Chaekgeori: the power of books

<p><em>The Power and Pleasure of Possessions in Korean Painted Screens</em><br>Showing at the Charles B. Wang Center, Stony Brook University until 23 December 2016<br>Spencer Museum of Art at the University of Kansas (8 April–12 June 2017)<br>Cleveland Museum of Art (5 August–5 November 2017)</p>

The exhibition The Power and Pleasure of Possessions in Korean Painted Screens explores the genre of Korean still-life painting known as chaekgeori 冊巨里 (loosely translated as ‘books and things’). Chaekgeori [Check-oh-ree, 책거리) was one of the most prolific art forms of Korea’s Joseon dynasty (1392–1910), and it continues to be used today. It often depicts books and other material commodities as symbolic embodiments of knowledge, power, and social reform. For the first time in the United States, more than twenty screen paintings dating from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries of the Joseon dynasty are on view at the Charles B. Wang Center at Stony Brook University in New York.

Curated by a group of Korean art experts that include Byungmo Chung (professor, Gyeongju University), Sunglim Kim (professor, Dartmouth College), Jinyoung Jin (Director of Cultural Programs, Charles B. Wang Center), Sooa Im McCormick (Assistant Curator of Asian Art, Cleveland Museum of Art), and Kris Imants Ercums (Curator of Global Contemporary and Asian Art, Spencer Museum of Art), this collection showcases marvelous and rare examples of chaekgeori screens alongside the works of a diverse body of contemporary artists who continue this genre into the twenty-first century. Seven contemporary artists featured in the exhibition are Stephanie S. Lee, Seongmin Ahn, Kyoungtack Hong, Patrick Hughes, Sungpa, Young-Shik Kim, and Airan Kang.

Initially intended as a means to maintain and promote the disciplined Confucian lifestyle of Joseon Korea against an influx of ideas and technology from abroad, King Jeongjo (1752–1800, r. 1776–1800) encouraged court painters to emphasize books as the main subjects of royal screen paintings and to embrace the power of books and the ideas contained within them. Realizing that books were vehicles of change in his society, King Jeongjo worked hard to popularize the idea of books as symbols able to transcend the tangible originals among Korea’s artisans and other elites. In the process, the value of physical books actually increased and became highly sought-after. This desire for books and other commodities in Korea set in motion a significant social and cultural shift toward materialism that has continued into the twenty-first century. One can say that chaekgeori paintings not only have the ability to teach and inspire, but they also possess the power to shape the values of a society.

