Appropriation and Misrepresentation of the "Indian Buddha Image" in Early Tang Buddhist Art

The transregional transmission of Buddhist art and culture has led to significant variations in form and function. However, numerous factors can affect the transmission of religious art and practice, complicating straightforward demonstrations of "inaccurate" transmission. This article highlights a rare and intriguing case from the early Tang Dynasty (618-690 CE): a Kṣitigarbha Bodhisattva statue located in Guangyuan, Sichuan Province, southwestern China. Its upper body closely resembles a seated Buddha in the bhūmisparśa mudrā (earth-touching mudra), as seen on several clay tablets inscribed with "Indian Buddha Image" that were excavated in Chang'an (present-day Xi'an), the Tang capital. The prototype for such a Buddha image can be traced back to Bodhgayā, northeastern India. While this appropriation of forms underscores the Tang dynasty's desire to adopt sacred images from Buddhism's Indian homeland, it also reveals that Tang artisans, especially those situated beyond the capital, had considerable freedom to adapt and reinvent the newly introduced exotic artistic canon.

The return of Buddhist monk Xuanzang 玄奘 (602-664 CE) from India to Chang’an (present-day Xi’an), the seat of the Tang court, in 645 CE marked a significant increase in interest in Indian Buddhism and its artistic traditions in the mid-to-late 7th century. A romanticized fascination with the birthplace of Gautama Siddhārtha, the founder of Buddhism, inspired Tang artisans to create Buddhist statues and murals imbued with the various Indian styles that were newly introduced along the Silk Road. 1 An intriguing example of such artistic recreation is Niche 17 of Cave 726 at the Thousand Buddhas Cliff in Guangyuan, Sichuan province, southwestern China [Figs. 1a-b]. In this niche, the artisans skillfully adapted the form features from a Buddha image originally from Bodhgayā, India, to represent a Kṣitigarbha bodhisattva. This appropriation of the Indian image, albeit with some misinterpretations, exemplifies the creative agency exercised by Chinese artisans in deploying their newly acquired exotic artistic language to craft new sacred imagery.

Fig. 1a-b: Kṣitigarbha, Niche 17, Cave 726, Qianfoya, Guangyuan. H. 122cm. 7th century. (Photo and line drawing by the author)

