Austronesians and “Localism” in Taiwan, Hawaiʻi, and Aotearoa New Zealand

In her keynote address at the New Zealand Asian Studies Conference held in November 2023 at Te Whare Wānanga o Waitaha – The University of Canterbury in Ōtautahi (Christchurch) in Te Wai Pounamu, the South Island of Aotearoa New Zealand – Professor Bavaragh Dagalomai/Jolan Hsieh (謝若蘭 Xiè Ruòlán) of the Department of Ethnic Relations and Cultures at National Dong Hwa University in Hualien, began by speaking in Siraya, her ancestral language.

The Siraya people and Taiwan’s indigenous Austronesian history

The act of speaking their ancestral language is a powerful gesture of cultural reclamation by members of the Siraya community, the indigenous inhabitants of the area around Tainan, the part of Taiwan where a colonial outpost was established by the Dutch in the early 1620s, setting in motion the processes which would see Taiwan become a place where the indigenous population have become a subordinated minority. The Siraya were among the first of Taiwan’s Austronesian peoples to experience this process of subordination, as their traditional lands were located in the places where incoming peoples were concentrated from the mid-17th century onwards. 1 Until a few decades ago Siraya was primarily a language preserved in old texts, the first of which were produced by Dutch missionaries with the goal of Christianising the Siraya population, with Siraya people in the 20th and 21st centuries having become primarily speakers of various forms of Chinese. 2

Siraya, like the other indigenous languages of Taiwan, belongs to the Austronesian language family, a family which spread out from Taiwan into Southeast Asia and then through the Pacific Islands and also across the Indian Ocean to Madagascar. Aotearoa New Zealand and Hawaiʻi are the southernmost and northernmost sites to which Austronesian languages spread in the era of settlement by people using traditional Oceanic seafaring techniques. 3

The present-day situation of the Siraya people, like that other Austronesian-background peoples in Taiwan, is similar to that of Māori people in Aotearoa New Zealand, and Kānaka Maoli/ʻŌiwi – Native Hawaiians – in Hawaiʻi. They are minorities in places dominated by populations that have moved there in the course of the last few centuries. Loss of land, of political self-determination, and of language and culture have been the common historical experiences of Austronesian-background peoples in all three places. Such processes necessitate ongoing action for the assertion of political and cultural rights and for the recovery of languages that have lost ground to those spoken by the incoming populations. 4

The identity politics of non-Indigenous majorities in Taiwan

While the political and cultural subordination of indigenous peoples to populations which arrived later is something found across the world, from Siberia, to mainland and island Southeast Asia, to Northeast Asia to the Americas and the Caribbean and to Australia, there is a distinctive set of features that mark the situations in Taiwan, Hawaiʻi, and Aotearoa New Zealand as historically linked. 5 We can argue that the three places have been shaped by a common set of historical processes that involve interactions between Austronesian peoples, the Chinese and wider East Asian realm, the Americas, and the Anglo-Celtic and Continental European cultures of the North Atlantic. These forces began to interact directly with each other in the 1500s. In all three cases, we see processes of demographic, cultural, linguistic, and political de-Austronesianisation. At the same time, in all three cases, we see the emergence of non-Austronesian local cultures and identities which assert their distinctivness and the importance of their own histories and identities that contrast both with those of the places from which their forebears originated and from those of societies with which they have much in common. In recent times, this assertion of cultural distinctiveness by the non-indigenous local majorities has entailed a complex combination of support for and resistance to the re-assertion of the cultural and political rights of the original Austronesian inhabitants. 6

