China at UN COPs: COP26 recap and COP27 forecast

As the 27th session of the UN Conference of Parties (COP27) approaches, this article looks back the progress China made at COP26 and foresees what to expect from China for COP27. COP26 was considered a ‘big year’ in the UNFCCC-led multilateral process to combat climate change. Six years after the signing of the Paris Agreement, it was time for states to make real actions on meeting our climate target by keeping the temperature rise this century below 2 degrees. The outcome of the negotiation indeed made some progress. However, it still fell short of meeting the 1.5-degree target set by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Chang (IPCC). China, as a major player in this multilateral process, has a role in determining how far we can go with our climate actions. The policies and statements made by China before and during the COP26 not only contributed greatly to the negotiation process, but also signified certain changes and innovations in China’s domestic climate governance system.

China’s participation in COP26 in Glasgow did not disappoint. China’s positions at COP26, as one of the most powerful players in the UN-led multinational climate talks, revealed both goals and reservations. While COP26 highlighted the gap between what developing countries can demand and what industrialized countries could deliver, China’s participation appears to be even more critical in deciding the success of such efforts. China has made significant and ambitious carbon emission reduction targets in front of the international community. Nevertheless, these commitments are circumscribed by the need to balance politics at home and China’s wider foreign policy agenda. This essay examines China’s new commitments at COP26, emphasizing not just the significance of these climate policy efforts at the international level, but also the wider challenges at the domestic scale to promote decarbonization.

China at COP26: ambitions and reservations

China has entered a new era of dual carbon targets since President Xi Jinping announced the country’s new climate targets in 2020. Its main goal is to reach carbon peak in 2030 and carbon neutrality in 2060. China has already implemented several initiatives at home in the run-up to COP26 in Glasgow, demonstrating its commitment to tangible climate action. During the month of October in 2021, China issued multiple reports and policy papers stating their climate related agendas, 1 which included working guidance and action plans for carbon peaking, and China’s 2021 yearly response to climate change. 2 On top of that, on the 28th, the Chinese government presented their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) and long-term low-carbon development strategy to the UNFCCC secretariat. These five new policy documents announce China's decarbonization plans to the rest of the world, as well as the country’s position on climate debates at both international and domestic levels.

COP 23 in Bonn (Photo by the author, 2017).

The joint Glasgow announcement between China and the United States on enhancing climate action in the 2020s was undoubtedly significant in boosting global climate objectives. Both countries pledged to further prioritize climate action in the 2020s, highlighting their shared conviction in reducing carbon and methane emissions while also reaffirming their commitment to the Paris Agreement. 3 Being the primary movers of international climate negotiations, these two countries have put aside their differences on many other issues to reaffirm their commitments and actions in addressing climate change. In so doing, the world has a fighting chance of retaining the goal of keeping 1.5C warming limit within reach. 4

At COP26, China has also promised to gradually reduce coal usage. First, China’s president, Xi Jinping, announced to the world China’s 30/60 dual carbon targets in 2020, which stated China’s intention to peak carbon emissions by 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality by 2060. Then, just days before the COP26, he announced at the UN General Assembly that China will stop building new coal power plants abroad, in response to criticism that China is outsourcing carbon power plants through its Belt and Road Initiative’s overseas infrastructure projects. Notwithstanding such apparent progress, other considerations led China to resist over-committing to climate mitigation measures. For example, China was instrumental in changing the language used in the Glasgow agreement on coal power from “phase-out” to “phase-down.” Even though high-level authorities set the ambitious goals and stated that “coal usage will be gradually reduced over the 15th Five-Year Plan period (2026–30),” China did not sign the Global Coal to Clean Power Transition Statement produced at COP26. The statement is a key agreement for phasing out coal power and was signed by 46 countries. 5 As the world’s largest coal power generator, China’s refusal to accede to the language of “phasing out,” and instead opting for “phasing down” coal demonstrates the tensions in climate mitigation measures and broader developmental objectives. Thus, climate policies reflect the careful balancing act between ambitious worldwide aims and a gradualist approach towards energy transition at home.

China also joined the Glasgow Leaders’ Declaration on Forests and Land Use, 6 a statement aimed at halting forest loss and degradation. China also expressed its support for ending deforestation and enforcing laws against illegal importation of deforestation-risk commodities in a joint statement with the United States.

In general, the international community expected China to demonstrate greater climate ambitions and leadership at COP26, and China did so in certain areas while expressing reservations in others. This suggested that the country has reached a critical juncture in the period of “30/60 dual carbon targets,” where both possibilities and problems exist.

“1+N”: new governance scheme at home

Since the release of the dual carbon targets in 2020, China has failed to provide a clear roadmap that can link domestic economic development with its climate targets. The public was then presented with a new governance plan, which was released in the run-up to the COP26.

The “1+N” policy framework represents China’s new climate strategy while also providing a clear path for different sectors to follow in order to meet China's dual carbon targets. China’s emission-peaking efforts will be spearheaded by a newly constituted working group on climate change led by Vice Premier Han Zhen and consisting of high-ranking officials. 7 Wang Yi, a member of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress and vice president of Institutes of Science and Development at the Chinese Academy of Sciences further clarified in a side event at COP26. He said that this top-down design emphasis on strategic guidance from the top leaders in China, the “1” stands for the working guidance for achieving the dual carbon targets; and the “N” comprised of several policies being enforced, such as the carbon peaking action plan before 2030, policy measures and actions on key areas and industries, and any forthcoming plans to facilitate the efforts. The overarching policy framework aims to lead efforts in several areas, such as the energy system, circular economy system, commerce, transportation system, and so on, in order to gradually transition to carbon neutrality. Specific plans and targets have been drafted for each policy area. Furthermore, the framework emphasizes the implementing subjects, which include ministries, commissions, local governments, industries, industrial parks, corporations, and individuals.