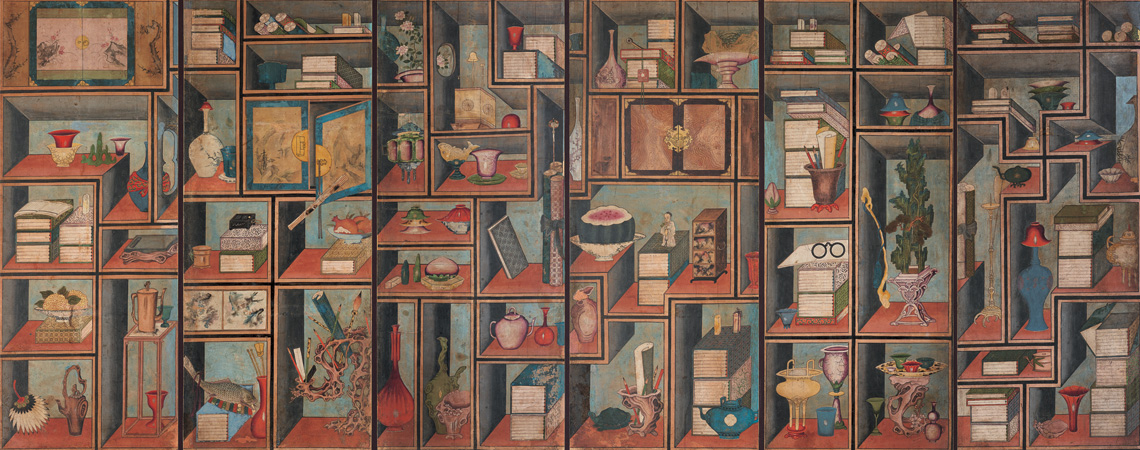

One masterpiece in the exhibit serves as a great example of this. The piece in question is a six-panel screen that has a distinct rhythmical balance in its composition, depicting a full stack of books and luxurious objects (fig. 1). Chinese curiosities from the Qing dynasty (1644–1912) flooded the homes of the upper classes of Korea during this period, and this is reflected in this screen. Books mingle with scholarly objects (such as imported Chinese ceramics, brushes, paper, eyeglasses, and the like), all competing for prominence of place and the attention of the viewer. Each section elegantly displays scholarly accoutrements and prized collectibles, often in the shape of or featuring images of auspicious symbols. These images together signify the hope for academic achievement, social advancement, longevity, the birth of many sons, and happiness. The screen also utilizes European linear perspective, trompe l’oeil, and shading effects to create the illusion of three-dimensional space.

The flexible yet timeless themes chaekgeori emphasizes and the numerous possibilities and techniques it can utilize have ensured the genre’s ongoing popularity, now stretching for more than two centuries. No other genre or medium in Korean art, in both literati and folk painting, has so engaged and documented the image of books and collectable commodities, and the changes in how we view and value them over time. And when the genre transitioned into folk-style painting, new and unexpected visual elements emerged. Folk-style chaekgeori expanded the range of subjects beyond books to express surrealistic dreams and more. For example, an unusual feature of this particular late nineteenth-century screen (fig. 2) is its depiction of clouds and a dragon. The dragon symbolizes the desire for many sons, the wish to educate them, and the hope to have them improve their social status through education. The surrealistic depictions of such earthly desires is a testament to the incredible imagination inherent in folk-style chaekgeori.

The exhibition also showcases how this artistic genre has been utilized by today’s artists. For example, in Airan Kang’s Digital Book Project installation, books glow, catching the viewer’s eye, yet they simultaneously invite and forbid access as embodiments of ideals (fig. 3). This aspect of her work can be directly compared to the representation of books in chaekgoeri paintings, where books are symbols of ideas, inaccessible objects that ultimately surpass their original, physical meaning and being. In our increasingly paperless and digitized society, Kang depicts books as still holding an inner light, an artistic decision which seems to be an argument against the practice of valuing books solely as material commodities.

In his Library series, Kyoungtack Hong paints still-lifes filled to the brim with books, birds, and plants. The results are often surrealistic with materialistic overtones. Whereas in traditional chaekgeori paintings objects take on a privileged aura, in Hong’s paintings the materials of old—Chinese ceramics, fabrics, lacquered boxes—yield to plastics, mass-produced disposables, and impersonal objects. In his Library 3 (fig. 4), thousands of books serve as space defining objects, backgrounds, and pedestals for hundreds of mass-produced toys. These toys, due to sheer quantity and our preconceived notion of their value, are ultimately of little importance. On the left side of the painting, three skulls enter the pictorial space. Symbolizing death, they are a stark contrast to the durable plasticity of the toys, as if to forecast an impending doomsday. On the right side, the Virgin Mary acts as a quintessential (yet also ironic) representation of Western religion, ethics, and humanity. Through these juxtapositions, Hong reminds his viewers that there is more to life than the ownership of uncountable objects, especially when said objects are so empty of any transcendental value or meaning. Books are in the background of our lives, much like in Hong’s painting, serving as props for materialism. Using chaekgeori, Hong is able to astutely critique this state of affairs. The other modern artists featured in the exhibition make similar (yet also differing) commentaries on these themes, using a genre created and promoted expressly to combat against materialism.

The significance of any work of art consists largely in the work’s ability to carry and communicate embodied meaning. And when it comes to documenting, engaging, and commenting on the culture of consumption, no other genre or medium in Korean art can compare to chaekgeori. By drawing on a long artistic lineage and making comparisons to the traditional form and objectives of chaekgeori with contemporary examples, The Power and Pleasure of Possessions in Korean Painted Screens facilitates a better understanding of the intellectual curiosity and the desire to own commodities that animated Korean society then and that continue to animate us now—and how these powerful urges continue to be portrayed in art.

Jinyoung Jin (Director of Cultural Programs, The Charles B. Wang Center)