Turkey cergenc@metu.edu.tr