Between Freedom and Poverty: The ‘River Gypsies’ of Bengal

In Bengal, today the Indian union state West Bengal and Bangladesh, the so-called ‘Bedes’ are perceived to lead an itinerant way of life and hold ‘exotic’ occupations. This reputation has attracted the attention of Bengal’s sedentary population and stimulated the imaginations of many authors and poets who often portray the ‘Bedes’ in a highly romantic manner. In English, ‘Bedes’ are commonly referred to as ‘Gypsies’ or ‘River Gypsies.’ Similar to the European ‘Gypsies,’ their women often attract more attention than their men. This article will focus on the reasons for this circumstance and will deconstruct such erroneous but widespread portrayals.

The Bengali term bede and its various variants (e.g., bādiẏā, bediẏā, and bāidyā) are in themselves highly problematic; for this reason, I write ‘Bede’ in single quotation marks when I refer to the people who are designated thus by others. This term is the pivot of the representation and categorisation of itinerant groups in Bengal, and it is comparable to the problematic term “gypsy”: both terms refer to various groups that are often perceived by outsiders as one community, even though these groups reject relationships with each other. Even with the help of etymological analysis, it is impossible to determine clearly for whom the term bede was first used, and what it originally meant. However, Middle Bengali sources indicate that the oldest variant of the term, bādiẏā, was primarily used to refer to snake catchers and charmers. 1 This meaning largely coincides with its common usage in West Bengal, but it contrasts with the prevailing usage in contemporary Bangladesh, where bede is often equated with “river gypsy.”

The categorisation of ‘Bedes’

According to the meaning of the English term, the so-called ‘River Gypsies’ of Bangladesh are characterised by living in groups and travelling around on boats [Figs. 2-3]. They earn their living through a wide variety of occupations: catching or charming snakes; performing acts with animals or as acrobats; selling remedies, household utensils, cosmetics, and jewellery [Fig. 1]; or treating rheumatism and toothache. However, these groups have their own names, often in accordance with their occupations (e.g., lāuẏā, māl, sāndār, sāpuṙe), vehemently reject the designation ‘Bede’ for themselves, and generally do not maintain any kinship relations with other ‘Bede’ groups. Rather, they are different endogamous groups that are perceived as one community only because of their ‘exotic’ commonality: moving around on boats.

Fig. 2: A fleet of ‘Bede’ boats in Bangladesh.

Fig. 3: A ‘Bede’ boat from inside.

The idea that different occupational groups supposedly form the ‘Bede’ community was already noted in publications by British colonial officials. 2 Influenced by the idea that the ‘Gypsies’ of Europe originated in India, these colonial officials often drew comparisons with local populations who held similar socio-economic roles, subsumed them under one term, and constructed them as one community. To this day, however, local and foreign scholars cannot agree on what kind of community the ‘Bedes’ are supposed to form, which is already evident from the contradictory terms used to categorise them: caste, community, class, ethnic group, race, and tribe. In West Bengal, the ‘Bedes’ are officially listed as a Scheduled Tribe, although they were officially a Scheduled Caste until 1976. In Bangladesh, meanwhile, they have not yet been officially classified at all. There are several reasons for this contradiction, the most important of which is the uncritical adoption of the colonial categorisation of the local population in independent India.

However, during British colonial times, also Bengali scholars contributed to this classification and, above all, to negative stereotypes of the ‘Bedes.’ For instance, in his article “On the Gypsies of Bengal,” Rajendralal Mitra (1822–1891) wrote: “In lying, thieving, and knavery he is not a whit inferior to his brother of Europe, and he practises everything that enables him to pass an easy idle life, without submitting to any law of civilised government, or the amenities of social life.” 3

This kind of harsh judgement is no longer voiced either by foreign or Bengali scholars. Yet, old and recent ‘exotic’ depictions of ‘Bedes’ in literary works by Bengali authors have been contributing their share of negative stereotypes on the ‘Bedes’ until today. Moreover, these portrayals suggest that the categorisation of different itinerant groups as one community was actually not invented by British colonial officials, but merely consolidated by them.