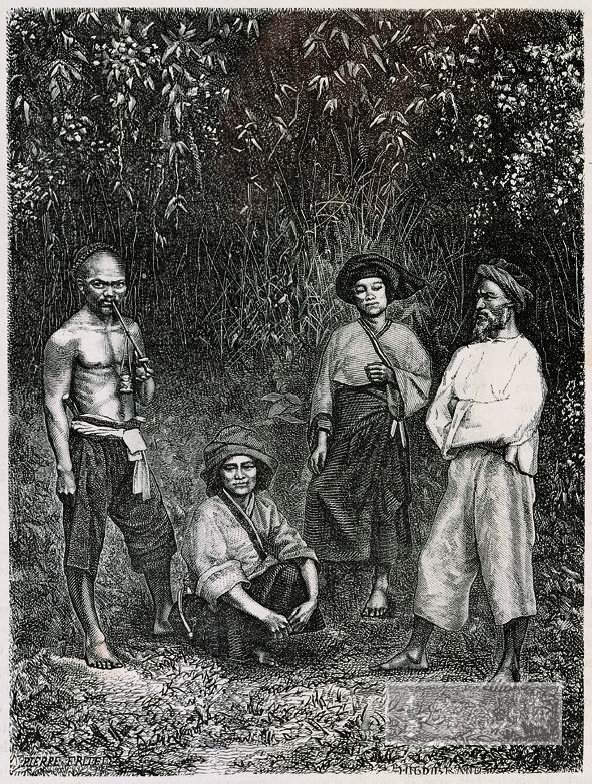

Fig. 2: A sketch of the Siraya people in southwestern Taiwan by P. Fritel (before 1895). (Image in the public domain available on Wikimedia Commons)

In Taiwan this assertion of the cultural distinctivenss of the local non-Austronesian population is primarily articulated in the form of a Taiwan localism that presents Taiwan culture and history as distinct from those of China, a localism that is strongly connected to the project of achieving Taiwan independence – the de jure recognition that Taiwan is a sovereign independent entity, not part of the territory of a Chinese nation-state. 7 Although the majority of Taiwan’s population is of Chinese descent, non-Austronesian cultural and political activists who are involved with the idea of articulating Taiwanese distinctiveness contest the idea that Taiwan’s culture and history are simply a subset of the history and culture of China. Although Taiwan’s Austronesian history is understood as part of what creates the distinctiveness of Taiwanese culture, the narratives which affirm that Taiwan’s history is separate from that of China tend to concentrate on aspects of the historical experience of Taiwan’s Han population in the years between the 1600s and the present which are not fully shared with the mainland. The 50 years between 1895 and 1945 when Taiwan was a colony of Japan are central to presenting Han Taiwanese history as being separate from that of the Chinese mainland. 8

Taiwan “localism” in comparative perspective

We cannot discuss questions associated with Taiwan’s historical and cultural relationship with the Chinese mainland in isolation from the strong assertion of the government of the People’s Republic of China that Taiwan is part of its territory and the political consequences which that claim has for Taiwan’s future. At the same time, the parallels between localist images of the distinctiveness of the Taiwan past and the images of local culture and history that are produced by non-indigenous majority populations in Hawaiʻi and Aotearoa New Zealand are striking. While the formal political circumstances of Hawaiʻi and Aotearoa New Zealand are very different – the latter being a sovereign and independent nation-state with its own government and armed forces, and the former being the 50th of the 50 states of the United States of America – in each case the local non-indigenous majorities have a strong sense of their own distinctiveness. This sense of distinctivenss is framed in part by distinguishing “true” locals from “non-locals”. “Non-locals” are non-indigenous inhabitants of those lands whom the old settler majority populations – the “true” locals – frequently depict as outsiders, a phenomenon that that is also found amongst “locals” inTaiwan.

A good part of the energy associated with Taiwanese localism involves the distinction made within Taiwan between those Han Taiwanese whose families were present on the island prior to 1945, people whose ancestral languages are Taiwan Hokkien and Taiwan Hakka, and people who arrived from the Chinese mainland after 1945 when Japanese rule ended and Taiwan was brought under the control of the goverrnment of the Republic of China. The most important part of this post-1945 population are those who came to Taiwan after the 1949 defeat of the government of Chiang Kai-shek, then president of the Republic of China, by the forces of the Chinese Communist Party in the Chinese Civil War.9 This emigré/refugee population was strongly linked to the ideology of Chinese unificatory nationalism which held that the peoples of Taiwan were part of a larger Chinese nation and that Taiwan and the Chinese mainland were a single entity, an ideology that was taught in Taiwan schools between the 1940s and the 1980s. Since the 1980s the rejection of this ideology has often gone hand in hand with an assertion that the pre-1945 Hokkien and Hakka-background Han peoples are, along with Taiwan Austronesians, those who are the true exemplars of Taiwan local culture. 10

