The Antilibrary in the Pandemic

For my spring break in March 2020, I travelled from New York City to Florida to visit my partner with a week’s worth of clothes in a backpack. This was when I was a doctoral student at Columbia, working on South Asian literature and British imperialism. Little did I anticipate that that one week of spring break would extend, nearly unendingly, into two years and seven months, at the end of which I would not only survive a pandemic, a mighty hurricane, and a flood but also initiate The Antilibrarian Project on Instagram to commemorate the loss of the beloved paperbacks I would lose in the flood.

The day after I flew out of New York, the city was indefinitely locked down to maintain quarantine and contain the COVID-19 pandemic. Classes went online in late March, ushering in a sense of infinite space, time, and solitude without institutional obligations. No sooner had I settled into my partner’s apartment than I started taking long walks to the ice cream shop and local bookstores, like 2nd & Charles and Books-a-Million, all masked up. Every time I left the house, I brought back at least eight to ten used and new books. I borrowed 15-20 books whenever my partner visited the university library. I carefully searched online for used books in my free time before placing bulk orders. I ordered mostly mass-market paperbacks from Penguin, Oxford UP, Bantam, Signet, Vintage, Tor, etc. Whatever came into the house was thoroughly sanitized with disinfectant wipes and dried in the sunlight before being handled and shelved – a process that I perfected to the point of efficiency over months.

Spring stretched out into an endless summer. People started dying from the virus. I lost two family members and a very close friend.

I bought books to forget that the usual routine of my life was disrupted. I also bought books to celebrate co-habiting with my partner indefinitely for the first time in our decade-long relationship. As I could not leave the house, I invited the world into our living room and onto our bookshelves. My partner thought of this as my period of adjustment and overlooked the three new bookshelves in the apartment double-stacked with used mass-market paperbacks and hardcopies at the beginning of the Summer of 2020. At this point, we stopped alphabetizing our bookshelves.

Groceries, a tub of chocolate ice cream, along with a package from Thrift Books – these were our weekly deliveries from May to October of 2020.

Hurricane Season

Around late summer – hurricane season in Florida – I diligently started following all the major literary awards besides the annual Nobel Prize in Literature. The raging thunderstorms from the hurricane made me so nostalgic about the Calcutta monsoon that I started collecting all contemporary “Winners” of major global literary prizes and awards. This dramatically increased my ever-growing personal collection of unread but “important” books.

In September, I started participating in the “Great Plague Texts” reading group with my friends. I ended up buying those books that were omnipresent on the internet: Boccaccio’s The Decameron, Defoe’s A Journal of the Plague Year, Camus’ The Plague, Ma’s Severance, Roth’s Nemesis, Mann’s Death in Venice, and Saramago’s Blindness. The reading group ran for three weeks before getting disbanded by its founding members, who were suffering from excess sleep, restlessness, anxiety, and free time. More books started arriving at our doorsteps, and I got my first pair of prescription glasses. I felt like a real scholar, although the doctor said the excess ice cream might eventually affect my retina. But for the time being, there was nothing to worry about. Time was on my side.

Following the reading group’s shutdown in October, under the influence of the Southern Gothic spookiness of a North Central Florida college town, I undertook a brand-new project of making a catalog of the most notoriously celebrated books on Occultism, Witchcraft, Satanism, Wicca, Magic, Goetia, Demonology, Spells, and Alchemy. By March 2021, I had acquired nearly seventy significant works on this literature, mostly from my partner’s university library: de Spina, de Plancey, Nider, de Givry, Flamel, Paracelsus, Kramer, Levi, Michelet, Murray, Marwick, etc. We were both quite confounded to notice that a public school in a conservative “red state” would preserve such a fantastic collection of Occult literature. I read no more than three books to prepare myself for Halloween.

On All Hallow’s Eve, I read Shirley Jackson’s We Have Always Lived in the Castle for the first time. From the novel, I took away that a) sugar is poisonous, so I should stop ordering ice cream every alternate day, and b) sugar can be poisoned; therefore, I shouldn’t be eating so much ice cream.

