Across the Korea Strait and the Yellow Sea. Kim Ji Ha in the 1970s

Kim Ji Ha was a poet who resisted Park Chung Hee’s regime of developmental dictatorship in 1970s Korea. In 1970, he published a poem that criticized the military dictatorship, and the Korean government imprisoned him under the outrageous claim that he had violated the Anticommunist Law. After being released, Kim Ji Ha published another poem that sang of democracy, and soon returned to prison. His life in the 1970s was a cycle of imprisonment, release, escape, and arrest, and he was not able to publish his work in Korea until 1982.

Among the people who reached out to him in solidarity during his imprisonment were Japanese citizens. In the 1970s, around twenty collections of the works of Kim Ji Ha, a resistance poet of Korea, Japan’s former colony, were published by the people of Japan, the former colonial empire. Twenty is the number of official publications produced in the 1970s in Japan; this number skyrockets when pamphlets, newsletters, and pirate publications are included. The publication of Kim Ji Ha’s works in 1970s Japan was a movement of solidarity between Korea and Japan led by Japanese citizens as a campaign to support Kim Ji Ha. Japanese citizens, religious figures, literary figures, and Koreans in Japan participated in this movement. The Japanese citizens observed the process of Kim Ji Ha’s trials in real time while editing and publishing the various manifestos that he drafted, along with the records of his trials. As the oppression of Kim Ji Ha intensified in Korea, the power of solidary shown by Japanese citizens also strengthened.

When Kim Ji Ha was sentenced to death in 1974, Japanese and Korean-Japanese literati staged a hunger strike, and approximately a thousand Japanese citizens protested in front of the Korean Embassy in Japan. Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Howard Zinn, Edwin Reischauer and others participated in the International Committee to Support Kim Ji Ha, following the suggestion of Oda Makoto and Tsurumi Shunsuke. In June of 1975, Kim Ji Ha was awarded the Lotus Prize for Literature from the Afro-Asian Writers’ Association as a writer of a ‘free-world’ country; this was also due to the help of the Japanese literati. As a result of the solidarity and attention of Japanese citizens, the complete collection of Kim Ji Ha’s works was published in Korean and Japanese in 1975 and 1976, respectively. Given that the publication of Kim Ji Ha’s works had been prohibited in Korea, their publication in Japan as a result of the solidarity of Japanese citizens became a huge international incident.

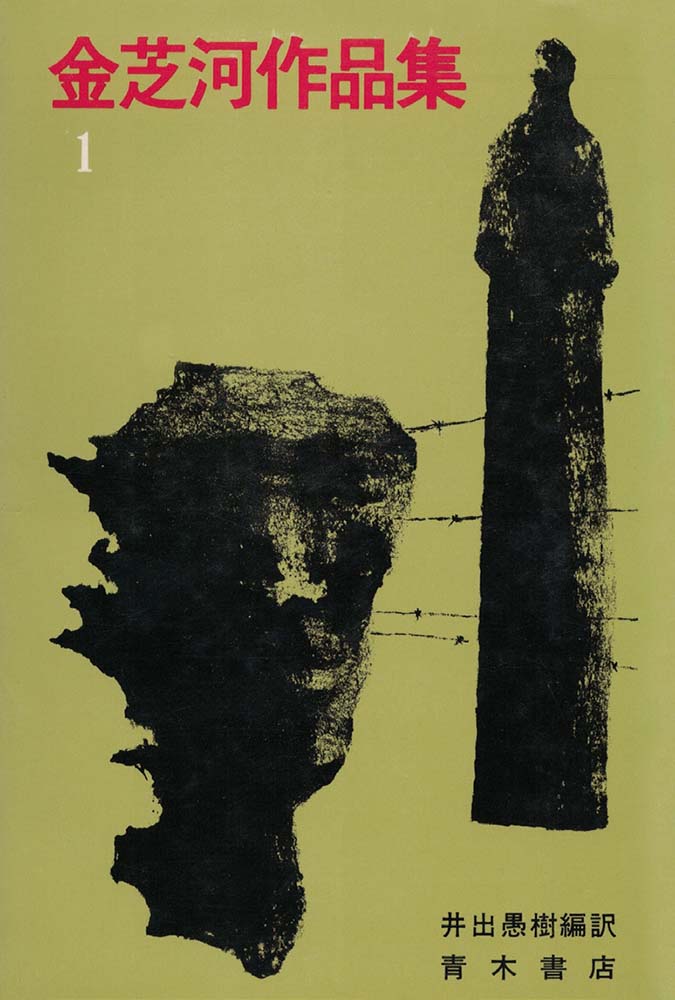

Collected Works of Kim Ji Ha (Vol. 1), published in Japan in 1976. The cover illustration is the work of the Japanese artist Tomiyama Taeko. Image of the original cover scanned by the author.