In Hawaiʻi the sense of the distinctiveness of non-indigenous local identity is much less formal; it focuses on the culture of “Locals” – Hawaiʻi people of Asian-Pacific descent who are not native Hawaiians (although this is often an ambiguous issue because so many people in Hawaiʻi are of mixed descent) 11 – as opposed to the culture of Haoles – Caucasians, particularly those from the US mainland. 12 Pijin – Hawaiian Creole English – which emerged on the plantations where Asian migrants were working in the 19th century – is a powerful informal marker of the division between the culture of Locals and that of Haoles. 13 Pijin is full of Hawaiian words, along with words from Chinese languages and from Japanese, and functions as a badge of localness that is similar to the way in which Taiwan Hokkien funtions as a badge of localness that contrasts with Mandarin – the main language of education and of public life in Taiwan, a status that is similar to that of Standard American English in Hawaiʻi.

Non-indigenous local distinctiveness in Aotearoa New Zealand is primarly manifested in the concept of Pākehā culture, the culture of New Zealand’s Anglo-Celtic majority. For intellectuals in particular, the articulation of a distinctive Anglophone New Zealand culture that is specific to that place and different from the culture of Britain, which was historically the source of the majority of New Zealandʻs non-indigenous inhabitants, has been an ongoing preoccupation. 14

A central plank of these cultural narratives is that of a bi-cultural nation, Māori and Pākehā (which has generally meant Caucasians of Anglo-Celtic heritage), with Māori culture being what differentiates New Zealand from other white-dominated English-speaking countries (e.g., the United Kingdom, Ireland, Australia, Canada, and the United States). In recent years there has been more and more focus on the ways in which this Pākehā-centred narrative of non-Māori New Zealand identity excludes the cultures of non-indigenous people living in Aotearoa New Zealand who are not Pākehā, with Chinese, Indian, and other Asian New Zealanders being one of the most important groups (Asian background people were 17.3% of the Aotearoa New Zealand population in 2023, a percentage only slightly smaller than that of the Māori population). 15 Indeed, there are grounds for arguing that one of the shaping forces in creating Pākehā identity in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was the construction of Asian and, in particular, Chinese cultural worlds as an “Other” against which a Māori and Pākehā New Zealand was to be defined. 16 Much of the work of people concerned with Chinese and other Asian cultures in Aotearoa New Zealand over the last decade or so has been to criticise this construction of New Zealand localism, simultaneously showing its historical inaccuracy and its effects in the present. 17

Dialogue and contention with Austronesian cultures

Taiwan and Aotearoa New Zealand thus represent cases of lands that have been de-Austronesianised in which the construction of a local identity by settler majorities has involved not only the attempt to differentiate local histories and identities from those of the homelands from which those settling majorities originated but also, in complex and different ways, an engagement with Austronesian cultures as ways to define their historical distinctiveness. At the same time, a rejection of China and Chinese culture has been an element in that articulation of local culture. This rejection of China and Chinese culture is much less prominent in the formation of naratives of Local identity and culture in Hawaiʻi, where the “Other” against whom Hawaiʻi’s “Locals” defined themselves was primarily the Haole – Caucasians, and in particular, those from the US mainland.

In the culture of these three non-Austronesian local cultures – those of the “Taiwanese” in Taiwan (defined against Chinese mainlanders), those of “Locals” in Hawaiʻi (defined against Haole mainlanders), and those of “Pākehā” in Aotearoa New Zealand (defined against other countries dominated by English-speaking whites, and – to a great extent – against Asian and especially against Chinese people who are living or seeking to live in New Zealand), narratives and images of localism and the authenticity associated with it have been formed from histories in which Austronesian, Chinese, and Anglo-European cultural forces have contested with each other. Whether the non-Austronesian cultures are primarily Sinophone (in the case of Taiwan) or primarily Anglophone (in the case of Aotearoa New Zealand) or Creolised (in the case of Hawaiʻi) has perhaps been less important than how each of them has sought to configure localism in dialogue and in contention with the Austronesian peoples whose lands they have come to occupy.

Lewis Mayo is a Lecturer in Asian Studies at the Asia Institute, The University of Melbourne. email: lmayo@unimelb.edu.au