The portrayals of ‘Bedes’ in literary works

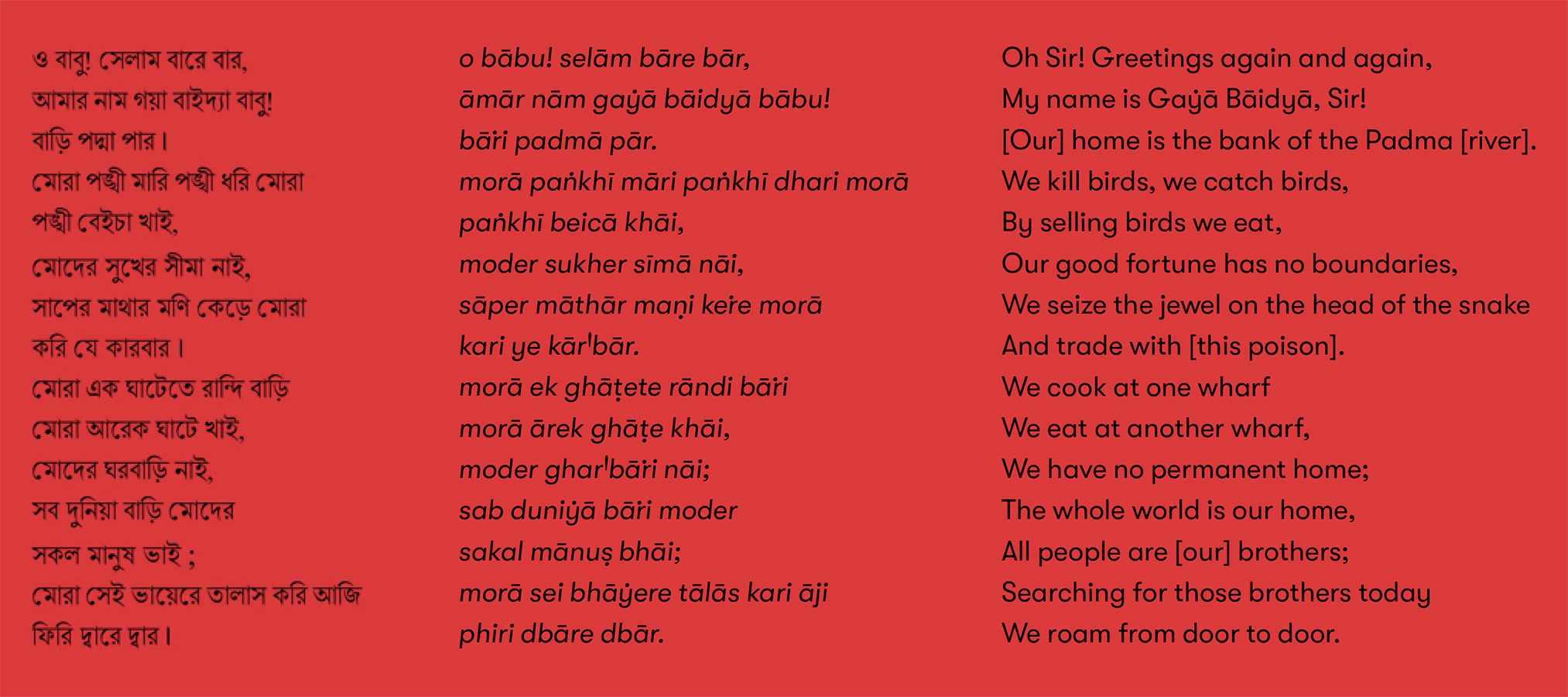

So-called ‘Bedes’ are often at the centre of novels, short stories, plays, and poems by well-known Bengali authors, including Tarashankar Bandyopadhyay, Kazi Nazrul Islam, Al Mahmud, Balaichand Mukhopadhyay (Banaphul), Shamsur Rahman, and Jasim Uddin. Similar to the portrayal of non-sedentary groups and individuals in European literature, their mobile lifestyle is often depicted in a highly romantic manner full of freedom, as in the introductory song of a ‘Bede’ in Jasim Uddin’s (1903–1976) theatre play Beder Meẏe (“The Daughter of a/the Bede”, 1951) [Box 1]. 4 . Beder meẏe. 5th ed. Ḍhākā: Palāś Prakāśanī, p. 12. This and all other extracts from Bengali literary works were translated from the Bengali original by the author of this article.] Moreover, also in these Bengali literary works the stereotyping of the itinerant woman is particularly striking: she is the focus of almost all works, consciously or unconsciously turning men’s heads, and is accordingly portrayed as a femme fatale.

