Accidental Conservatives? Economic Technocrats and Modernization in New Order Indonesia

As a set of ideas, conservatism conjures certain images in our public discourses. In politics, conservatism is associated with resistance to progress, a defense of hierarchy, and a hidden predilection for authoritarianism. In culture, conservatism implies an attachment to tradition and norms, skepticism of recent trends, and morality policing. At its core, conservatism is a philosophy-cum-movement of reaction against egalitarian demands, marked by a high degree of pragmatism and flexibility. 1

What is sometimes missing in this conversation is the role of economic conservatism in sustaining conservative politics and cultural ethos. Without the implementation of conservative principles in economic realms, the sustenance of a conservative state and societal order becomes untenable.

The defense of a supposed natural hierarchy, according to the orthodox conservative thinking, requires a principled approach against the horrors of statist collectivism. In postwar Western conservative thought, this translates into a preference for market capitalism, which overlaps with the emerging neoliberal faith in the free market. The works of economists such as Friedrich Hayek, Milton Friedman, and James M. Buchanan featured prominently in conservative political circles. These were embraced by campus activists, intellectuals, political operators, and the highest echelon of leaders such as Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher. Despite severe methodological disagreements among the three economists – Friedman believed in empirical positivism, while Hayek and Buchanan preferred a more wide-ranging, social theory approach – they all hailed the virtue of the free market and formulated political and moral justifications for it. 2

But what if this opposition against statist collectivism originated from a more incidental conjuncture? What if the ideational inspirations for such an opposition were more eclectic? What if the proponents of this idea, inadvertently, embraced conservative politics? This is exactly what happened in the Global South. In her creative investigation on the entangled histories of midcentury Colombia and the United States, the historian Amy C. Offner shows how ideas and policies developed and implemented under the zenith of developmental and welfare state eras were later refashioned and repurposed – in her words, “sorted out” – to tear down such paradigms and pave the way for neoliberalism. 3 In modernizing parts of Asia such as Japan, Taiwan, and the Philippines, (limited) land reform was instituted after the Second World War as a bulwark against agrarian radicalism and Communism.

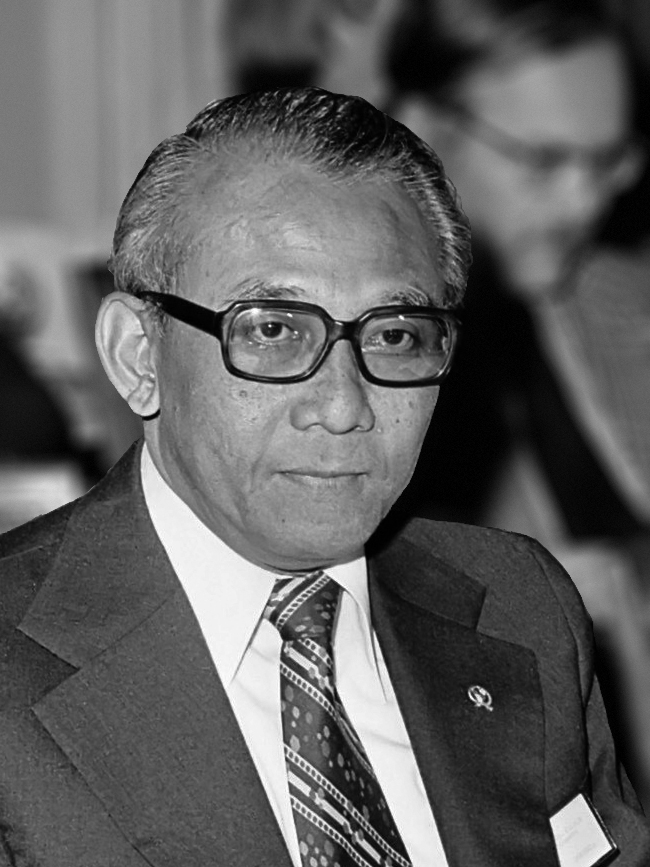

This essay focuses on three major technocrats: Ali Wardhana (1928-2015) [Fig. 1], Widjojo Nitisastro (1927-2012) [Fig. 2], and Emil Salim (b. 1930) [Fig. 3]. These US-educated economists – famously known as the Berkeley Mafia – served as ministers for the New Order government, oversaw its capitalist reforms, and engaged with the public as educators and public intellectuals. They were not “classical” conservatives in the Western sense, but the élan vital of their vision was conservative, rooted in the fear of destructive “ideological” mobilization and, in contrast, in a faith in the “rationality” of capitalist planning. Their engagement with and later embrace of conservative politics was a result of political necessities in the context of authoritarian consolidation. Therefore, they are best described, I would argue, as accidental conservatives.

