Beyond diplomacy. Japan and Vietnam during the 17th and 18th centuries

<p align=\"left\">Compared to ample studies of the history of Japan’s foreign relations with China, Korea, Ryūkyū and the Ainu people, there is little research available concerning the history of Japan’s relationships with Southeast Asia. This article provides a short sketch of Japan’s relations with Vietnam in the early modern period by focusing on international trade and diplomacy, and will hopefully serve as an initiator for further research.</p>

Tokugawa Japan (1603-1867; also known as the Edo period) set in motion a unique systematic policy for foreign trade and diplomacy with the establishment of the so-called sakoku isolationist policy in the 1630s, which continued until the 1850s when Japan signed the treaty to open ports for trade to Western countries such as Great Britain and the United States of America. The sakoku policy limited international trade to four gateway ports: Tsushima, Matsumae, Satsuma and Nagasaki.

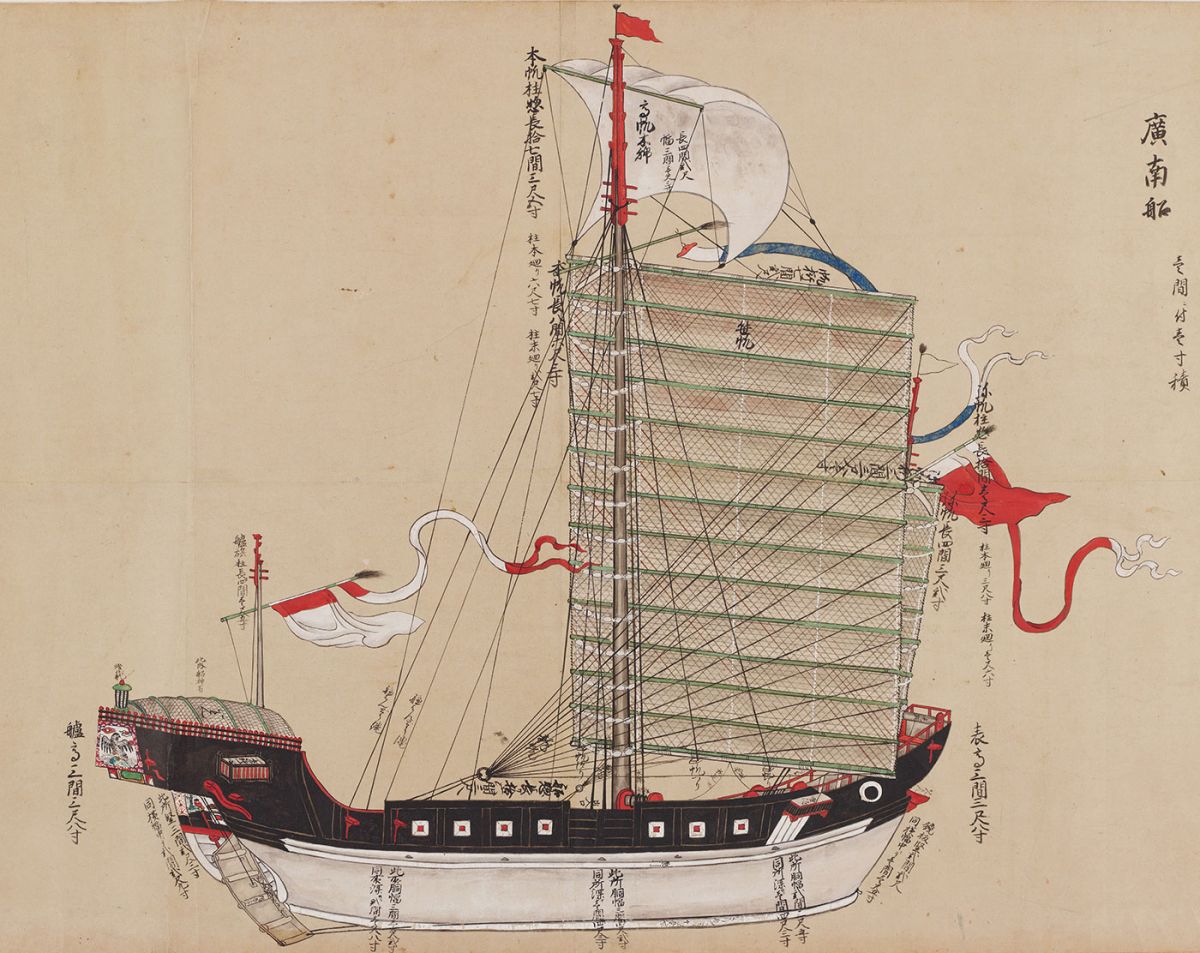

The first three gateway ports were each managed by a han [clan] under the supervision of the Tokugawa central government. Tsushima was assigned to manage foreign relations with the Kingdom of Chosŏn (Korea), Satsuma took care of affairs with the Kingdom of Ryūkyū (present-day Okinawa), and Matsumae interacted with the Ainu people on the island of Hokkaidō. The port of Nagasaki was an exemption. This gateway was managed by the Governor, appointed by the Tokugawa central authorities, and it was the most important gateway port in terms of the scale of foreign trade. Only two types of vessels were permitted to call at this port: those of the Dutch East India Company (Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie: hereafter VOC), and tōsen [junk ships]. Literarily meaning ‘Chinese ship’, tōsen came in many varieties. During the 17th century in particular, several sorts of junks berthed at Nagasaki: junks from Taiwan under the control of Zheng Chenggong (Koxinga), who attempted a revival of the Chinese Ming dynasty; junks from Chinese coastal areas under the control of Qing China; and junks from ports in Southeast Asia, which were run and managed by overseas Chinese merchants.

While Tokugawa Japan officially continued to keep diplomatic relations only with Korea and Ryūkyū, Japan held a multi-directed foreign trade policy, realized through these four gateway ports, not only with Korea and Ryūkyū but also with other countries such as China, Southeast Asian states and the Netherlands. Thanks to several sorts of junk ships coming from the China Sea region, Japan successfully obtained a set of Asian commodities, such as raw silk and sugar, at reasonable prices without sending out its own Japanese vessels to China and Southeast Asia.

Japan’s trade with Vietnam

Before the establishment of Japan’s sakoku isolationist policy in the 1630s, Vietnam’s trade with Japan was mainly conducted by Japanese merchants holding the so-called ‘red-sealed letters’ provided by the Tokugawa shōgun’s central authorities. But after Japanese nationals were banned from going abroad by Tokugawa central authorities in 1635, international trade between Japan and Vietnam began to be run by overseas Chinese settled in Vietnam in cooperation with Japanese immigrants living there, and who best knew the conditions of the Japanese market. In addition to overseas Chinese traders in Vietnam, the VOC conducted trade between Japan and Vietnam under the framework of the intra-Asian trade.

