Arief Budiman and his Family: Cultural politics under Guided Democracy

Arief Budiman was appointed as the Foundation Professor of Indonesian Studies at the University of Melbourne in 1997, holding the Chair until his retirement in 2008. This essay provides an overview of him and his family in the political and cultural context of what Sukarno, Indonesia’s first President, called Demokrasi Terpimpin (Guided Democracy).

Arief’s original name was Soe Hok Djin, but for convenience here Arief Budiman will be used throughout. (He changed his name in 1967 with his marriage to Leila Chairani Baharsyah.) In discussing the Soe family, the focus is on Arief himself, his father Soe Lie Piet, and his younger brother Soe Hok Gie. These three men were all precocious readers and writers. They were all ethnic Chinese born in Jakarta in the 20th century, oriented to the land in which they were born, and not at all oriented to China. None of them was Dutch-educated.

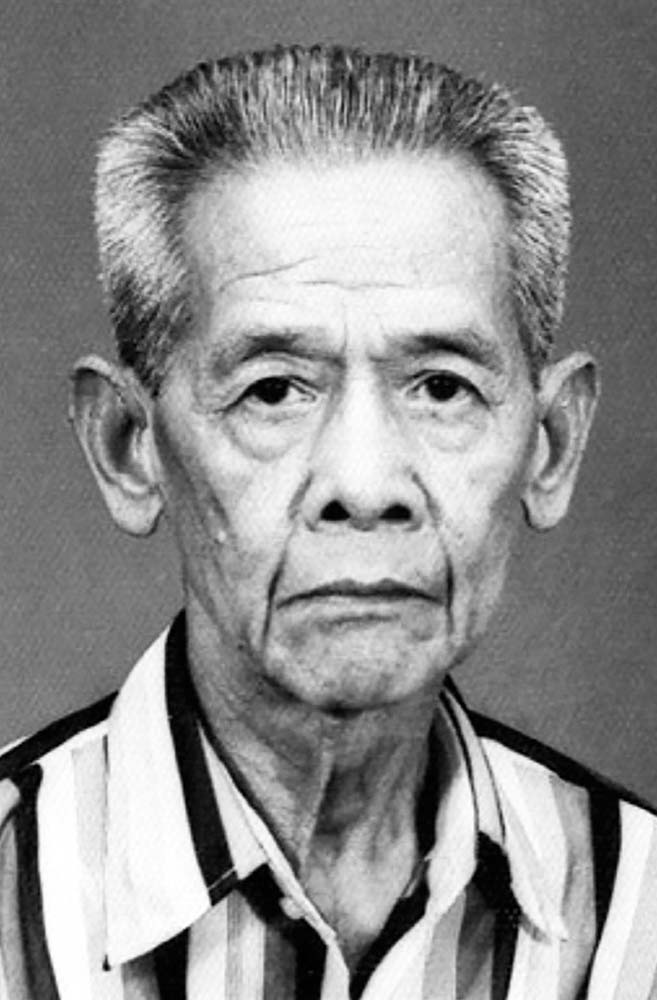

Fig. 1: Soe Lie Piet, 1982.

Arief later described the family in which he grew up as “lower middle-class” with “no academic background whatever.” His father Soe Lie Piet [Fig. 1], a writer and journalist, was often “unemployed or only half-employed.”

There are some important generational differences between Soe Lie Piet and his sons. Soe Lie Piet (1904-1988) grew up when the colonial Netherlands Indies was at its height, while his sons were the product of the Japanese occupation and the turmoil in which the Indonesian Republic was born. Although Soe Lie Piet was brought up in the household of his grandfather, an immigrant from Hainan, he was cared for and indulged by his maiden aunts, who spoke the Malay language typical of peranakan Chinese in Jakarta. His schooling was in an ethnic Chinese environment, primarily in the Tiong Hoa Hwe Koan (THHK) school, where he was instructed in Mandarin Chinese and later in English. From the 1930s he became a prominent Chinese Malay writer of popular romances in which the leading characters were Chinese, although the settings were often in different parts of the Indies and influenced by local magical and mystical beliefs.