In this context, studying the lives and thoughts of these economic technocrats who served the authoritarian New Order government (1966-1998) becomes a crucial endeavor. Caricatural descriptions of the technocrats depict them as either saviors of the Indonesian nation or intellectual stooges of imperialism. There are some truths in these accounts – the technocrats stabilized the Indonesian economy for rapid capitalist development and had close links with Western financial and development institutions. But they overlook the complexity and nuances of economic ideas, political and emotional motives, and the agency of the technocrats.

From an analytical standpoint, reducing the oeuvres of the technocrats into simple categories risks losing sight of the broader resonance and novelty of their thinking. Their ideas, actions, and policies were not lesser copies or cheap imitations of Western conservative and neoliberal economic and philosophical thought. There is a degree of sophistication in the technocrats’ brand of economics that we should admit and grapple with, regardless of one’s political affiliations. Studying the parallels and divergences of their thinking with Western economic conservatism will allow us to better comprehend the novelty and creativity of a major strand in conservatism in Indonesia and the Global South.

Equally important, understanding the complexity of their brand of conservatism and its policy implications will help progressive social movements, activists, and intellectuals to know their political rivals better and formulate alternative economic policies beyond mainstream economic prescriptions.

The prelude: Sukarno’s Guided Democracy (1959-1965) and its bourgeois opposition

Guided Democracy emerged as a response to the instability of Indonesia’s early experimentation with parliamentary democracy (1950-1959), a noble undertaking tainted by the political elites’ constant jockeying, regional rebellions in resource-rich provinces, and the reluctance of the state and capitalist class to accommodate labor demands.

Impatient with the liberal democratic procedures, Sukarno and the Armed Forces installed the Guided Democracy government, which was led by Sukarno and supported by the Armed Forces and the Communist Party of Indonesia (Partai Komunis Indonesia, PKI). Guided Democracy was typical of left-wing Bonapartist governments popular across the postcolonial Global South – think about Julius Nyerere’s Ujamaa socialism in Tanzania or Arab socialism in the Middle East, for example. 4 Though illiberal, and sometimes outright authoritarian, it was committed to participatory and economic democracy through active political participation of the lower class, extensive land reform, and control over foreign capital.

But this springtime for democratic class struggle was a nightmare for the budding bourgeois opposition against Guided Democracy. Leading anti-Communist student activists of different persuasions, such as the Catholic conservative Jusuf Wanandi and the liberal-oriented Nono Anwar Makarim, cited increasing state power and leftist political and cultural hegemony as definitive proofs of Sukarno’s “totalitarianism.” 5

For the young economists at that time, including the three future technocrats, it was Guided Democracy’s economic misadventures that triggered them the most. Consider a series of speeches made by Widjojo Nitisastro, then a professor of economics at the School of Economics at the University of Indonesia (UI) between 1963-1966. He championed rational economic development based on modern – that is to say, Western – economics methods. This was a direct refutation of Sukarno’s dismissal of economic sciences as “useless textbook thinking.” Such dismissal, Widjojo argued, had resulted in high inflation and high prices. To bolster the socialist flavor of his argument, he quoted the argument for economic planning by Oskar Lange, the Polish neo-Marxist economist. In a key speech delivered in early January 1966 in front of the anti-Sukarno student activists and UI professors, Widjojo criticized the government’s economic and financial policies.

A section of his speech is worth quoting at length: “When the government urges the people to make sacrifices following the raising of taxes, levies, prices, tariffs and other fees in order to boost its earnings, it is only natural for the people to see it as a moral duty for the government to set concrete examples by effectively slashing its spending first. What the government has done is exactly the opposite. It had raised prices and tariffs enormously, even before it attempted to prove that it could tone down its spending first.” 6 Citing the American Marxist economist Paul Baran’s essay on the social role of engaged intellectuals, Widjojo saw himself and other anti-Sukarno dissidents as social critics who served the people.

