An art historical parallax: the subject, spectacle, and myth of/in Juan Luna's "Parisian Life"

“[E]very age had its own gait, glance, and gesture.”

—Charles Baudelaire, The Painter of Modern Life 1

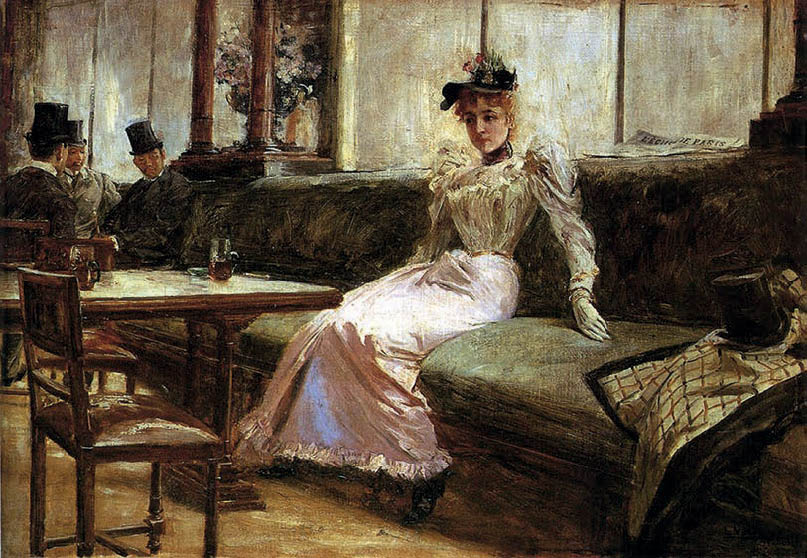

Parisian Life (1892), by Filipino artist Juan Luna, features an interior scene in a café with a woman seated prominently on a banquette and three men at the far left corner. It fetched $859,924 at Christie’s auction in Hong Kong in 2002, an exorbitant sum paid by the Government Service Insurance System (GSIS), the pension fund institution of the Philippines.

The painting is a richly layered portrayal of contemporary social norms, gender politics and national allegory. Formal and social analyses reveal a woman, believed to be a prostitute, as the subject of the male gaze. Women in Paris were increasingly seen as a threat to the status quo. If they did not conform to the traditional role of a femme honnête (respectable woman), they were seen as the courtisane, or the prostitute. As a dangerous woman, the prostitute bore the stigma of infecting men with venereal disease.

The unregistered prostitute, who constituted a growing labor force in Paris, was regarded as “the site of absolute degradation and dominance, the place where the body became at last an exchange value, a perfect and complete commodity”.1 In constant circulation like money, yet at times also clandestine, the prostitute could be considered as the spectacle in the flesh, which Manet’s Olympia (1863) embodied. Indeed, she represented desire and death, a femme fatale who was both loved and loathed.

Juan Luna, Parisian Life, 1892, oil on canvas, 20.94 x 29.72 in. (53.2 x 75.5 cm.). National Museum of the Philippines, Manila

Parisian Life mirrors the constructions of masculinity and civility among the three men wearing European clothes, “part of a larger attempt at nationalist self-fashioning”.2 Despite the civilized middle-class body, their brown faces disclose their racial identity. They are identified as the Filipino patriots Jose Rizal, Juan Luna (frontal pose), and Ariston Bautista (holding cane handle). They are fixed on the woman whose very appearance in a café is an erotic encounter itself. While Luna’s self-portrait exhibits fatigue or even ennui, Bautista registers the curiosity and pleasure of a voyeur “in a fairly lascivious way” tilting his head toward the sexually objectified cocotte who furtively acknowledges his gaze.3 Far from heroic, Juan Luna brought to light the hypocrisy and duplicity of his milieu and the general anxiety against the prostitute. Despite of and whether the black umbrella functions as a barricade or signifies the phallus, the conventional prostitute of Parisian Life still approximates the familiar Old World—patriarchal—whose double standards Luna and the ilustrados enjoyed.

While Luna’s body of work crystallized the artistic and economic negotiations he had to perform as a painter, his life and home became the model of the divided self and the imagined community. Contrary to nationalist historiography and its grand, developmental narrative, the growth of the new ‘Filipino’ consciousness was uneven, ambiguous, and problematic. Moreover, the yet-to-be-‘Filipino’ was already endangered. Although the prostitute personified the threat of sexual corruption, moral disintegration and physical death in Parisian Life, the latent fear of the ilustrados was caused, in general, by women and, figuratively, by France.

In sum, Juan Luna’s Parisian Life is an Impressionist rendition of an interior of a café inhabited by a cocotte, a dandy, and three ilustrados in Haussmannized Paris. It can be read as an ideological unveiling not only of late 19th-century French modernity, but the “gait, glance, and gesture” of the other spectacle and myth that it mirrors: the problematic and complex formation of the nation-state and the scarcity and fetishism of the Filipino. Indeed, meaning, to echo Jacques Derrida, is always “deferred”.

Pearlie Rose S. Baluyut teaches at SUNY Oneonta (PearlieRose.Baluyut@oneonta.edu).