Best Kept Secret, Jomon Heritage of Contemporary Japan

The current heritage of Japan has been changed by a number of factors, one of the most important being the transfer of focus from the emperor to the people. After World War II, Japan underwent several re-evaluations or interruptions caused by the occupying power (i.e., the United States), one of which was the reassessment of its sense of belonging and identity via the use of archaeological heritage.

The invention of new heritage took place, 1 and we can see an interruption to previous heritage narratives. These narratives had been linked to the legacy of the Meiji period and the emperor – partly related to the embodiment of the state – and to the Kofun period (AD 250-710), which reflected the creation of statehood with keyhole-shaped tombs that dominated the landscape.

As Kaner has suggested, “Direct links are often drawn between archaeology/Jomon peoples and the images of traditional life that are actively propounded by a government ideology of furusato: stimulating feelings for one’s native place in an increasingly displaced, rootless society. These images render the discoveries of archaeology comprehensible to the public who are encouraged to view the people of the past as their ancestors: there is a direct connection between contemporary ‘salary man’ and his stone-age forebear.” 2 This is well illustrated by the song “Furusato” (“old home” or “hometown”) with its strong emotional and nostalgic links to the countryside. Despite it being a children’s song created in 1914, it took on a new status as a national song performed during the closing ceremony of the 1998 Winter Olympics in Nagano.

Where the mountains are green, my old country home,

Where the waters are clear, my old country home.

Back in the mountains I knew as a child

Fish filled the rivers and rabbits ran wild

Memories, I carry these wherever I may roam

I hear it calling me, my country home

Mother and Fathers, how I miss you now

How are my friends I lost touch with somehow?

When the rain falls or the wind blows I feel so alone

I hear it calling me, my country home

I've got this dream and it keeps me away

When it comes true I'm going back there someday

Crystal waters, mighty mountains blue as emerald stone

I hear it calling me, my country home. 3

The countryside is where people and their ancestors are. Inventing tradition is meant to anchor the nation to the archaeological landscape, which serves as “witness”/testimony of belonging to this land and its ancestors: it is a landscape of the common countryside that belongs to all. The Jomon period is signified by museums often located on the outskirts of towns or in the countryside; they do not differ from other buildings.

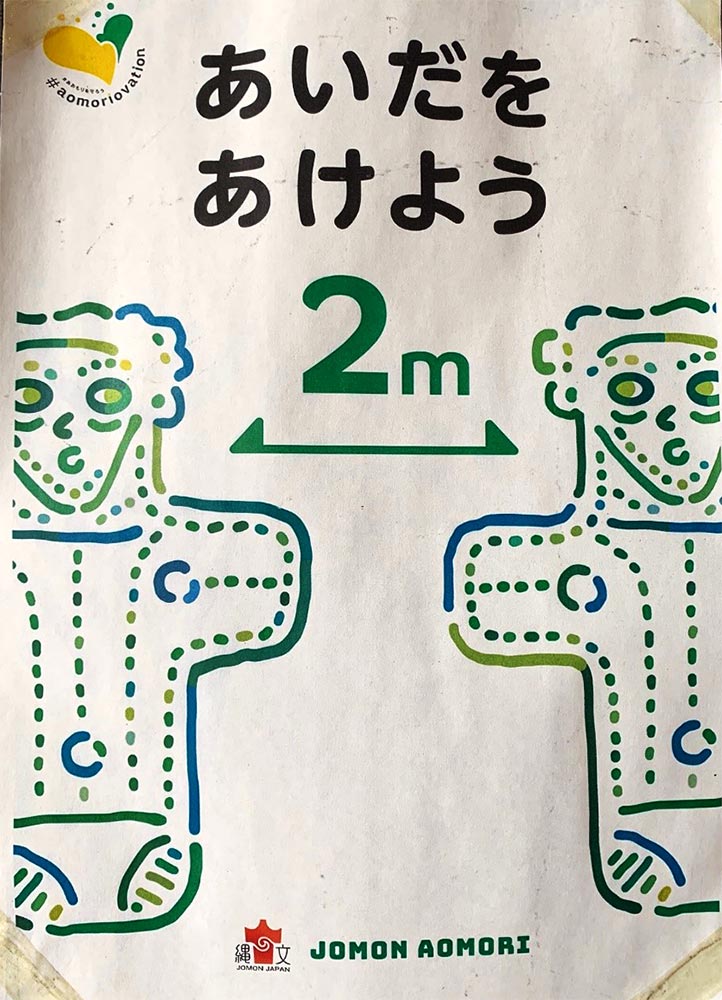

Fig. 1: Use of Jomon figurine from Sannai Maruyama by a local bar to convey COVID-19 restrictions to the customers, Aomori, Japan (Photo by Simon Kaner).

The Jomon period spans from c. 14,000-300 BCE. The prehistoric inhabitants of the Japanese archipelago made a wide range of material objects, remarkable for fisher-hunter-gatherers. Their ceramic creations, which include figurines as well as pottery vessels for food preparation and consumption, are of particular interest given their sophistication and variety.

For many, this summer is the first year since 2019 that travel to Japan has been possible, and my visit coincided with the period of the August obon holiday, when many families got together after three long years of the pandemic. In July 2021, 17 Jomon sites, including stone circles located in the north of Japan, were inscribed on the list of the UNESCO World Heritage Sites. As a heritage professional and archaeologist, I decided to visit them. As in previous years when I followed the Shinano River Jomon Heritage Trail, the Jomon sites were somewhat hidden for the foraging tourist. In contrast to the well-known historical sites in Kyoto, Tokyo, or Nara – where the English-based leaflets and brochures inform tourists of the historical, cultural, and often artistic importance of those locations – the Jomon sites are Japan-focused.

This is not, I suggest, due to any lack of contribution of worldwide impact by Jomon peoples, such as technologies still used today. For example, we know that the first examples of lacquer use are from Jomon sites, and the first containers made of clay were created by the inhabitants of the area around the Sea of Japan / East Sea, also including China and the Russian Far East. Jomon cuisine, rituals, and continuity of occupation of particular locations have no equivalent among historical or contemporary foraging communities.

Jomon belongs to the Japanese people. Their material culture and associated archaeological narrative is now part of a grassroots heritage consciousness. The creativity of curators, educators, artists, and musicians who take part in the modern Jomon festivals across this region is inspired, and Jomon images are also part of the most popular genre of literature, manga. As foreigners, though, we do not easily see or hear it: Jomon remains one of Japan’s the best kept secrets.

Liliana Janik, Deputy Director of the Cambridge Heritage Research Centre, University of Cambridge. Email: lj102@cam.ac.uk