His sons were brought up in a Malay-speaking home in Kebon Jeruk, an ethnically mixed part of Jakarta with a significant Chinese component. When they were young, their mother read them Chinese Malay stories, leading them to seek out comic books and then more serious reading from nearby lending libraries. Almost all of their schooling was in the new national language (bahasa Indonesia) with an Indonesian curriculum. They were taught to speak and write standard Indonesian and to avoid the kind of Malay that their father had used professionally. They may have found their father’s stories an embarrassment, both in terms of style and subject matter, if they had bothered to read anything he had written.

Soe Lie Piet was apparently never interested in politics, let alone politically active. In later life he withdrew into an introspective absorption with mysticism and the supernatural at a time when his two sons were becoming politically aware and active, taking courageous public stands on matters of principle. Their own writing engaged with politics at the national level, and they were both secular in outlook.

In his twenties, however, Soe Lie Piet had been a man on the move in search of employment as a journalist and writer. This took him to Medan and Palembang in Sumatra, to Surabaya in East Java, and to Bandung in West Java, where he married Nio Hoei An in 1933. In August 1934, they moved to Bali with a baby daughter, living there for nearly a year while Soe Lie Piet acted as correspondent for several Java-based publications. He also wrote several works based on his experiences there, including what were probably the first guides to Bali written in Malay, both published in 1935. His travels in search of gainful employment led him to places that also inspired several of his novels or short stories. 1

After Bali, the family moved to Jakarta, where their second daughter was born in 1936, followed by their first son Soe Hok Djin (Arief) in January 1941. Although Soe Lie Piet published several more novels, the family’s economic position soon became precarious. Under the shadow of war, his wife and her children returned to her mother’s house in Bandung, while he stayed in Jakarta. In 1941, he joined the editorial staff of the newspaper Hong Po. During the occupation, Hong Po urged the Chinese community to support the Japanese war effort. There is nothing to suggest that the apolitical Soe Lie Piet himself was pro-Japanese, but the job gave him some protection at a time when prominent Chinese journalists were interned or went into hiding.

In 1942, his wife and children returned to Jakarta, for Soe Lie Piet at last had found a simple timber house in Kebon Jeruk, which would be the family home for the next four decades. Soe Hok Gie was born there in December 1942 and lived there until his death a day before his 27th birthday in December 1969. Kebon Jeruk was the neighbourhood where both brothers lived throughout their schooling and university years.