Box 1: Introductory song of a ‘Bede’ in Jasim Uddin’s (1903–1976) theatre play Beder Meẏe (“The Daughter of a/the Bede,” 1951).

This is, for instance, the case for Radhika, the female protagonist in the 1943 short story Bedenī (“The Bede Woman”) by Tarashankar (1898–1971): “As if there is intoxicating power spread on every part of the slender, slim, long-limbed body of the Bedenī like a black snake; in her thick, curly black hair, in the parting like a white thread in the middle of her hair, in her slightly curved nose, in her two wide half-shut, curved eyes with an intoxicating gaze, in her pointed chin – there is intoxicating power in her whole body. As if she has arisen after bathing in an ocean of wine, the intoxicating power drips down, flowing along her whole body. As the scent of the mahuya flower fills her breath with intoxicating power, so the black figure of the Bede woman is intoxicating to the eyes. Not only of Radhika, this is a generic characteristic of the appearance of all the girls of this Bede community.” 5

The disproportionately frequent depiction of the non-sedentary woman compared to her male counterpart reflects the actual important role of ‘Bede’ women in income generation, during which they often have to deal confidently with male customers. The description of the ‘Bede’ women Rabindranath Tagore (1861–1941) watched from his houseboat in Shahjadpur (in present-day Bangladesh) in 1891 sheds light on the impression ‘Bede’ women might have left and still leave on these male outsiders: “The girls, too, look good – willowy slim and tall, compact, an unrestrained style of the body much like English girls. That means a quite open demeanour; they have an easy, simple, and fast mode in their movements – they do seem to me exactly like black daughters of the English.” 6

In Tagore’s case, it is the posture of the body and movements of the ‘Bede’ women that seem to be most impressive, apart from their slim and tall appearance. In another passage, he further describes how a ‘Bede’ woman aggressively argues with a policeman. ‘Bede’ women are physically active because of their occupations, which often require them to walk from village to village and on the streets of cities [Fig. 4]. Most importantly, they often come into contact with unknown men, and do so with self-confidence. Considering all of this, they indeed must have left an impression on men in particular, who would have been fascinated by their athletic figures and seemingly bold attitudes, in contrast to the general genteel womenfolk in Bengal of that time, especially among the urban higher strata from which the authors overwhelmingly originate.

Fig. 4: A ‘Bede’ girl with snakes on

her head in search of customers

on the streets of Dhaka.

Consequently, it is not surprising that sedentary men such as the authors of literary works were fascinated and inspired by these ‘other’ women. However, besides erotically charged portraits of ‘Bede’ women and the romanticisation of a non-sedentary life full of freedom, the reader is often also confronted with the hard everyday life of the ‘Bedes.’ The portrayal of the life of the ‘Bedes’ on the margins of society corresponds to the reality of many so-called ‘Bede’ groups. The socio-economic status of many such groups is comparable to that of so-called ‘untouchables,’ today often referred to as Dalits, which is why they have increasingly attracted the attention of development organisations since the 1990s.

The ‘Bedes’ as a target group of development organisations

Parallel to studies by scholars, 7 reports by development organisations 8 . Dhaka: Grambangla Unnayan Committee, p. 2] also uncritically cite sources from the colonial period and even push the idea that the various ‘Bede’ groups form one community – e.g., by referring to them as an ethnic group and speculating about their potential origin outside of Bengal. Whether this happens intentionally cannot be answered definitively. However, an ethnic minority in a country like Bangladesh – where some 98 percent of the population are Bengalis and around one-fourth live below the poverty line – is a more attractive target group for international donors than a ‘merely’ socially marginalised group of Bengalis. Furthermore, it also fits international narratives of endangered ethnic groups. An exoticisation and ethnicisation of the ‘Bedes,’ and the associated supposed threat of imminent cultural loss, have therefore dominated media coverage of the ‘Bedes’ in Bangladesh in recent years. This trend is in stark contrast to the efforts of the various non-sedentary groups themselves, who self-identify not only as Bengalis but also as Muslims.