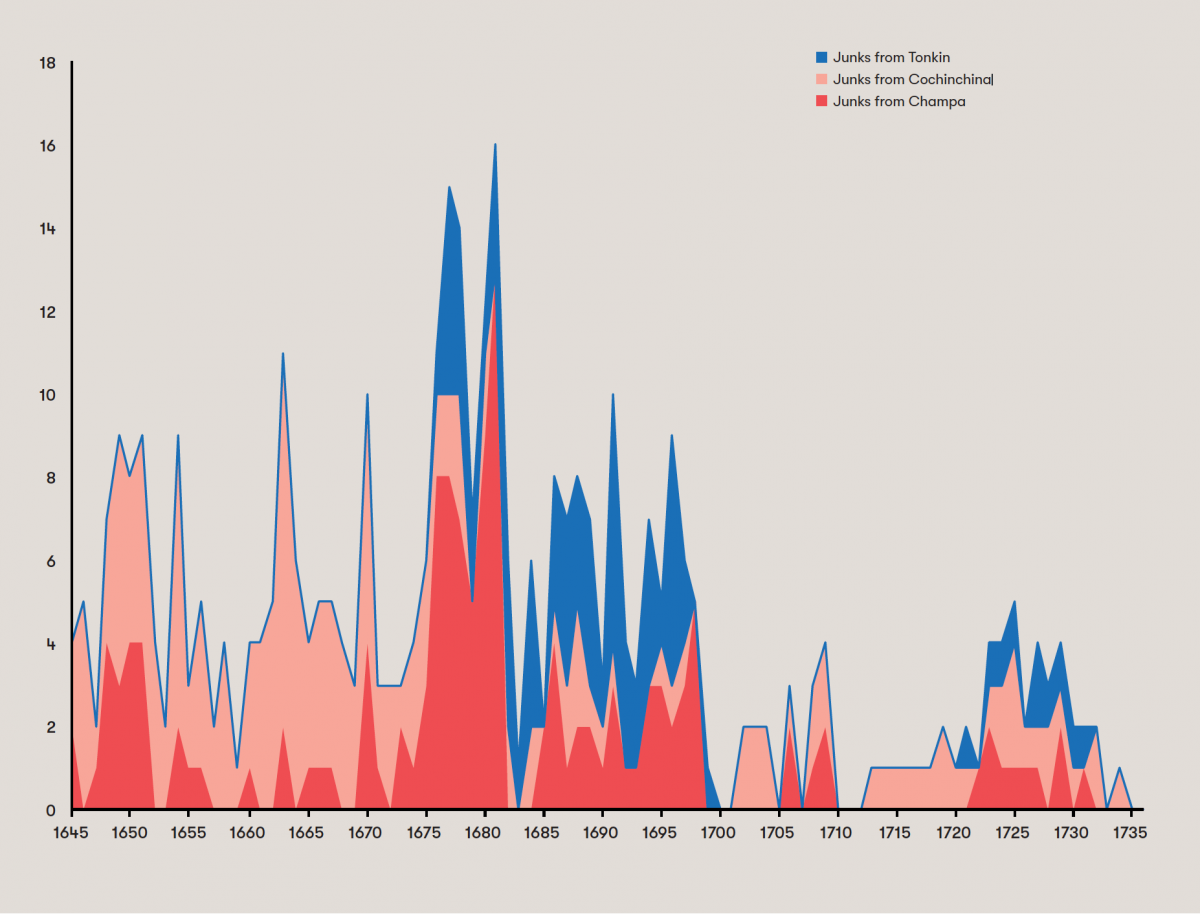

The Japanese categorized junk ships from Vietnam according to their place of embarkation. The first category was the ships that came from Tonkin (present-day Hanoi) in Northern Vietnam, which was the capital of the Trịnh regime. The second category was called Kannan (or Kannam), and were ships originating from the middle of Vietnam, for example, from the port city of Hoi An, formerly known as Fai-Fo or Faifoo. These ships were under the control of the Nguyễn regime. The third category covered junk ships from Champa, south of the territory of Nguyễn Cochinchina.

The international division of labor was a basis for this maritime trade. As direct trade between Japan and mainland China had come to a halt following the maritime ban in Ming China (1368-1644), Vietnam came to be regarded as a substitute source of raw silk for the Japanese market. Vietnam also exported cinnamon, several types of sugar, aloeswood (used in incense and perfume), rayskin, and animal hides (deer, buffalo, etc.) to Japan.

Silver was the most significant trading item from Japan to Vietnam. In addition to silver, copper bar and copper cash were also exported from Japan to Vietnam. Japanese copper was smelted in Vietnam and used to manufacture guns and other weapons; some of the copper cash was in circulation as a small denomination currency in Vietnam. Miscellaneous goods such as lacquerware and house utensils were also shipped to Vietnam from Japan.

The VOC was also engaged in the Vietnamese trade, where it maintained trading posts in Tonkin and Cochinchina. The Vietnamese trade was important for the Dutch Japan trade; in order for the VOC to acquire large volumes of silver in Japan, it needed Asian products for the Japanese market. Trade between Japan and Vietnam was done under the framework of the VOC’s intra-Asian trade: by supplying Southeast Asian goods to Japan, the VOC obtained silver and copper from Japan and then sold Japanese copper in South Asia, where it could procure Indian cotton textiles for the market in Southeast Asia. Through this triangular trade in Asian waters the Dutch company was able to reduce silver exports from the Netherlands to purchase Asian products such as spices for the European market, and to ultimately obtain large profits.