Disillusionment with Guided Democracy’s economic policies was also expressed by Emil Salim and Ali Wardhana, two other prominent members of the economists’ guild. Salim, the only living member among the three, is an eclectic economist who learned from diverse intellectual traditions, such as cooperative society, non-Communist socialism, and market economics. Upon his return to Indonesia after finishing his PhD at Berkeley, Salim was appalled by Sukarno’s antagonistic stance against mainstream economics. He complained, “I did not recognise my own country.” 7 A similar concern about inflation was also conveyed by Ali. In a research paper aptly titled “Inflation and Structural Tensions” (Inflasi dan Ketegangan Strukturil), Ali too advocated a policy to combat inflation hemorrhaging the Indonesian economy. 8

Thus, when a golden opportunity presented itself, the technocrats soon seized it. In the aftermath of a failed move to neutralize the anti-Communist High Command of the Army by left-leaning army officers, the Army and the anti-Sukarno coalition of students, activists, and intellectuals launched a counterrevolution to unseat Sukarno, obliterate the communists and their sympathizers, and establish the New Order government. After winning a major political battle against Sukarno’s statism, the technocrats soon implemented capitalist reforms under their aegis.

The revolutionary, eclectic origins of the technocrats’ conservative vision

In contrast to postwar Western conservatives, who were mostly influenced by neoliberal theorists and the horrors of two World Wars, the Indonesian accidental conservatives – the technocrats – had a very different starting point in terms of their political experience and ideological inspirations. To better understand their consequential ideas and actions, we need to look at their intellectual and social history.

First, they were all committed to anti-colonialism. Born in a middle-class family, Widjojo participated in the National Revolution (1945-1949) by joining a student militia and fighting battles against the invading Dutch colonial forces. So did Emil Salim, who was once even captured by the Dutch troops. Meanwhile, Ali Wardhana, whose uncle was the nationalist leader Ali Sastroamidjojo, worked part-time as a clerk at a travel agency to support himself while studying economics at UI. In one way or another, they all come from a petty-bourgeois or proto-bourgeois background, and each of their families participated in the National Revolution.

Second, unlike their more doctrinaire Western counterparts, they were more eclectic and pragmatic. During their undergraduate days at UI, they retained a distrust towards Dutch-style colonial capitalism. However, they found Third World philosophical critiques of colonial capitalism too jargonistic and lacking analytical sophistication. This theoretical cul-de-sac attracted them to modern (capitalist) economic methods taught in the United States.

Their American training at Berkeley taught them the necessary econometric methods to substantiate their prior economic beliefs. But this did not necessarily make them zealot believers in unfettered capitalism. Their conviction was emboldened by their military combat experience and political participation in the early years of the newly-independent Indonesian republic. Philosophically, they were attracted by a range of diverse ideas, including non-Communist socialism, Keynesianism, state-led developmentalism, and modern econometrics. Salim, for instance, focused on Egyptian economic development and institutions under Gamal Abdel Nasser. Indonesia was developing a socialist economy, and he believed that, therefore, the country needed to learn from other Third World states experimenting with a socialist economic model beyond Western capitalism and Soviet socialism. Widjojo, who was already considered to be more pro-market compared to his peers, was a Keynesian, something that would make him a heretic in the eyes of Western fanboys of Hayek, Keynes, or Buchanan. More practically, Ali Wardhana specialized in monetary policy in Indonesia, which was the subject of his PhD dissertation and a timely topic in the context of hyperinflation under Sukarno’s government.

What makes them conservative then? Here, it is important to identify the commonalities and parallels between Western conservatives and Indonesian technocrats. The technocrats’ radical economic vision, at its core, is conservative for the following reasons. First, their politics is a politics of fear by another means. Though their main concern was Sukarno’s economic mismanagement, they also shared the fear of – and anger at – the perceived “ideological” mobilization of Guided Democracy and its statism. This was a major concern of anti-Sukarno student intellectuals such as Wanandi and Makarim and conservative thinkers such as General Ali Moertopo. 9

Secondly, they viewed economics not as bourgeois or imperialist “useless thinking,” but rather as a modern and rigorous body of knowledge that could provide “rational,” scientific solutions for Indonesia’s excessive statism, social and political polarization, and ballooning inflation. This emphasis on rationality was a major rhetorical device and ideological weapon used by the bourgeois opposition against Sukarno and the communists. Therefore, for the technocrats, pro-market economics of various traditions became a tool to exorcise the specter of inflationary, anti-growth statism. Recall Widjojo’s 1966 speech. His critical indignation at Guided Democracy’s hyperinflation and excessive spending is a familiar chorus for anti-government conservatives, neoliberals, and libertarians.

Third, as ministers of the New Order government, these economists saw themselves as fine gentlemen entrusted with the noblesse oblige task of applying the economic scientific methods to solve Indonesia’s underdevelopment. It is not a stretch to say that this sensibility, seeing themselves as warriors in the battlefield of politics and ideas, is both conservative and radical at the same time. In executing the task, they became the midwives of capitalist restoration and consolidation in Indonesia after a brief flirtation with Marxist-inspired socialism.

