A besieged artist: Hal Wichers in the Netherlands Indies

Many artists from the West found their own little paradise in pre-War Netherlands Indies, and played a significant role in the local and international art world. However, the Japanese changed all that when they invaded in 1942; European artists and their artistic products and thinking did not fit in the occupier’s anticolonial frame of mind, or indeed in the immediate aftermath of WW II. So what happened to the artists who got caught between the cogwheels of the war and Bersiap period that followed? And what happened to their art work? This article presents one case of art looting.

Hendrik Arend Ludolf Wichers was born in 1893 at Tarutung on Lake Toba on Sumatra, where his father (from Groningen in the north of the Netherlands) was in garrison, and eventually promoted to Lieutenant Colonel of the Royal Netherlands Indies Army. In the early years of the 20th century the family returned to the Netherlands, where the young Wichers graduated from the National Academy of Fine Arts in Amsterdam, followed by a study in tropical agriculture. He sailed back to the Indies in 1919 and worked first at a tea estate, then at a cinchona plantation, but in the end he chose to become a full time painter on Java. Wichers did indeed show considerable talent in the many impressionist portraits and landscapes that he made, not to mention volcanos, paddy fields, townscapes, flame trees or Balinese temples; he had many exhibitions and his works sold well. Among his friends were other artists of renown, like Carel Dake, Ernest Dezentjé and Leo Eland, all of whom were members of the prestigious Art Association of Batavia, established in 1902.

Wichers was soon able to commission the build of a large villa, ‘Eagle’s Nest’ (Arendsnest), which had a spacious studio; the house stood in what was Berg en Dal, now Ciumbuleuit, in the North of Bandung. A grand driveway led to a generous garden with purple bougainvillea and red hibiscus that embraced a big pond and a rock garden; the gardens also boasted fruit trees and a kitchen garden, and there was even a private bomb shelter, just in case. From the terraces of the house there was a terrific view of the lush Bandung landscape, which ended at the foot of the Tangkuban Perahu volcano, and old photos show Wichers in comfortable tropical gear working in the garden or in his studio adorned with paintings.

During the Japanese occupation, Wichers and his eldest son were put into the Cimahi camp for men. His wife, Nicolette Henriëtte Bleckmann (related to the famous Willem Bleckmann (1853-1942), the painter who first introduced impressionism to the Indies) used her German maiden name to steer clear of internment. Nicolette and the younger children managed to continue living in their own house, but had no income and their bank accounts were frozen by the Japanese. They relied on the sales of personal items, such as clothing and crockery, just to feed themselves. Japanese soldiers would frequently visit unannounced upon hearing Nicolette’s piano playing; they were also enamoured by her children. In the house, she had also stowed away - at considerable risk to her own life - two other little ones, Peter and Truitje, grandchildren of Charles Welter, the former Secretary of Colonies. Their mother, acting in fear, took them back in due course, and the three of them ended up in a civilian camp. In addition to the children, two men - Wil Kaptein and Walter Walraven - managed to remain hidden in the house throughout the war and came out alive. Hiding from the Japanese enemy was very difficult for people who, like the Dutch, were so conspicuous in terms of skin colour and size. It was also very dangerous, as those who were discovered and captured were commonly beheaded on the spot.