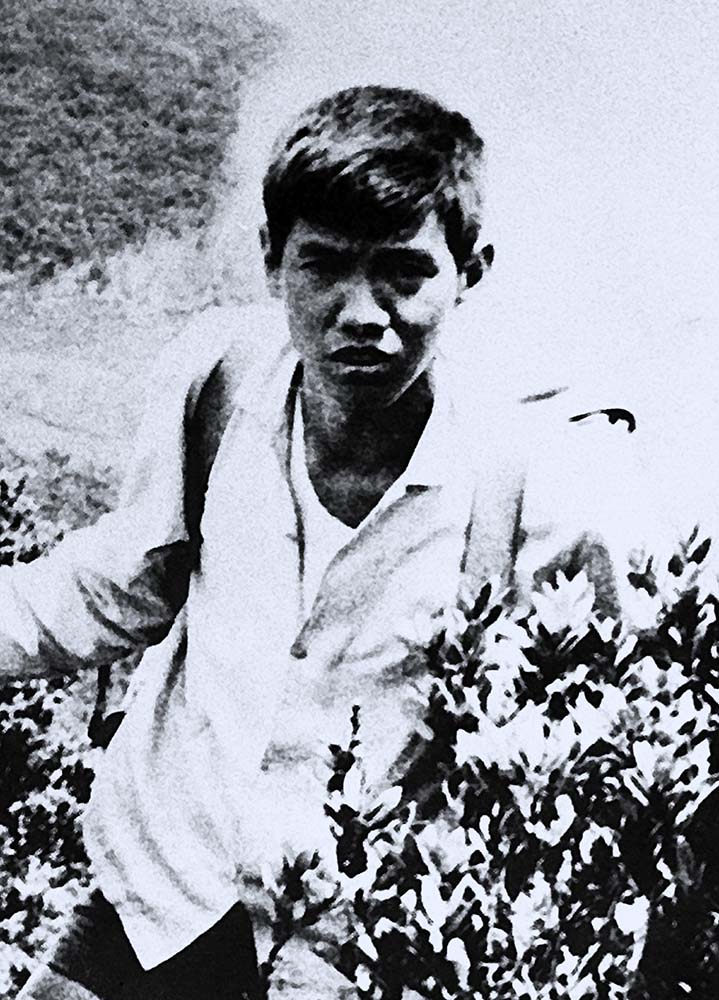

Fig. 2: Arief Budiman in Canberra, 1997.

Arief lived on for another half century after his brother’s death [Fig. 2]. It is an extraordinary and sad irony that when Arief died in Semarang on 23 April 2020, the headlines in the Indonesian press almost universally referred to him as Soe Hok Gie’s older brother. Soe Hok Gie seems to have had an afterlife as an almost legendary figure [Fig. 3]. Why was this so? First, he had started to keep a diary in early 1957 at the age of 14, and an edited version was published in 1983. 2 The final entry is 6 December 1969, ten days before his sudden death from toxic gas near the summit of volcanic Mount Semeru. The diary is a fascinating insight into the maturing mind of an intelligent young man whose life was cut short prematurely. Then, in 2001, John Maxwell's biography of Soe Hok Gie was translated, published, and widely read in Indonesia. 3 Finally, in 2005, Riri Riza’s partly fictionalised biopic film Gie was released, receiving three awards for best film, best leading actor, and best cinematography at the Indonesian Film Festival. The public attention given to the short life of Soe Hok Gie through the film, the publication of his diaries, and the detailed biography help to explain those headlines when Arief died. 4

Fig. 3: Soe Hok Gie, approx. 1968.

The two brothers were close in age and experience but were clearly very different in several ways. Although Arief was the older by nearly two years, they were contemporaries at school and university. They were in the same class at primary school, completing in late 1955 with such high grades that they were able to apply for admission with reduced fees to the best secondary schools in Jakarta. Arief attended the prestigious Jesuit Canisius College throughout his secondary education, but Hok Gie was only there for the last three years. Arief was in the science stream while Hok Gie was in the humanities.

Their academic performance at Canisius enabled them to gain entry to the elite University of Indonesia in late 1961. Arief went to the Faculty of Psychology at the main Salemba campus, and Hok Gie to the Faculty of Letters at the Rawamangun campus. These separations – different lower secondary schools, different streams at Canisius, and different Faculties at the University of Indonesia – went beyond different developing interests. They also reflected an estrangement that lasted a decade, in which the two brothers virtually stopped speaking to one another.

At Canisius and the University of Indonesia, the brothers may have been to some extent outsiders, but not because they were ethnic Chinese. Neither was ever attracted to joining an association defined by their Chinese ethnicity since they clearly regarded themselves as Indonesian. Their socio-economic background was probably lower than most of their peers, but at the same time they were unusually well read and intellectually sophisticated for their age. They made strong friendships with those who shared their interests.

The political context of “Guided Democracy”

In 1959, using a Presidential decree, Sukarno returned Indonesia to the 1945 Constitution (which was weak on human rights and strong on presidential power) in a system he called “Guided Democracy.” In 1960 he suspended the elected parliament and replaced it with appointed members. No further elections were held. Unelected himself and with the backing of the military, Sukarno ruled by decree, using ideological formulas and slogans to silence opposition and to ban critical media. The move to an authoritarian state grew over years, but from late 1963, with the support of the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI) and radical nationalist parties, Sukarno promoted a strong turn to the left. Any person or institution whose loyalty was doubted was subjected to demands for “retooling.”