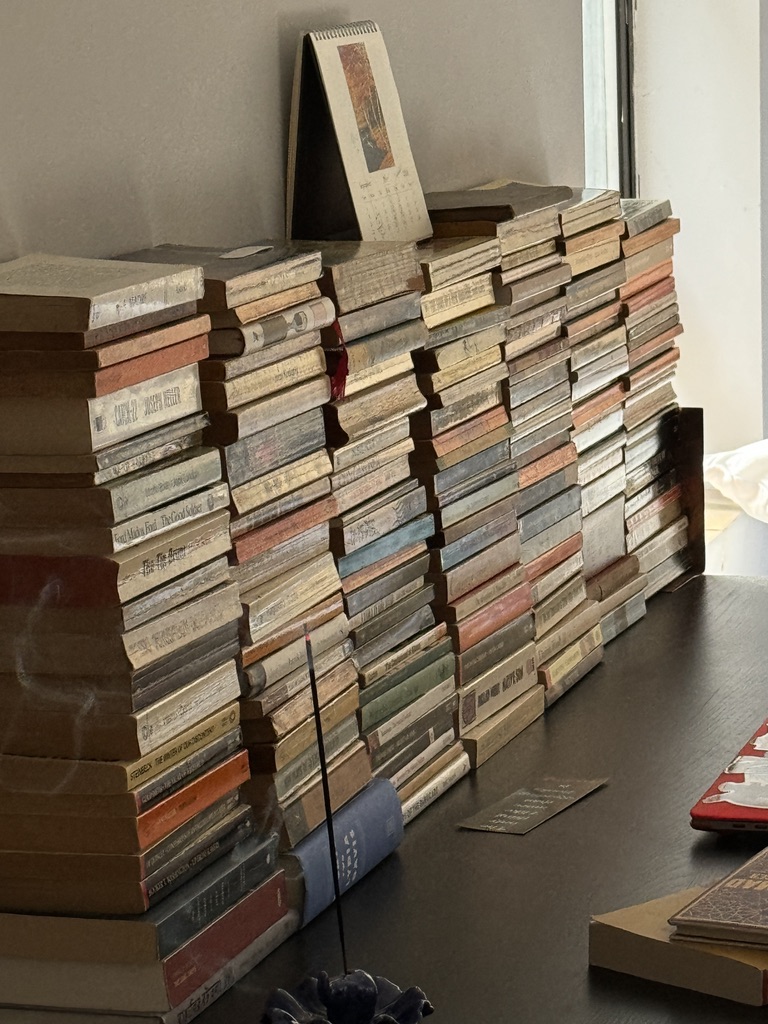

Following a December visit to New York, during which we acquired still more books, our one-bedroom apartment in Florida ran out of space to store these “necessary” paperbacks. Empty floor space was already occupied with stacks of books (Fig. 1), which we used as coffee tables and footrests.

Fig. 1: Stochastic Piles of Unread Books (Photo by author, 2021).