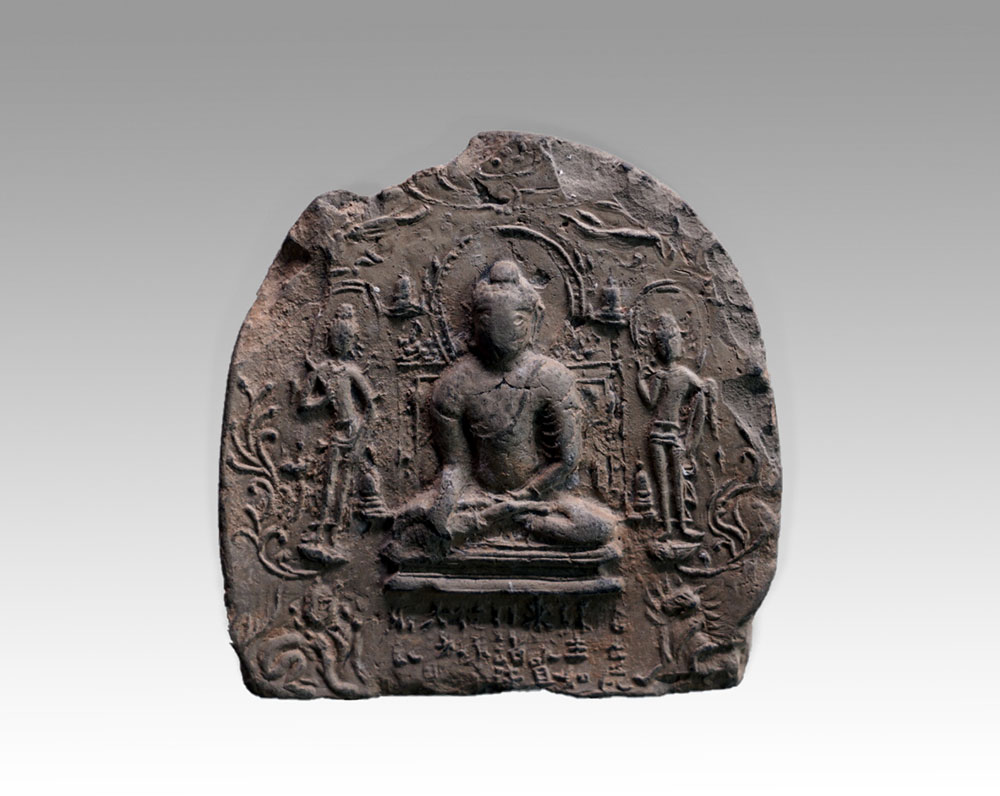

The Kṣitigarbha statue under discussion is depicted with the left hand placed in front of the abdomen and the right hand resting on the knee. This gesture contrasts with other Kṣitigarbha images but resembles contemporary Buddha statues found in Guangyuan, which are depicted in bhūmisparśa mudrā. Both the Kṣitigarbha and these Buddha figures are depicted wearing thin monastic robes that reveal the contours of their bodies, closely linking them to the "Indian Buddha Image" clay tablets unearthed in Chang’an. These tablets feature a seated Buddha in bhūmisparśa mudrā , flanked by two standing bodhisattvas on the front, and bear a dedicational inscription on the rear that states "Indian Buddha image commissioned by Su Changshi and Putong of Great Tang." Hida Romi has convincingly dated these tablets between 650 and 670 CE based on the activities of the commissioners. 2 Similar plaque discoveries across South and Southeast Asia are all believed to have been inspired, albeit perhaps indirectly, by Buddha statues enshrined in the Mahābodhi Temple in Bodhgayā, depicting the moment when the historical Buddha attained his first enlightenment. The Buddhist statues in bhūmisparśa mudrā [Fig. 3] from the 8th century, housed in the Indian Museum, Kolkata, not only retain identical attire and mudras (hand gestures) but also the cushions behind the statues. All of these factors provide valuable insights for tracing the prototypes of the "Indian Buddha Image."

Fig. 2: "Indian Buddha image", Ci’en Si, Xi’an, Shaanxi. Mold-pressed clay tablet, 7th century. Collected by National Museum of China. Photo by the author.

The cushion placed behind the Buddha, known in Chinese as yinnang 隐囊, is typically adorned with tied ends encircled by lotus petals on each side. This particular motif is prevalent in Buddhist statues throughout the Indian subcontinent but is rarely found in Chinese Buddhist sculpture. The cushion depicted in the "Indian Buddha Statue" clay tablet from Chang’an represents a rare example, although it has undergone significant simplification, with the tied ends shaped into two semi-circles adorned with a beaded pattern. The Kṣitigarbha statue in Niche 17 of Cave 726 at the Thousand Buddhas Cliff in Guangyuan features a mandorla with two cloud-shaped patterns analogous in placement to the cushion in the "Indian Buddha image" tablet. This mandorla, resembling the shape of the cushion with protruding tied ends, likely represents a misinterpretation of the original Indian design. Interestingly, a similar error in transregional transmission is also present in the Tangut-era Cave 465 in the Mogao Grottoes in Dunhuang. In Cave 465, the cushion-shaped backscreen painted behind a bodhisattva holding a flower mirrors the "cloud-shaped mandorla" of the Kṣitigarbha statue in Guangyuan. 3 This repeated mistake in artistic replication across thousands of kilometers, in addition to the substantial temporal gap between the two examples, highlights the challenges and complexities inherent in the dissemination and localization of Buddhist art in the Pan-Asian area.

Fig. 3: Seated Buddha, Bihar, India. Stone, H. 74 cm. 8th century. Collected in Indian Museum, Kolkata. (Photo by LI Jingjie)

How should we interpret the appropriation and misrepresentation in the Thousand Buddhas Cliff in Guangyuan? Both Buddha and Kṣitigarbha are depicted wearing monastic robes, with cushions or mandorlas placed behind the statues. These formal similarities played a significant role in reinterpreting the "Indian Buddha image" as a Kṣitigarbha image. This is not an isolated case, there are also instances in Guangyuan where Buddha statues are carved with gestures originally used for bodhisattvas. For instance, some statues from the same period are depicted with one hand raised, forming a sharp V-shape with the forearm and upper arm – a gesture typically seen in bodhisattva images in Indian styles, similar to the flanking bodhisattvas on the "Indian Buddha Image" clay tablets. Therefore, the appropriation of the Kṣitigarbha image should not be viewed as a spontaneous act of creativity but in conjunction with how Chinese artisans utilized newly introduced image elements to create Indian-style Buddha statues in the early Tang Dynasty. This appropriation of features with an apparent disregard for the original iconographic cannon, specifically between Buddha and bodhisattvas, suggests that local artisans at that time may have had considerable freedom in the creation of sacred images with the new exotic style.

Yang Xiao 杨筱 is assistant research fellow at the Institute of Archeology, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. Email: yangxiao@cass.org.cn