Bernard Fall: A Soldier of War in Europe, A Scholar of War in Asia

Over the last fifty years, a lack of analysis on Bernard B. Fall (1926-1967) and his scholarship has been a significant gap in the historiography on the First Indochina War (1946-1954) and the Second Indochina War (1955-1975). Since the Vietnam War ended, the failure to recognize how military force cannot compensate for the lack of a politically attainable goal remains prevalent. As Fall once remarked, “A U.S. Marine can fly a helicopter better than anyone else, but he cannot give a Vietnamese farmer an ideology to believe in.” In much the same way, a Russian pilot will not be able to convince Ukrainians that political reconciliation is possible. Rather, Russia’s unprovoked invasion has made its political legitimacy impossible to maintain with every passing day that Russia continues to destroy the Ukrainian people and their country.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine in early 2022 evokes a failure to learn the many lessons Bernard Fall sought to convey in critiquing American operations in Vietnam in the 1960s and as France sought to control Indochina in the 1950s. Among his contributions was Fall’s demand that policy-makers recognize the primacy of political legitimacy over military force. He noted this tendency to over-rely on military power in 1962, writing: “To win the military battle but lose the political war could become the U.S. fate in Vietnam.” He believed that no invading force could possess sufficient military power to compensate for its political standing if that force lacked political legitimacy among the society it sought to control.

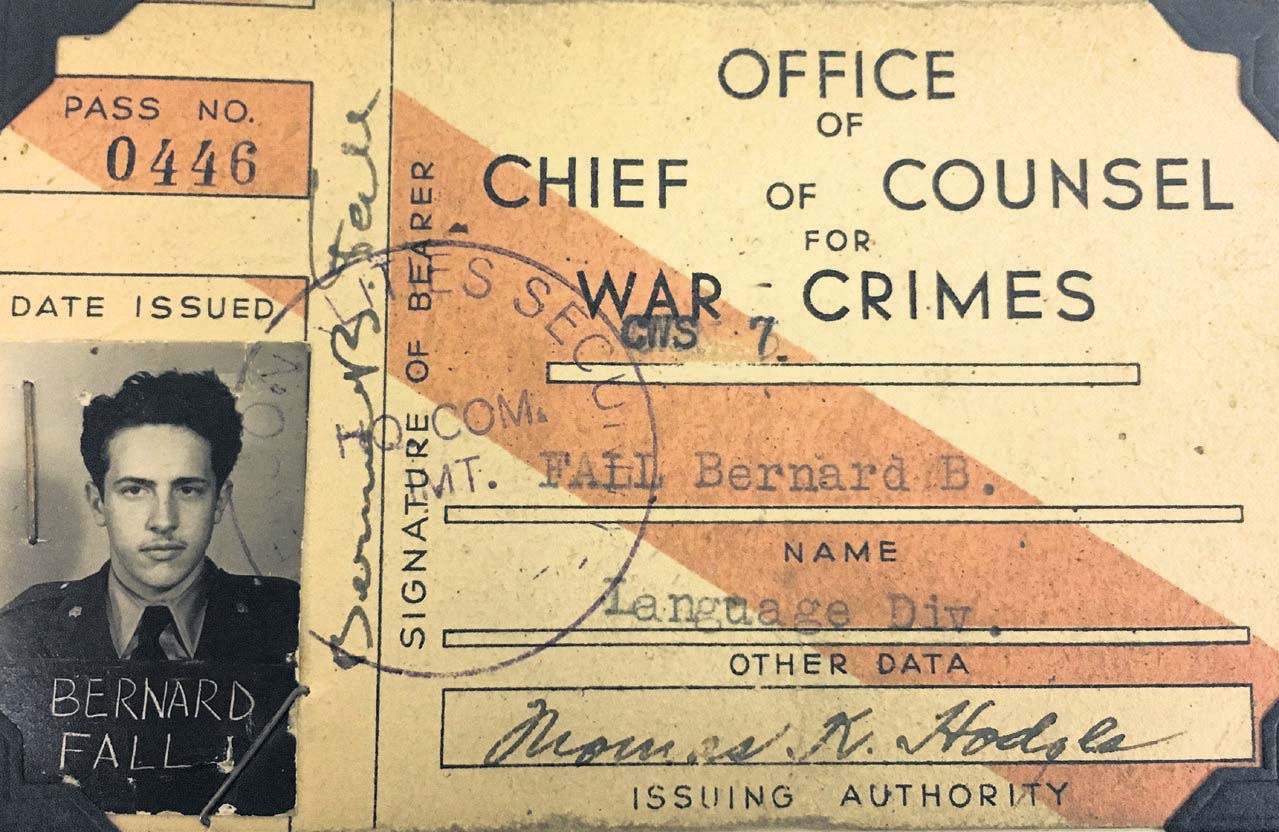

Born in Vienna in 1926, Bernard Fall was a Jew whose family emigrated to France after the Anschluss of Austria in 1938. When he was 16, Nazi forces murdered his parents in Vichy-held France, at which point he joined the French Resistance in 1942, Forces Françaises De L’Intérieur (FFI) in 1943, and the French army in early 1945. After WWII, he became a research analyst for the War Crimes Commission during the Nuremberg Trials. In 1952, he moved to the United States as one of the first scholars in the new Fulbright International Study Program. In 1953, Fall traveled to Indochina to conduct research on the Viet Minh for his Ph.D., which he completed at Syracuse University in 1955. At that point, he quickly became one of the foremost scholars on warfare in Southeast Asia after World War II. He is most well-known for his books Street Without Joy: Insurgency in Indochina (1961) and Hell in A Very Small Place: The Siege of Dien Bien Phu (1966). 1

Fig. 1: Office of Chief of Counsel for War Crimes ID Card.