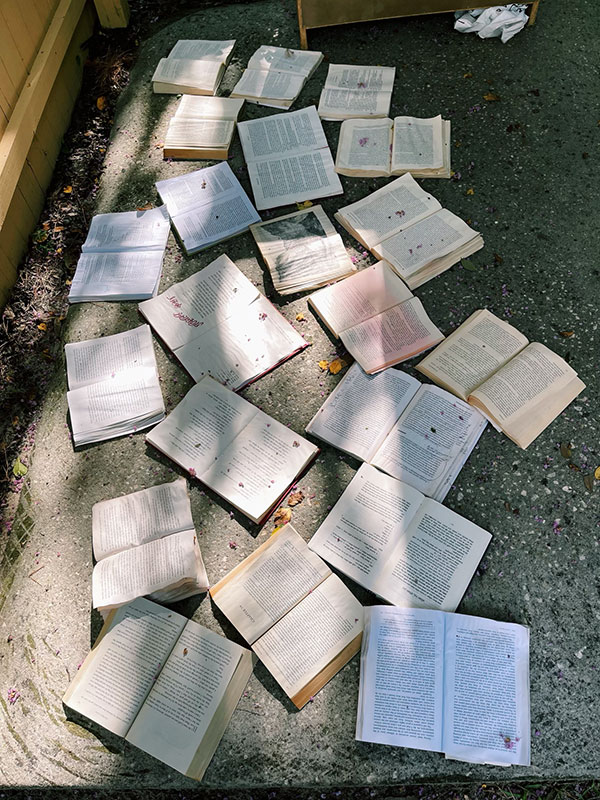

We transitioned from winter to spring to the summer of 2021 – hurricane season was upon us again. I bought very few books during those months. I was oversaturated. I lost two more family members. I ordered a copy of Fernanda Melchor’s Hurricane Season to celebrate the arrival of this violent monsoon in a foreign land. By the middle of Melchor’s book, I realized it had nothing to do with hurricanes or typhoons but with violence. Two days later, on 7 July, hurricane Elsa hit Florida in the morning and moved north and inland from the Gulf of Mexico. It rained all morning and afternoon. The tropical storm gradually became stronger in the evening. I was in the living room when water started filling our apartment from beneath the front door (Fig. 2).

The maintenance guy said that the two duck ponds adjacent to our apartment were flooded, which clogged the drains and caused the water to rise. We rushed to grab the books on the floor and throw them on the bed. The water inside the apartment rose quickly in ten minutes and flooded into the bedroom. Now, the water was up to our knees. It was not the filthy water that made us panic but the fear of snakes and baby gators that were notorious for infiltrating apartments during tropical floods. We grabbed our passports, immigration documents, laptops, and chargers and immediately evacuated the apartment, moving toward elevated ground. We left with our backpacks and a suitcase and stayed at a friend’s house for a week.

A week after we left, the sunny third week of July – so sunny that last week’s hurricane now felt like a distant dream – the apartment management informed us that the apartment was no longer habitable, so they would relocate us to a different apartment at a higher elevation. We returned to our flooded apartment to salvage our things. Management gave us two layers of industrial masks as a safety measure because black mold had appeared all over the apartment as the water dried. The manual workers who entered the apartment without masks developed allergies and infections, and management couldn’t be sure whether the virus or the fungus had made them sick.

We found most of the electric sockets in the apartment damaged. The walls were damp and soggy, like a waffle ice cream cone. The bathtub was full of strange fauna and debris. We found a giant snail merrily lingering in it. All the books on the lower two shelves of the bookcases were damaged, moldy, and disintegrating. The cardboard box under the bed filled with dissertation notes, research materials, notepads, and paperbacks lay blasted open.

That evening, we threw nearly 200 books beyond repair and rescue into the dumpster. We tossed out the storage ottomans wholly submerged in water, two upholstered chairs, damp clothes in the closet, a faux-leather sofa, and most utensils under the kitchen sink. Our housing insurance did not cover “Act of God” events, meaning we had to rebuild our whole life from scratch.

After we relocated to the new apartment, we laid out approximately a hundred books on the patio to dry them under the sun daily for a month (Fig. 3). We couldn’t bring the books indoors because mold is airborne and easy to contract. If I fell sick, my university health insurance couldn’t cover out-of-state medical costs, nor would my partner’s health insurance have saved me because my partner was not my spouse. We were living in hell, in a moment of meta-paranoia. I was the most vulnerable person in the apartment, not immunologically but institutionally, infrastructurally, and legally.

Fig. 3: Moldy books drying in the sun (Photo by author, 2021).

By mid-August, I threw out sixty more books because the wet photo papers inside illustrated books were glued to one another and became one solid block of rock. The unpredictable showers in the mornings reversed the whole process of book restoration. By late August, we couldn’t remember which books we had discarded during the relocation. We realized that some of the library books were now missing. The libraries asked us to replace the books if we didn’t want to pay hefty fines. We started ordering books again online. Time was running in a circle.

The Antilibrarian Project

Around this time, I started clicking photos of all the books in the apartment to document the books we possessed – or that possessed us. Within two days, I took almost 2000 photos of individual books. The surest way to avoid running out of phone space was to upload the photos to an external cloud server like a social media account, albeit in lower resolution. As a result, I started “The Antilibrarian Project” (@antilibrarian) on Instagram.