The rise of the Chinese junk network

In the late 17th century, the economic links between Japan and Vietnam began to decline. There were various reasons, including the Ming-Qing transition, the arrival of political peace in China and the recovery of the Sino-Japan trade. After the surrender of the Zheng family in Taiwan (Kingdom of Tungning; 1661-1683) to Qing China, the trading pattern of junk traders changed on a large scale around the China Sea region. Until 1683, most junk traders had been overseas Chinese settlers in Vietnam. Some of these overseas Chinese were merchants and some were junk ship crew members. Afterwards, more Chinese junk traders from mainland China began to participate in the Vietnam-Japan trade. In 1692, for example, 45 Chinese and only 6 Tonkinese were registered on a particular junk ship from Tonkin to Nagasaki.

But then, due to the rapid increase of the numbers of Chinese junk ships coming from the Yangtze River Delta in the 1680s, Japan undertook to restrict the volume of international trade. And so, in 1715, the Shōtoku Shinrei Act was issued by the Japanese Tokugawa central authorities. This act introduced a new restriction policy for international trade, and the pattern of maritime trade by junk ships began to change again in the China Sea region. From 1715, to around the 1760s, Vietnam trade with Japan was conducted only by Chinese traders based in ports around the Yangtze River Delta, such as Zhapu and Shanghai. They departed from ports in the Yangtze River Delta, headed to Vietnam to procure Vietnamese goods for Japan, and shipped onwards to Nagasaki. Copper purchased in Nagasaki was sold in mainland China. However, during the 1760s, Vietnamese products became widely available in the Yangtze River Delta, and so Chinese junks for the Japan trade no longer needed to travel to Vietnam. In fact, the last junks to sail to Nagasaki (according to VOC records) from Tonkin and Cochinchina did so in 1763 and 1767 respectively, and from Champa already in 1735.