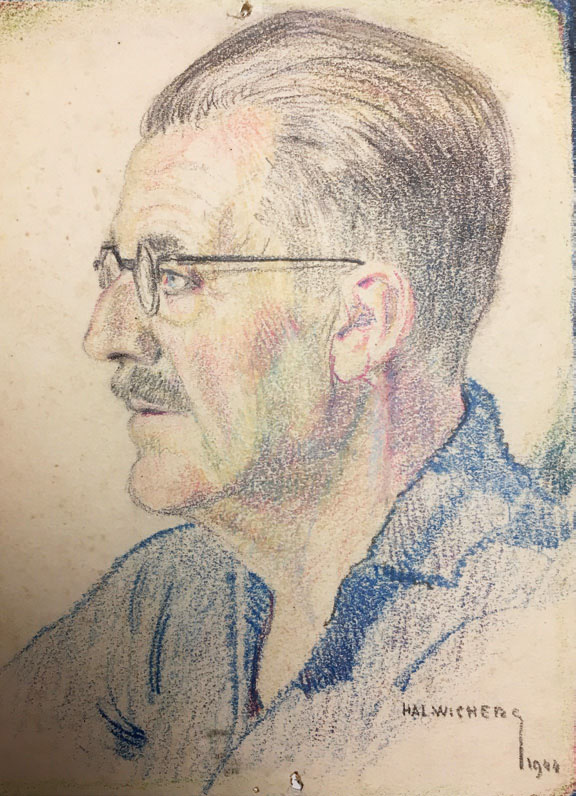

In the civilian camp Wichers had a few bits of chalk and some pencils, and would be compelled to draw portraits of the hated Korean guards; he also captured the images of his fellow prisoners, and gave them the drawings for free. Both Wichers and his son survived internment and were reunited with their family. After the end of the war, and Japanese surrender, their worst fears came to pass: Indonesian thugs came from their villages to the villas up on the hills to attack and plunder the Europeans and anyone who looked European; bodies were thrown into the Cikapundung River nearby. As their house was very isolated, the Wichers’ situation became extremely precarious and they were forced to flee, leaving everything behind - all their possessions, including the large collection of paintings. Initially they were given shelter by friends, the Neervoort family, but the local thugs came there as well and shot the oldest daughter Nicolette through the door that she was attempting to barricade. There was little choice but to flee the country, and the unhappy family embarked for the Netherlands on the passenger ship SS Johan de Witt. Back in Europe they were taken in by the Bleckmanns in their house in Nijmegen.

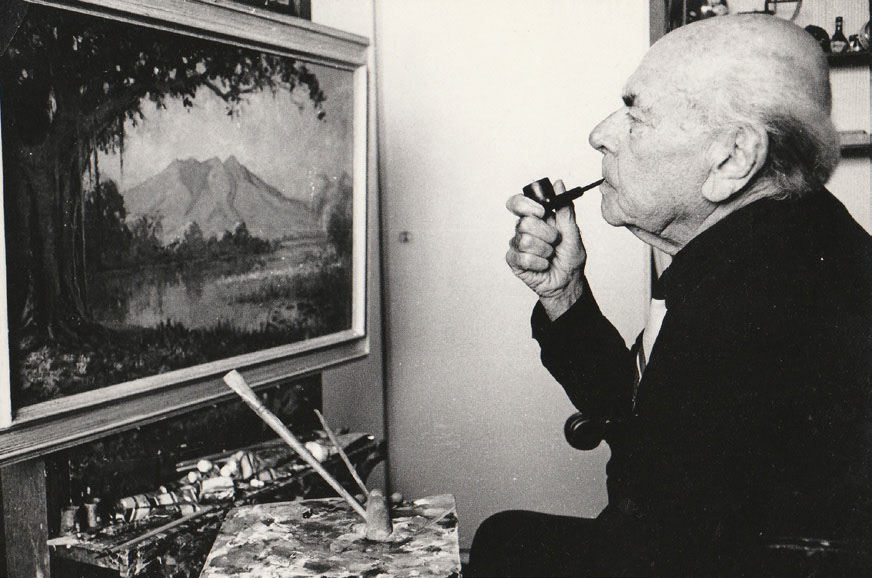

In Bandung, the Wichers house, including all its contents, had meanwhile been confiscated by the Indonesians. Not a single rupiah was paid for the house or for the many (unregistered) objects and paintings stored in the house. There is not a trace left of these items. In fact, after closer inspection it appears that even the house itself has disappeared! Now in post-war Netherlands, Wichers remained silent about their dramatic years in Indonesia, but he did continue to paint and exhibit his ‘beautiful Indies’ and the familiar themes from a past gone forever.

With thanks to Mrs. Tjieke Deuss-Wichers, daughter of H.A.L. Wichers, and Dr Leo Ewals.

Art-historian Louis Zweers (PhD) was a former lecturer at the Department of History, Culture and Communication of the Erasmus University Rotterdam. He works now as an independent scholar and author. His current research focuses on the disappearance and looting of art heritage objects in the former Dutch East Indies/Indonesia 1942-1957. His findings will be published in a book by Boom Publishers, Amsterdam in 2019.