Some unexpected problems arose, however, in the process. As Kim Ji Ha – the ‘resistance poet’ of the former colony – was being helped by the citizens of the former colonial empire, Japan, for over ten years, a ‘relationship of aid’ became fossilized. While the stereotypes of Korea as an underdeveloped country of dictatorship, and Japan as a country helping the oppressed resistance poet, came to be reproduced, Kim Ji Ha’s literary themes of criticizing colonialism were no longer given due attention. Despite the fact that so many of Kim Ji Ha’s works had been published in Japan, it was only the sentiment that ‘Kim Ji Ha must be helped’ which flourished. The self-reflexive question ‘Why should I read Kim Ji Ha now?’ was omitted.

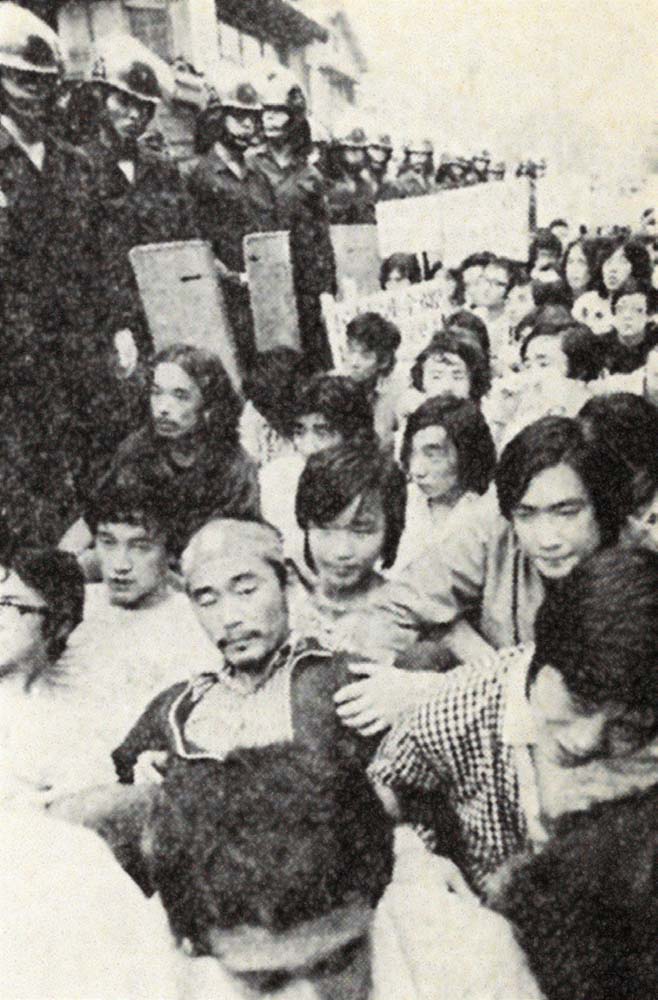

Japanese citizens demonstrating in front of the Korean Embassy in Tokyo in July of 1974. Image from Sanzenri Feb. 1975, scanned by the author.

The Chinese magazine World Literature also introduced a translation of Kim Ji Ha’s works in June 1979, in this case in association with the novel El Señor Presidente by Miguel Ángel Asturias, a Guatemalan writer. Both Kim Ji Ha and Asturias’ works shared the themes of dictatorship and resistance, allowing the reader to read the two together in order to grasp the universality and specificity of dictatorship in underdeveloped countries from a new perspective. This Chinese publication of Kim Ji Ha’s works illustrates the fact that reading East Asian literature alongside Central American literature can open up the possibility of imagining world literature in a new way. Yet, it should be noted that the Chinese translation utilized not only Kim Ji Ha’s original Korean works but also the versions that had been published in Japan. This shows how Japanese, the language of the former colonial empire, continued to play the role as a mediator in the process of East Asian communication, even in the Cold War era.

Kim Ji Ha in the 1970s remained immobile in South Korea due to imprisonment and dictatorship oppression. However, translated into Japanese and Chinese, his works were able to travel. The crossings of borders demonstrated by Kim Ji Ha’s works leaves us to ponder upon the task of solidarity of East Asian citizens and the conditions for such solidarity; it also opens the door to imagining world literature in a new way and the possibilities of this endeavor.

Jang Moon-seok, Assistant Professor, Department of Korean Language and Literature, Kyung Hee University imhwa@chol.com