The socio-cultural adaptation of ‘Bedes’

Contrary to the impression given by development agencies and the media that the ‘Bedes’ fear losing their supposedly ‘other’ culture centred on a by outsiders romanticised free life on the boat, my interviews with ‘Bedes’ revealed that they do not perceive their lifestyle as another culture. On the contrary, they are aware that their socio-economic role as itinerant traders and service providers is on a steady decline. For this reason, more and more ‘Bede’ groups are becoming permanently sedentary. The main reason lies in the fact that by the end of the 19th century the demand for their products and services was already decreasing, partly due to the expansion of infrastructure and new forms of entertainment. Accordingly, they often face harsh poverty today, and some even beg on the streets, including those of Dhaka [Fig. 5]. After settling down, ‘Bedes’ take up other occupations and also try to adapt socio-culturally to the majority population. This concerns, for example, the role of women: while non-sedentary ‘Bede’ women play an active role in income generation and also offer services and/or goods to men, ‘Bede’ groups that have become permanently sedentary increasingly practice gender segregation and forbid their women from working outside the home. This strategy of socio-cultural adaptation goes hand in hand with narratives of origin in which ‘Bede’ groups claim an Arab ancestry to secure social recognition within Bangladesh’s Muslim majority society.

Fig. 5: ‘Bede’ women begging

on the streets of Dhaka.

Interestingly, one essential element of these narratives of origin is the supposed relationship between the terms bede and “Bedouin,” established through folk etymology. 9 On the one hand, this establishes a credible connection to the Arab Bedouins for many people in Bangladesh, but on the other hand, it forces so-called ‘Bedes’ to accept the designation “Bede” for themselves, which they previously rejected vehemently. The ‘Bedes’ who proudly explained this erroneous folk etymology to me still continue to reject that designation. This obvious contradiction illustrates that many ‘Bede’ groups have recently been struggling with their identity, their place in Bangladesh’s society, and a consistent self-representation. Thus, the ‘Bedes’ are another example of contemporary Bangladesh being in search of its identity between Bengaliness and Islam: although the ‘Bedes’ I interviewed emphasise their Bengali identity, at the same time they are motivated to seek an origin in Arabia to achieve a better status within the majority society. 10

Outlook

Though the socio-economic status of so-called ‘Bedes’ in West Bengal is hardly any better than that of their counterparts in Bangladesh, they are less likely to face identity conflicts in a state that is much more heterogeneous both ethnically and religiously. Status as a member of one of the numerous Scheduled Castes and Tribes in India mainly promises direct socio-economic advantages, which is why some ‘Bedes’ in West Bengal have no problem with registering as members of a Scheduled Tribe. At the same time, the further reinforcement of the category “Bede” – i.e., the ethnicisation of the ‘Bedes’ in Bangladesh – automatically means socio-cultural marginalisation. This might attract more funds from development actors in the short term, but as a non-Bengali ethnic group in Bangladesh, the land of the Bengalis, the ‘Bedes’ would be second-class citizens in the longer run. The above-mentioned adaptation strategies adopted by various ‘Bede’ groups make it clear that this is precisely what they want to prevent. It therefore remains to be seen how national and transnational institutions will respond – that is, whether they will continue categorising the various non-sedentary groups, which in many cases are already sedentary, as one community, or whether they will allow these groups to become part of the majority society.

Carmen Brandt is professor for South Asian Studies at the University of Bonn, Germany. She received her doctorate for a dissertation on the representation of ‘Bedes’ in fictional and non-fictional sources. In her current research project, she investigates the socio-political dimensions of script in South Asia. Email: cbrandt@uni-bonn.de