In many respects the late Guided Democracy regime embodied a personality cult. Sukarno was beyond public criticism, and in May 1963 was made President for Life by a body he had himself appointed. Those newspapers that were still allowed to appear were required to include extracts from his writings. Anti-communist Indonesians with close Western connections were under attack, especially if they dared to challenge the PKI or organizations close to it by trying to persuade the President to take a less leftist or authoritarian position. Arief Budiman and Soe Hok Gie moved in these circles during their university student years, and each took a public stand contrary to the increasingly radical spirit of the times.

There were two very large organizations that are relevant to this discussion, which were closely associated with Sukarno and the PKI. The first was LEKRA (Lembaga Kebudayaan Rakyat - Institute of People’s Culture), claimed in 1963 to have 200 branches and 100,000 members. LEKRA took the “socialist realist” line that Indonesian culture should express Indonesian identity and serve the mass of the Indonesian people. It worked to suppress art and writing that failed to conform. The second was Baperki (Badan Permusyawaratan Kewarganegaraan Indonesia - Consultative Body for Indonesian Citizenship), established as a broad-based organization in 1954 to promote Indonesian citizenship for ethnic Chinese and oppose racial discrimination, and claiming a membership of over 280,000 by 1965. Under the leadership of its leftist chairman Siauw Giok Tjhan, Baperki supported Sukarno’s Guided Democracy and and was widely regarded as a member of the “progressive revolutionary forces.”

Arief, Sastra magazine, and the Manifesto Kebudayaan

When Arief entered the Psychology Faculty in 1961, he startled other students by discoursing on Jean-Paul Sartre and existentialism when he underwent the customary initiation process for new students. In fact, he had already translated a chapter of Albert Camus’ novel L’Etranger into Indonesian. Arief had a passion for Camus. According to his friend and fellow Psychology student Goenawan Mohamad, Arief’s anti-Utopian worldview and determination were strongly influenced by Camus’ book on The Myth of Sisyphus. He was already able to mix easily with established artists and intellectuals, and it was Arief, the boy from Kebon Jeruk, who introduced Goenawan to such circles.

In May 1961, the first issue appeared of Sastra, a literary magazine under the leadership of HB Jassin. Arief and his friend Goenawan were both contributors to the magazine, which was soon subjected to a sustained attack by LEKRA and other leftist writers. Indonesia’s most famous novelist, Pramoedya Ananta Toer, accused Sastra of having a bourgeois character and slammed those like HB Jassin who sought “to seek shelter from the tumult of the revolution, and to lull themselves to sleep with the theory of ‘universal humanism.’” In 1963, Sastra awarded Arief a prize for his essay on “Man and Art.” The twenty-two-year-old Arief was a potential target.

In August that year a group of anti-communist artists and intellectuals issued a Cultural Manifesto (Manifesto Kebudayaan). Many of the signatories were writers, including Arief, Goenawan, and Jassin. It was intended as a statement of their beliefs and aspirations for Indonesian national culture, based on the principle of freedom of expression in art and literature and what they described as “universal humanism.” The Manifesto was derided by LEKRA and their supporters, who gave it the derogatory acronym “Manikebu” (“buffalo sperm”). A full-scale culture war broke out with calls for it to be crushed. On 8 May 1964, President Sukarno issued a decree banning the Manifesto. Calls followed for a purge of counter-revolutionary forces from all educational institutions. Jassin was removed from his lectureship at the University of Indonesia and Sastra ceased publication.