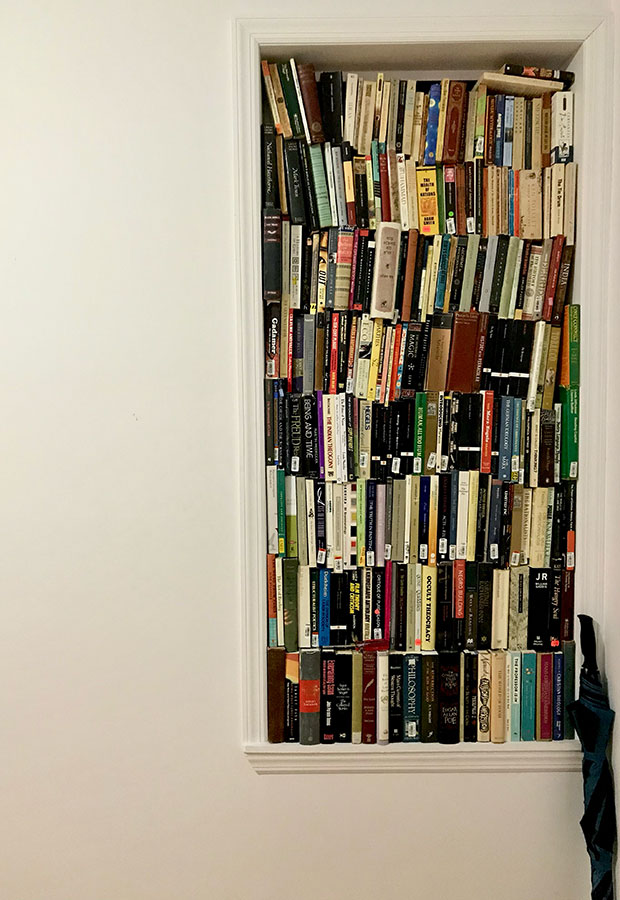

The handle was inspired by Nassim Nicholas Taleb and Umberto Eco’s concept of the “antilibrary,” which refers to a personal collection of unread books. For me, the antilibrary is more than just stochastic piles of unread books. It contains books bought, gathered, borrowed without returning, gifted, returned to us, hoarded, stolen, smuggled, rescued, serendipitously found, received, inherited, and even dreamt. The antilibrary shares the most intimate spaces with us. It lives with us; we go to sleep in its ever-awaiting presence and, therefore, also make love, bare ourselves, and express our deepest, darkest emotions in its proximity (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4: A Window of Books (Photo by author, 2021).

The antilibrary is also our personal memento mori: a constant reminder of the transience of life and the passage of time in the signs of the gathering dust. In its ever-growing, parasitic, and uncontrollable grotesqueness, the antilibrary is the microcosm that embodies a little bit of everything we ever want to know but will never come to know. The antilibrary is inextricably tied to the mortality of our flesh and intellect (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5: Stacks of mass-market paperbacks on the writing desk (Photo by author, 2024).

Being an immigrant in someone else’s country, the antilibrary is a perpetual reminder of my rootlessness and peripatetic lifestyle because I have to move with my antilibrary from one apartment to another every two years. Our rate of accumulating/hoarding/collecting books will always surpass our rate of reading them, which is the foundational principle of the physical and digital antilibraries. The antilibrary highlights the constraints and priorities of our existence on this planet: linguistic (because our antilibraries are translationally streamlined), archival (because thousands of years of esoteric commentaries on liturgy, orthopraxy, adoxography, and hagiographic accounts belong to an actual library being out of print), disciplinary (comprehensive literature on limnology and golf course management is missing in my antilibrary), ideological (there are texts we would never keep in our possession even if we have read them), and corporeal (my grandmother often wished for a third prosthetic hand because one was employed in holding the book and the other a magnifying glass). AI, machine learning, cloud servers, or hard drive space – where digitized books can be stored and sifted through in seconds – cannot boast of possessing antilibraries since they cannot help but read/skim/search through every digitized word and sign system on this planet. Machines are not cursed with human constraints.