An Early Scholar of War in Indochina

Among the many factors that distinguished Fall from other contemporaries was his first-hand analysis of France’s war in Indochina (1945-1954) and his analysis of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam’s (DRV) formation and administration of northern Vietnam after September 2, 1945. His first book, The Viet-Minh Regime, was the first analytical study of the DRV written in English when it was published in 1954. 2 In the years after 1955, Fall continued to evolve and develop as an analyst of political warfare. He eventually became a leading scholar among journalists and other intellectuals assessing U.S. policy during the early stages of the Second Indochina War in Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos.

After 1963, individuals in the West who read the translated works of The Collected Writings of Ho Chi Minh, Vo Nguyen Giap’s People’s War, People’s Army, and Truong Chinh’s Primer for Revolt did so through the lens Fall provided them as editor of these collections. 3 Finally, as opposition to American involvement in Vietnam intensified after 1965, American students and international readers learned more about Vietnam and U.S. policy in Southeast Asia through a book Fall co-edited called The Viet-Nam Reader: Articles and Documents on American Foreign Policy and the Viet-Nam Crisis. Fall, along with co-editor Marcus Raskin, collected and published this book in early 1965. The Viet-Nam Reader was a notably non-partisan collection, and it provided readers with a balanced range of political views as the early anti-Vietnam War movement began to emerge in the United States. 4

Fig. 2: Fall in Indochina, 1953.

Among academics writing about the Vietnam War today, it has become obligatory to include at least one bibliographic reference to Fall’s books. However, this simple but respectful acknowledgment underestimates the importance of his scholarship. To be sure, Fall’s work is difficult to categorize because of the interdisciplinary approach to Vietnamese studies he developed. Yet, this quality also indicates that he offered a new approach to writing about warfare after World War II. For example, Fall adopted an area studies approach to Asia when this field was only emerging. He also wrote about international relations with a directness found in political science but infused his analysis with historical context and cultural analysis of Vietnamese society. Finally, as a recognized expert in his day, he was adept at incorporating colourful anecdotes that enlivened his thoughts on policy, guerrilla warfare, and global politics.

Fall’s analysis of Vietnamese revolutionary warfare also had a pragmatic element. He incorporated his extensive knowledge of military tactics, techniques, and procedures – gathered from his time-fighting in the French Resistance and French army during World War II – in almost all of his writing. His ability to write for the average reader was another notable characteristic. He wrote dozens of articles for numerous journals that included The New Republic, The Nation, Current History, and popular outlets ranging from the Saturday Evening Post, The New York Times, and others. As a result, and as a public intellectual, he was recognized by U.S. personnel and other journalists as a scholar who knew France’s war against the Viet Minh first-hand. Understandably, this provided significant legitimacy to his critiques of American policy when it escalated its operations in Vietnam.

Fall’s Relevance Today

In 2022 and in the future, readers will benefit from learning more about Fall's influence and how his scholarship may increase our understanding of political warfare. Even a quick study of his writing reveals its relevance to war in Ukraine, Afghanistan, or elsewhere. As indicated earlier, he emphasized how administrative control over local populations mattered far more than military power. This administrative focus – which the Viet Minh and National Liberation Front forces prioritized in their Maoist-inspired revolutionary warfare – gave them an edge over stronger military forces arrayed against them. As Fall put it, “When a country is being subverted in an insurgency, it is not being out-fought. It is being ‘out-administered.’” 5 His scholarship, thus, provides instruction for those seeking to understand how comparatively weak forces can undermine stronger military forces.

Fig. 3: Bernard Fall and Vietnamese Prime Minister Pham Van Dong, 1962

In another historical case during Fall’s career, he reflected on how a brutal, illegal, and unprovoked land invasion of one country of another created a chain of events leading to other wars. The invasion referenced here was the Korean War which resulted from vast miscalculations. In an echo resonating today, the North Korean invasion of its neighbour directly resulted in renewed German military rearmament as Chinese and Russian threats to the global security order increased. In a compromise to permit, if not support, German rearmament in 1951, France demanded that the United States guarantee its position in its colonies in Indochina. In exchange, France would remain committed to collective defense through a proposed European Defence Community united against Russian and Chinese encroachments. Fall began to recognize how, in 1951, the security guarantees the United States provided France began to pull the United States further into the failing French reoccupation of Indochina. Thus, as one war began, it primed the furnaces for another.

Ultimately, readers who are new to his work will find much on insurgency and revolutionary warfare that is critically relevant to the conduct of warfare today. Among those looking for an evolution in military history, Bernard Fall’s writing is valuable because he wrote about the political and social dimensions of warfare as it functioned within a Vietnamese society enduring the broader Cold War. Tragically, Fall died in February 1967 when he tripped a landmine while on patrol with U.S. Marines in Thua Thien Province, near the Vietnamese city of Hue. He was 40 years old. However, for readers who seek to understand how supposedly “weaker” forces confronted and defeated more powerful military forces – similar to the current war in Ukraine and other conflicts – few authors explained this phenomenon in the 20th century as comprehensively as Bernard Fall.

Nathaniel L. Moir, Ph.D., is a research associate in the Applied History Project at the John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University. He is the author of Number One Realist – Bernard Fall and Vietnamese Revolutionary Warfare, published by Hurst (London) and Oxford University Press (New York). E-mail: nmoir@hks.harvard.edu

All photos are courtesy of the Bernard Fall family and used by permission.