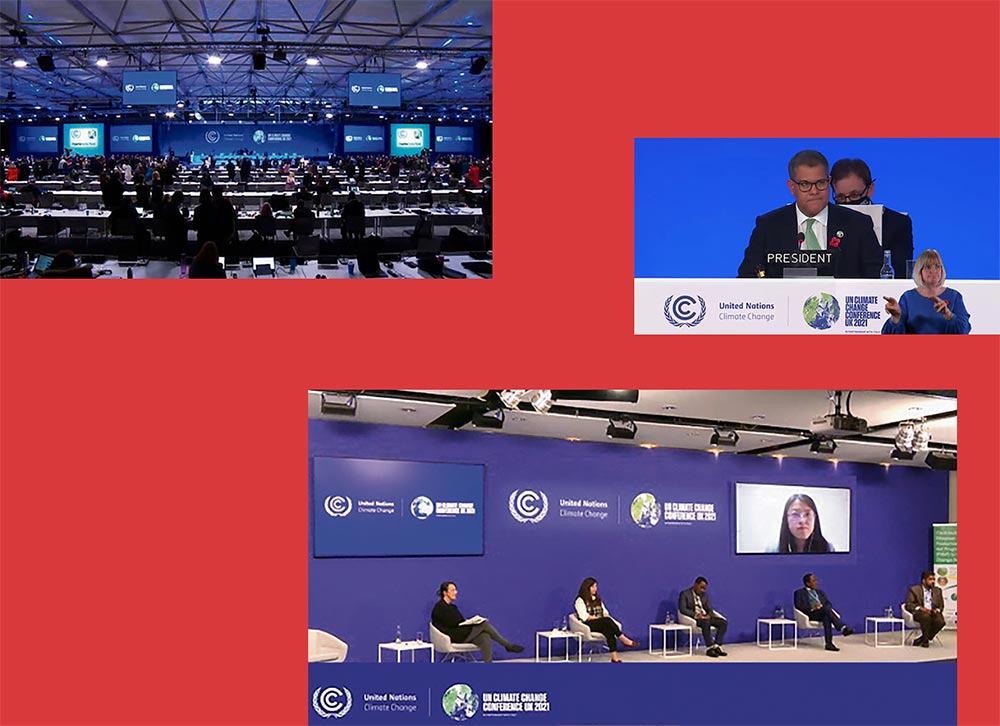

Impressions of COP26 in Glasgow (Photos courtesy of Greenovation Hub, 2021).

The “1+N” outlines a path for China to effectively achieve its climate goals while also creating synergies at all levels and across sectors. It addresses both short- and long-term climate goals, requiring contributions from a wide range of players across all key emitting industries and related spheres. For instance, according to the Plan, the energy system will limit coal consumption and transform the power system to be based on new energy. 8 In the meantime, the emission-intensive steel industry is targeted to reach carbon peak earlier than 2030 under the new guidance. Apart from the five above-mentioned policies that solely focused on climate governance, the Chinese government introduced several key policy documents in the year leading up to the COP26. The 14th Five-Year Plan for national economic and social development, the long-term goals for 2035, and the 2021 report on the work of the government all discussed the blueprint for China's future climate targets and laid the foundation for the “1+N” framework. This new policy framework is aimed at setting the direction for China’s green transition and providing more systematic political guidance on China’s environmental governance from top-level leaders. Just like Wang Yi pointed out, “to meet the targets, we have detailed a transformation to our entire system, not only in the energy sector, but across society and the economy.” 9

COP27 forecast obstacles and possibilities

Despite the commitment to actual climate targets and initiatives, China continues to face domestic concerns, as evidenced by the delicate balance displayed at COP26. In China, coal power plants are still a key source of energy. Concerns have been voiced over whether the plan to restructure the coal industry can keep up with the country’s accelerating economy, as shown by the power deficit in Northern China in late 2021. Short-term volatility can make long-term planning and goal achievement difficult. China’s officials have made up their minds to keep the country on a low carbon path. However, keeping 1.5 degrees Celsius within reach will require their government to guide the process while carefully maintaining the delicate balance between economic development and decarbonization.

Furthermore, bilateral climate negotiations between the US and China have been put on hold due to the continuing conflict over Nancy Pelosi, the Speaker of the US House of Representatives, visiting Taiwan. The cooperation between the two largest emitters in the world is thus once again precarious, which might make negotiations at the upcoming COP27 even more challenging. However, even though the geopolitical conflict temporarily halts climate cooperation between China and the US, if the two nations can commit to other multilateral and regional agreements, it may still be possible to continue making progress against climate change. This may be a crucial factor in the success of the COP27.

Nonetheless, China’s low-carbon transition appears to be a difficult assignment from every angle. The global response to climate change has been hampered by obstacles such as the public health crisis, the blockage of multilateralism, and an increase in economic and trade frictions. China’s climate pledges boosted global climate efforts, and the “1+N” policy framework demonstrated seriousness about delivering such climate pledges ahead of COP26, 10 but strong political will still needs to consider domestic realities and challenges in order to make concrete progress and a successful international contribution.

Hao Zhang is a PhD candidate at the International Institute of Social Studies (ISS), Erasmus University Rotterdam (EUR). Before joining ISS, she was a master’s student majoring in international affairs at School of Global Policy and Strategy at University of California, San Diego. Her current research focuses on policy advocacy of Chinese NGOs in global climate governance. Her research interests lie in global climate politics and diplomacy, and NGO development in China. E-mail: h.zhang@iss.nl