I initially used The Antilibrarian Project to upload or “dump” photos of stacks of books to keep track of what I was buying. I was completely unaware of the ethics of operating a public social media profile. As I started spending more time on the platform, the global community of the so-called “bookstagrammers” (Book-Instagrammers) became visible to me through the vibrant networks of “Followers,” “Followings,” and “Suggested” accounts as well as through the user-generated cross-referencing hashtags (#) for the latest trending topics. Bookstagram is a space on Instagram that is algorithmically curated and produced by users interested in books and their manifold functions. This space promotes non-specialized and non-academic perceptions of the broadly conceived world literature – literature of the world and the world of literature. On the platform, exchanging ideas among diverse accounts is encouraged and cherished rather than shunned for being dilettantish.

During my first month on the platform, I posted photos of a literary text with a short caption describing the text’s overarching themes and storyline. The posts didn’t garner much attention due to the nascency of the account. As days passed, I started experimenting with the frequency of my posts, the camera’s lighting, contrast, highlights, saturation, depth, and the background against which books were photographed. I realized that the way a user treated these different elements of composition produced various bookstagram aesthetics, genres, and sensibilities:“dark academia,” “light academia,” “cottagecore,” “vintagecore,” “petcore,” “leisurecore,” “boomercore,” “cafécore,” etc. This is where bookstagram brings together fashion, architecture, travel, interior decoration, political intellectualism, activism, promotion of local booksellers and bookstores, cultural prejudices, and social aspirations. Posing with Irving’s The Legend of Sleepy Hollow in Sleepy Hollow in the Fall is “way cooler” than posing with it in the historic NYPL because books on social media are everyday commodities tied to aspirational lifestyle identities. One only needs to look to the nearly concurrent rise of “book stylists” and celebrity sightings including Bella Hadid carrying Camus’s The Stranger and her sister Gigi Hadid with King’s The Outsider. Books, the zeitgeist had declared, were the new “it” fashion accessory.

This superficial relationship to the medium of the book came with its unique faux pas and absurdities. I saw a user pose with Woolf’s Orlando in Orlando, Florida, thinking the novel was about that place. The second user expressed excitement over gifting Morrison’s Beloved to their beloved partner on their first anniversary as a token of unshakable love. The third user posed with Gordimer’s July’s People on a blue summer beach in July and posted a caption that more or less said: “Haters will always hate the people of July! Move on, haters!”

Adventures in the Bookstagram Wonderland

After three years of collaborating and engaging with other bookstagrammers, I observed a few critical things that we must urgently address if we want to revivify and expand humanities and liberal arts education worldwide:

- The Demographic Expectations: My captions on canonical texts – from Homer to Tranströmer – had only a niche audience among users aged thirty and above. Posts from this demographic showed users’ nostalgic memories of reading these texts in the last century. The users below thirty responded to these posts with: “Adding this to my TBR (To be read) list.” Clearly, they – from humanities academics, general non-academics, and non-humanities academics – considered reading canonical Global North texts aspirational but had no time to read them.

- The Role of Online Book Clubs: Significantly popular bookstagram accounts and online book clubs (like Reese Witherspoon’s book club @reesesbookclub, Kaia Gerber’s book club @libraryscience, and Oprah’s Book Club @oprahsbookclub) focus more on acquiring or buying books, not their actual circulation through libraries or lending systems. Public engagement in the book club format is created through a series of questions posed by the creator at the end of the 90-second-long reels, which persuade viewers to get a copy of their own.

- Curation and Politics: Bookstagram accounts do not only orchestrate the aesthetics of a physical antilibrary (like Gwyneth Paltrow’s recruitment of a “book curator” to decorate her house, as reported in The Town & Country magazine in 2019) but also create global subscriptions to particular political affiliations. For example, in May 2024, Ben Affleck’s daughter, Violet Affleck, was photographed by paparazzi walking with Steven Thrasher’s The Viral Underclass. The high schooler’s gesture soon became a commentary on mask mandates and our handling of the pandemic, as well as her political investments in issues like the genocide in Palestine, as reported by The Cut magazine.

