Art and aesthetic environmental awakening at Plum Tree Creek

Socially engaged art practices, such as those found at the Plum Tree Creek project in Taiwan, allow artists, architects and the local community to collaborate in order to revive everyday-life customs, perceptions and representations that are attentive to the environment, whether natural, human, or built. The Plum Tree Creek project regenerated environmental aesthetics that both embodied and reflected the specificity of local culture, history and geography, at a time when the community came under threat of systematic urbanization. The Plum Tree Creek project offers an example of ‘new genre land art’, comparable to Joseph Beuys’ idea of ‘Social Sculpture’; this participatory project has indeed had a sustainable social impact by awakening the local community through environmental aesthetics.

Art as environment

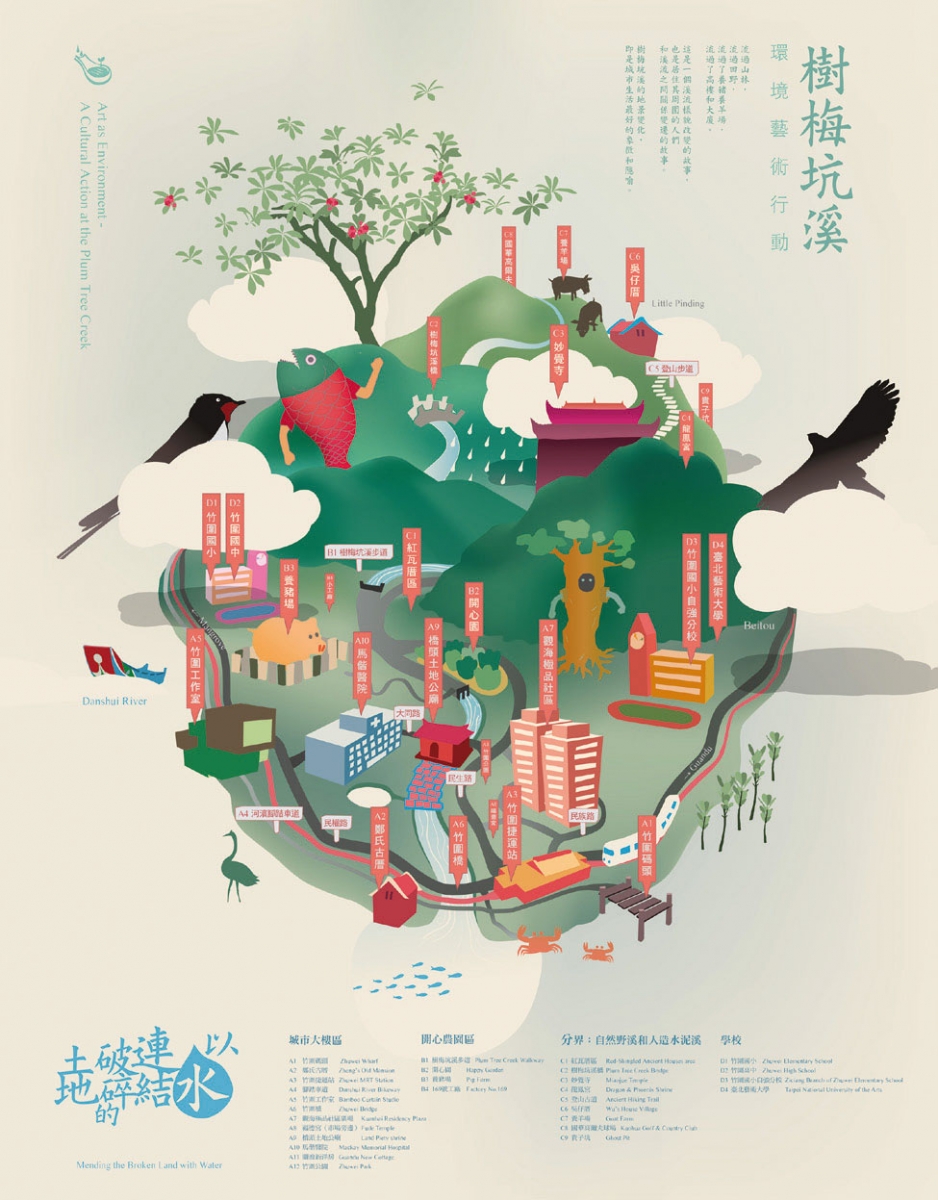

The project Art as Environment: A Cultural Action at Plum Tree Creek was initiated in 2010 by artists and architects based in the area of Zhuwei in New Taipei City. The project was curated by Wu Mali, an activist and practicing artist, whose work most often reflects socio-cultural issues, such as environmental protection, paternalism, and communities whose histories have been forgotten by mainstream narratives, for example, women factory workers and housewives. Wu Mali was inspired by American artist Susanne Lacy’s ideas of ‘new genre public art’, and community cultural interventions of the 1990s. Ideas of participatory art practices that incorporate conversations – what art theorist Grant Kester calls ‘conversation pieces’ – also became paramount in her work.1

Wu’s idea to curate a community-based project that addresses environmental issues emerged in relation to a local problem. The environmental issue at stake was a polluted river, providing the title to her curator’s statement: Mending the Broken Land with Water: A Cultural Intervention at the Plum Tree Creek.2 What struck Wu was the degree to which the condition of a river could reflect the urban regeneration and local quality of life. Such was the case with the Plum Tree Creek, a tributary of the Tamsui River. The thought was this: if people accept a polluted creek, if they forget how the creek used to be, and if they have no awareness of the natural environment in which they live, then no vision for a better future quality of life is possible.