The young student-philosophers Arief and Gunawan were not prime targets of this campaign but nor were they completely safe in this increasingly restrictive environment. Thanks to their international connections, they were each in turn able to escape and gain safe haven for a while in Europe. The Congress for Cultural Freedom had set up a committee in Jakarta in 1956, which offered scholarships for study in Europe. Arief secured such a scholarship in 1964 and went to Paris and the College of Europe in Bruges, Belgium. The Congress continued the scholarship for a second year, and this time the choice was Goenawan, who left Indonesia just days after the dramatic events in Jakarta on 1 October 1965.

Soe Hok Gie and the assimilation movement

When Soe Hok Gie became a student in the Faculty of Letters at the University of Indonesia in late 1961, he met fellow history student Ong Hok Ham (1933-2007). Ong had written a series of articles in Star Weekly about the situation of the Chinese community in Indonesia. These culminated in February 1960 with an article arguing that the only way for the Chinese to overcome prejudice and discrimination was for them to “assimilate” themselves into the majority Indonesian population.

In late March 1960, a group of ten Chinese Indonesians published a Statement in Star Weekly under the heading “Toward a Proper Assimilation.” It was a provocative document. It quoted the President as approving intermarriage between Indonesians of different ethnic groups, and a statement by Baperki chairman Siauw Giok Tjhan that solving the minority problem by name-changing and biological assimilation was unwise, undemocratic and violated basic human rights, implying that Baperki was trying to impede the process of assimilation. As controversy mounted and the assimilation movement developed, Hok Gie was drawn in through his friendship with Ong. This was made easier because he had never been involved in exclusively Chinese organizations and also because of his own modest class background. In addition, many of the assimilationists had Indonesian Socialist Party (PSI) or Catholic connections, like Hok Gie himself.

On 22 February 1963, Hok Gie was one of a small group of assimilationists who visited President Sukarno to seek his endorsement for their activities. He had no suitable clothes, but a jacket several sizes too large was borrowed for the occasion. Sukarno gave them a statement that they were happy to use against Baperki.

This achieved, the President regaled the group and members of the palace circle with political gossip and talk about sex. Hok Gie had never been a fan of Sukarno, but he was even more appalled by the evidence of the President’s lechery and venality – all duly noted in his diary. The President, however, was impressed by him, and later offered him a position in a history museum planned as part of the National Monument in central Jakarta. Hok Gie ignored the offer.

On campus, Hok Gie was active in the small Socialist University Students Movement (Gerakan Mahasiswa Sosialis - GEMSOS). They formed a study group in which they were addressed by prominent PSI-connected intellectuals, although GEMSOS was not formally affiliated with the banned PSI. Hok Gie was unimpressed by a number of the older PSI figures, who lived comfortable bourgeois lives. He dismissed them as “salon socialists.”

From his diary entries it is clear that his opposition to communism and totalitarianism was influenced by early exposure to the writings of ex-communists like George Orwell and Arthur Koestler. Despite this, he had some admiration for aspects of the PKI: its radical reform agenda; its attacks on big business, bureaucratic capitalists, and official corruption; and the reputation of its leaders for dedication, hard work, and moral probity as compared to other political figures.

Soe Hok Gie was very wary about stepping into the political arena. In a diary entry on 16 March 1964 he wrote:

In politics morality doesn't exist. As far as I'm concerned politics is something that's utterly dirty, it's filthy mud. But at a certain moment where we cannot restrain ourselves any further, then we will leap into it. Sometimes the moment arrives, as it did previously in the revolution. And if by some chance this moment comes I'm going to leap into this mud.

When the cataclysmic events of 1 October 1965 erupted in Jakarta, Hok Gie was actually with a group of his hiking friends heading for the slopes of Mount Merapi in Central Java. It was only after several days that they heard the news of the attempted coup against the army leadership and of the showdown between the army and the PKI that was underway.