This change in the pattern of junk ship trade was not only seen between Japan and Vietnam, but also generally for the junk trade between Japan and other Southeast Asian ports, such as Ayutthaya and Batavia. By and large, the junk trade at Nagasaki became dominated by mainland Chinese traders from the Yangtze River Delta, where Southeast Asian products were extensively available thanks to the development of the Chinese junk trading network around the China Sea region.

Diplomatic relations with Korea, China and Vietnam

Unlike with Korea, Japan refrained from official diplomatic relations with the states in Southeast Asia after Japan’s establishment of the sakoku isolationist policy in the 1630s. For example, when Thai King Narai took the throne of the Kingdom of Ayutthaya in 1656, he sent a mission to Japan with his official Royal letter addressed to the shōgun. In this letter King Narai expressed his wishes to reopen diplomatic relations with Japan in order to further develop the international trade between both countries. In spite of the King’s eagerness, the Tokugawa central authorities refused his request.

By contrast, the Tokugawa central authorities did choose to reopen diplomatic relations with Korea in 1607, when the Tokugawa central authorities accepted a Korean mission to Edo (currently Tokyo). Japan’s new political regime of Tokugawa shōgunate was intent on putting an end to the awkward atmosphere between Japan and Korea after the Japanese invasions to Korea led by Toyotomi Hideyoshi in the late sixteenth century (1592-98). From 1607 to 1811 Korean official diplomatic missions to Japan amounted to twelve. Except for the last mission in 1811 to Tsushima island, all other missions arrived at Edo and contributed to the establishment and preservation of peace between the two countries, even in the eighteenth century when Japan-Korea international trade had declined. Interestingly though, this foreign relationship was somewhat strange because it lacked a full exchange of missions; the Tokugawa central authorities never sent a diplomatic mission to the capital city of Korea. This was likely due to the simple fact that Korea feared a Japanese visit could lead to a repeat of a Japanese invasion.

The Tokugawa central authorities also never established official diplomatic relationship with Qing China. If negotiations were necessary between these two countries, for instance, when castaway people were sent back to Japan from China, local governors or officers would just exchange letters.

Vietnam was also ‘rejected’; in 1688, the King of Cochinchina sent an official letter to the shōgun to ask for copper cash from Japan, yet the Tokugawa central authorities never sent an official letter back to Vietnam. However, while the Tokugawa central authorities did not wish for official diplomacy, they did want to maintain positive practical relations, for example, through the Governor of Nagasaki. In other words, Japan continued to make an effort to keep peaceful links with Vietnamese states without an official relationship at the top levels. For example, the King of Cochinchina sent a letter to the Governor of Nagasaki in 1695 to show his thankfulness for sending Vietnamese castaways back from Japan. These Vietnamese castaways were secured by a Chinese junk ship going to Nagasaki and they were sent back from Nagasaki to Cochinchina under the supervision of the Japanese Governor of Nagasaki. Another example took place in 1795; seventeen Japanese castaways discovered on the Vietnamese coast were brought back to Nagasaki by a Chinese junk ship.

Links between Japan and Southeast Asia

In terms of trade, there was clear competition between various traders. The VOC competed with several Asian indigenous traders. Among Asian traders, Chinese junk traders were dominant, although Chinese traders were not a single monolithic group. Each Chinese junk trader group emerged and declined in the course of time. Through these processes, a well-organized Chinese junk trading network was established in and around East Asia and Southeast Asia. The development of these trading networks and the competition among traders contributed to the efficient economic development in the China Sea region. Further research on trade and diplomacy shall help us paint the whole picture of economic change in East Asia and Southeast Asia in terms of the international division of labor.

One final remark on conducting further research is that it will entail a multi-archival method. Japanese and Chinese records are extant; especially local archives at Nagasaki offer detailed information. However, historians benefit hugely from consulting the archives of the VOC. This company was a key trader, and connector of Southeast Asian states, China and Japan. Dutch records provide historians not only with detailed information about the company, but also concerning its competitors, because this wise merchant company was highly sensitive to the activities of its rivals.

Ryuto Shimada, Associate Professor, Department of Oriental History, Faculty of Letters, The University of Tokyo (shimada@l.u-tokyo.ac.jp).