- The Aesthetic Appeal: The book covers’ hijacking of mobile and laptop screensavers, wallpapers, display photos, and other mood boards on different social media platforms (e.g., Pinterest, Threads, or X) through “crossposting” features is a quintessential aspect of reading in the twenty-first century. Photos of casual stacks of books lying around enjoy the privilege of enhanced engagement.

- The Dominance of Global North Authors: Posting about prominent authors from the Global South still does not garner much traction and engagement as opposed to major and minor writers from the Global North, as literature in English is still the gold standard that determines shares, comments, likes, and reposts.

- Thin Fictions: There is a growing preference among users for sharing and promoting “thin fictions,” which has bigger fonts and are less than two hundred pages, like the works of Claire Keegan, Eva Baltasar, Annie Ernaux, Hiroko Oyamada, Alejandro Zambra, etc. Anything around or less than a hundred pages is called “wafer-thin fiction,” like Handke’s The Left-Handed Women, Forster’s The Machine Stops, Bellow’s The Actual, Tsushima’s Territory of Light, and more. Wafer-thin fiction has made narrative ever more bite-sized and easy to devour.

- Cats, Cafés, and Bookshops: Contemporary writings on cats, cafés and diners, and bookshops and libraries have a significant circulation on the Instagram algorithm. Contemporary Japanese authors mostly dominate this literature like Kawamura’s If Cat Disappeared from the World, Akiwai’s The Travelling Cat Chronicles, Hiraide’s The Guess Cat, Kawaguchi’s Before the Coffee Gets Cold series, Natsukawa’s The Cat Who Saved Books, Yagisawa’s TheMorisaki Bookshop series, Kashiwai’s Komogawa Food Detective series, Murakami’s The Strange Libary, Aoyama’s What you are looking for is in the library, etc. These narratives are appealing not only because they are slim volumes but because their rhetorical style is light and lucid, where the atmosphere and tone shift from gloomy, cozy, and snowy to fantastical. After all, cats in their manifold avatars – real life, representation, or prop – do wonders for the bookstagram algorithm!

Literary appreciation and aesthetic judgment have significantly shifted in the post-Covid pandemic world. The reading communities on social media exist simultaneously and contiguously with academia’s solitary reading spaces and practices. Their mutual symbiosis can no longer be ignored. Online reading communities are close to shaping university and college curricula, syllabi, canons, and disciplines. In the face of immense denigration and global defunding of liberal arts and humanities, we must radically consider these social media reading spaces where a book post can go viral across a worldwide community of readers in hours with the correct algorithm and caption hook. Teachers and academics will find it helpful to tap into this tentacular arachnid network of global reading communities on Instagram or TikTok and incorporate alternate systems of engagement to reanimate university course curricula and assignments. We must re-imagine traditions and canons of literature backward (if there are canons at all anymore) – paying more attention to social media, the post-pandemic generation of students, contemporary literary publications, online reading communities, and the dynamic technological and material infrastructures within which acts of reading become possible and political.

The Antilibrarian Project now has more than 27k+ followers, with posts occasionally going viral with half a million views. Through the engagement metric and account visibility, I regularly receive advance review copies from major publishers like Norton, Simon & Schuster, Viking, McSweeney’s, Scribner, Europa, Bloomsbury, Scribe, and more. This project is rooted in Instagram’s accessible interface and preference for the imagistic over the textual, through which the media application still retains a global fondness and aesthetic appeal for still pictures and moving images as dominant modes of communication. In the future, if Instagram and other such social media become obsolete, we will always have our antilibraries – the testaments to our collective curiosity and madness – which are infinite, inexorable, and parasitic because they are bound to take over our lives, and I believe we should let them, as they give purpose and legacy to our hoarding books.

Sourav Chatterjee is an Early Career Postdoctoral Fellow and Lecturer in the Department of Middle Eastern, South Asian, and African Studies (MESAAS) at Columbia University. Email: sc4247@columbia.edu