In fact, starting in 1994, several environmental art exhibitions went on display along the bank of the Tamsui River, becoming the first ‘off-site’ art to address environmental issues in Taiwan.3 These exhibitions, however, were designed for the public to see and reflect upon; there were no participatory elements in the making of these works. In addition, many government-funded art exhibitions or events were not programmed to run indefinitely. Local community members and other spectators were not invited to participate in the works; they were not given the chance to actively take part in shaping art projects or places. And although audiences were seeing objects displayed outside, they largely remained unaware of the connections between artwork, land and human landscape.4

New genre land art

Similar to Lacy’s idea of ‘new genre public art’, the Plum Tree Creek project is presented as a form of ‘new genre land art’ in order “to be regarded as a practice of artistic ecological rehabilitation.”5 The project must above all be sustainable within the community. The project offers a series of events to open up questions and invite people to contemplate the ways in which their lives relate to the river. There are five subprojects: Breakfast at Plum Tree Creek, Community Theater, Local Green Life, The Creek in Front of My School and The Nomadic Museum. The project also includes an educational forum through artist-in-residence schemes and workshops whereby school pupils, university students and local residents can interact and discuss with each other. The artist-in-residence scheme, a component of the Creek in Front of My School that is hosted by the Bamboo Curtain Studio and local schools, has provided a platform offering a significant participatory potential for educators, young people of different age groups, parents and students alike.

The subproject Breakfast at Plum Tree Creek, led by Wu Mali, is another telling example of participatory work, consisting of regular breakfast meetings and gatherings during which participants are invited to cook and eat seasonal foods from local farmers. Sharing a common interest for food allows people to sit and discuss, with local farmers included. The process helps to make participants more aware of their local environment.

The other subproject, Shaping of a Village: The Nomadic Museum Project, led by Professor Jui-Mao Huang and his students from the Department of Architecture at Tamkang University, focuses on community lifestyles and tries to revive the practice of ‘handicrafts’ amongst residents who, for the most part, moved from urban areas to settle in this cheaper area. The idea of a Handcraft Market has also been used to foster interactions between craft people, residents, visitors, as well as with the local and natural environments.

Sustainable awakening and the community’s cultural action

The Plum Tree Creek project has run since 2010 and was awarded the Taishin Contemporary Art award in 2013. The project has fostered discussions and attracted attention from the art scene in Taiwan; it has shown the extent to which art can transform a community for the better and awaken people to environmental issues, such as water pollution, in a sustainable fashion. It has highlighted the importance of eco-wellbeing and its relevance to metropolises such as Taipei as a possible response to serious environmental problems. The Plum Tree Creek project’s ‘new genre land art’ has a sustainable social impact through interaction. The project is by nature relational, dialogical, participatory, and, to some extent, comparable to Joseph Beuys’ ‘social sculpture’6 with its environmentally drawn awakening dimension, which invites willing participants and all people concerned to creatively reshape our environment accordingly for a sustainable, better future life.7 This participatory project has proved to be more efficient in addressing those issues in a sustainable way than government funded projects such as the ‘Taipei Public Art Festival’ in the years 2000s, or even the 1990s ‘Environmental Art Festival’.

The impacts of globalization and urbanization are obvious in the area of New Taipei City. It is a place where developing that sense of local character and awareness of environmental issues in the community is critical to maintaining the quality of life that allows a healthy balance between human and natural landscapes. Art as Environment: A Cultural Action at Plum Tree Creek project in New Taipei City is a typical example of a successful experiment of ‘social sculpture’, in Beuys’ sense, and of conversation-based participatory practice in the community. The project has gained attention in numerous publications and debates not only in the field of contemporary art, but also amongst community movements and environmental protection groups. Most importantly, the project has managed to address issues at the levels of both the particular and the universal: it highlights the deteriorating state of the local river and waters as well as addresses global issues of pollution in the residential area of an over-developed city. Wu Mali has not only been involved in the Plum Tree Creek Environmental Art Project as a curator and artist; she is also from the local community herself. As such, the project has concretely raised issues of community governance and engagement to allow for sustainability. The project has been conducted in a way that local people have been empowered through environmental awakening, a strong sense of communal reciprocity and mutual trust. Indeed, such civic action and engagement can set the example for many other urban areas and communities.

Wei Hsiu TUNG, Assistant Professor, Department of Visual Art and Design, National University of Tainan, Taiwan (weihsiu@hotmail.com).