Upon his return to Jakarta, he joined with a militant Islamic youth group in ransacking and burning of buildings associated with the PKI. By early 1966, he was an active leader in student demonstrations on the streets, expressing the Tritura (Tri Tuntutan Rakyat - Three Demands of the People): calling for the President to ban the PKI, to reshuffle the Cabinet, and to lower the price of basic commodities. This was part of a wider campaign by the newly formed KAMI (Kesatuan Aksi Mahasiswa Indonesia - University Student Action Front), but his group of campus-based students from the Faculties of Letters and Psychology acted both autonomously and in concert with others. Among other activities, the demonstrators took their protests to cabinet ministers and even to the President. This was a risky business because Sukarno was recalcitrant and tried hard to restore his authority, encouraging those still loyal to him to confront the protesters.

Arief was unable to take an active part in these demonstrations because he had fallen seriously ill with tuberculosis. Nevertheless, behind the scenes, he worked with a group of writers and artists preparing placards and posters that were used by the demonstrators.

After Sukarno was compelled to surrender powers to General Soeharto on 11 March 1966 and action was taken on the students’ demands, Hok Gie and Arief both engaged in preparing and writing scripts for broadcasts on the student Radio AMPERA. They worked together harmoniously and effectively. This was an important turning point in their personal relationship. The two brothers were also contributors to the two new student newspapers that appeared in mid-1966—the Jakarta daily Harian KAMI and the Bandung weekly Mahasiswa Indonesia—that were intent on attacking all aspects of the Old Order and its leadership.

In July 1966 the journalist and novelist Mochtar Lubis was released from detention. He had been visited in early March on several occasions while still in detention by both brothers who admired him for his principled opposition to Sukarno. Mochtar soon launched the magazine Horison, destined for a while to become Indonesia’s leading literary magazine. Arief (still under the name Soe Hok Djin) became a member of its original editorial board together with luminaries like the literary critic HB Jassin. At around the same time Hok Gie’s very first article in the press appeared in the student weekly Mahasiswa Indonesia under the title ‘Why I chose gaol – Mochtar Lubis and politics’.

Both brothers went on to become noted columnists in the mainstream press, particularly in Kompas and Sinar Harapan. But unlike many of their contemporaries, they did not remain silent in the face of injustices. In particular, Hok Gie’s two-part Kompas article in July 1967 on “The future social consequences of the Gestapu affair” was probably the first time that the horrendous scale of injustice and human suffering caused to the victims of the drive against the PKI and its affiliates after October 1965 was raised in the Indonesian press. In contrast to their friend Mochtar Lubis, both brothers took up the cause of the many thousands of political prisoners detained without charge or trial.

In the last phase of his life Hok Gie felt alone in his struggle. But as Arief stood beside his brother’s coffin in East Java, he declared “Gie, you are not alone.” Arief soon assumed the mantle of the activist, moving beyond the spoken and written word by leading campaigns against corruption, boycotting the stage-managed New Order elections, and opposing the expensive Taman Mini theme park.

Both brothers were public intellectuals who were steadfast in their courage and consistent in their defence of freedom of expression and human rights. We can only speculate about what Hok Gie would have done had he lived. In the case of Arief, during a period of graduate studies in the United States, he was influenced by a wider range of ideas, including neo-Marxism. When he returned to Salatiga, his teaching of development studies and contextual literature during the 1980s was anathema to some of his old friends and comrades.

Arief also came to regret the assimilationist movement and embraced the concept of a multicultural Indonesia in which Chinese culture had a place. He also recognised that the role of a public intellectual came at a cost to himself and his family. In his inaugural professorial lecture at the University of Melbourne, he paid tribute to his wife Leila, saying, “You all know it is far from easy to live as the wife of a person like me.” And yet, despite that statement to his dead brother – “Gie, you are not alone” – the title of that lecture was “The Lonely Road of the Intellectual.” 5

Charles A. Coppel, The University of Melbourne. E-mail: c.coppel@unimelb.edu.au

John R. Maxwell, biographer of Soe Hok Gie (see endnote 3). E-mail: johmaxwell@gmail.com