Finally, the technocrats successfully shifted economic and political languages of their time from left-wing discourses on radical collectivities and class struggle into practical policy concerns with an emphasis on individual rights (in the market) and responsibilities (in development) in an ordered society. This shift was institutionalized by their educational efforts at the UI School of Economics, where they trained generations of professional economists for decades. One can call this a conservative appropriation of postcolonial socialism and Keynesianism. 10

The radical element in the technocrats’ approach was their commitment to rejuvenate society through a process of total reset. Their experience in the anti-colonial struggle emboldened their faith in their craft, vocation, and politics. Moreover, their continued adherence to the (vague notion of) Indonesian communitarian traditions and the Keynesian and quasi-socialist undertones of their economic thinking allowed them to push forward their visions during critical political junctures.

The accidental conservatives in power

When the New Order won, ousted Sukarno, and annihilated the communists, the economists were able to control the levers of power in economic policy. In the name of saving the Indonesian economy from the brink of bankruptcy, they dismantled existing socialist-populist experiments, including extensive land reform and democratization campaign in rural areas. Instead, they provided analytical and practical justifications for capitalist reforms. This included balancing the budget, rolling back the role of the state, providing space for the market and private sector, integrating Indonesia back into the global market economy, and providing subsidies as concessions for the lower-class. But make no mistake: these policies, at least up until the wave of economic liberalization in the 1980s, were not a carbon copy of Western conservatism. The technocrats retained some elements of communitarian concerns in their policies, such as addressing mass poverty and providing basic education for citizens. Their economic policies became something like the New Order consensus shared by the diverse anti-Sukarno coalition, the growing capitalist class, and the broader public.

As a result, Indonesia entered a period of rapid economic growth and stable development. However, this radical conservative experiment relied on an authoritarian mode of bourgeois politics free from the disturbance of the masses in the service of capitalist consolidation. Consequently, this experiment inadvertently became a defense for stable, boring politics. Elections and democratic procedures were a predictable façade for business-as-usual for Suharto, the New Order dictator, and his supporters and cronies. Eventually, the increasingly corrupt and repressive rule of Suharto in the later years of the New Order regime became too much to handle and therefore unacceptable, even for the technocrats. Starting from the late 1980s, critical activists and intellectuals openly challenged the New Order developmental mantra, including its economic model. The technocrats lost the very constituency that propelled them to power in the first place.

Concluding remarks

Unearthing the conservative dimensions of the technocrats’ vision for modernizing Indonesia opens up new readings of economic thought in Asia and the Global South. Conventional interpretations of the technocrats typically emphasize two aspects: (1) their mastery of modern economics and appropriate policy measures, a point raised by economists; or (2) their pragmatism, as exemplified in the political scientist Rizal Mallarangeng’s study. 11 Delving deeper into the biographies of the technocrats and situating their ideas and actions within Indonesia’s developmental trajectory and global intellectual history help us to appreciate the value of their analytical eclecticism and its contribution to conservative economic thoughts. The continuing popularity of their ideas in policy circles and public discourses is a testament of their lasting legacy.

The Indonesian technocrats are not alone in this regard. Japanese thinkers, though inspired by neoliberal doyens, concocted their own theory of cultural neoliberalism which centers the nation, as opposed to the state, as a reservoir of pro-market culture. 12 Singaporean state builders succesfully created their own amalgamation of conservative communitarianism, combining illiberal politics, market capitalism, mass public housing, labor market flexibility, interracial harmony, and electoralism, all inspired by survivalist ethos and elements of Western social democracy. 13 In faraway Ghana, economists, sociologists, and politicians embraced the market as a tool for national liberation in the 1970s and 1980s, essentially creating an anti-colonial brand of capitalism. 14

The accidentally conservative nature of the Indonesian technocrats’ vision and conviction enabled their nation to move forward. This accelerated pathway to capitalist development, however, was achieved in a bloody manner and with a heavy price. In the end, their ambition was eclipsed by growing discontent with the New Order and a more critical assessment of the regime’s failings. 15

Iqra Anugrah is a Research Fellow at the International Institute for Asian Studies (IIAS), Leiden University and a Research Associate at the Institute for Economic and Social Research, Education, and Information (LP3ES). In October 2024, he will serve as a Research Fellow at Central European University Democracy Institute (CEU DI). Email: officialiqraanugrah@gmail.com