River Cities Network (RCN): Engaging with Waterways in the Anthropocene

A transdisciplinary and global network to promote ecologically and socially inclusive revitalization of rivers and waterways and the landscapes, cities and neighborhoods that co-exist with them.

Strengthening the river-city nexus

The River Cities Network (RCN) is a multi-sited global initiative to pursue action research on the interrelationship between cities and their rivers and waterways. In the RCN context, we are interested in free-flowing or engineered rivers, creeks, canals and/or networks of these as part of a river system in urban or peri-urban areas. The “river-city nexus” is our shorthand for the mutual relationship between these water bodies, their ecosystems, and the human settlements that surround them.

The river-city nexus provides a lens through which to critically analyze relationships between human settlements and rivers and waterways over time, as well as a platform to engage in collective action to revitalize local river/waterway ecosystems and to improve their relationship with adjacent communities.

The outcomes of this initiative will be practical in nature—culminating in local urban revitalization schemes—as well as knowledge-based, leading to new insights about how to integrate “transformational resilience”, including notions of justice for nature and humans, and biodiversity restoration in theory and in university/school curricula.

The river-city nexus is about “disruption”, and about recovery and resilience. “Disruption” refers to human interventions to exploit and alter the natural course of rivers and waterways—and vice versa, the impacts of these (often engineered) water bodies on human, animal, and plant life in urban areas. This cycle is frequently exacerbated by natural and climate change factors.

The RCN is a network comprised of project teams from all over the world, each of which analyses a local river-city case study. A river or waterway system is the entry point in each case, with a focus on the interaction between these water bodies and adjacent communities. Each team comprises a mix of local scholars from different disciplines, scientists, and activists, whose mission is to engage with a broad range of stakeholders in seeking to revitalize the stretches of river, creeks, or canals that they select as case studies. At the same time, each team will also engage with disruption issues identified by the other river city teams, in comparative perspective, thus helping to build a network. The network seeks to be truly global in nature, with learning and innovation between and within the global North and global South.

Rivers as mirrors of their societies, and the Anthropocene

Rivers are found all over the world. According to International Rivers they function like arteries in the body, “providing the world’s ecosystems with critical freshwater resources that sustain a higher biodiversity per square mile than almost any other ecosystem”. At the same time, rivers have played a universal role in facilitating the rise of human settlements. As these settlements have grown, humans have tried to engineer rivers and create waterways to their advantage. The way they have attempted to do this reflects their socio-economic and cultural needs and the local power structures over time. Rivers and waterways thus mirror the societies that have attempted to shape them and the time periods when these interactions have taken place.

Today, the river-city nexus in a multitude of places is at a breaking point, reflecting many of the challenges presented by the Anthropocene. The fragmentation, diversion, mining and pollution of many rivers and waterways endangers the food security, livelihoods, and cultural traditions of millions of people. The effects of climate change exacerbate river degradation, in the form of flooding, drought, and unpredictable water levels and quality, made worse by man-made interventions. This trend is especially pronounced in urbanized areas, where the health of river ecosystems competes for attention with many other policy priorities.

Twin objectives of RCN: strengthening justice and biodiversity

The RCN is motivated by three broad research questions, which are the basis for the network’s components, and which link the different case studies: 1) What does the river-city nexus look like? 2) What have disruptions revealed over time? and 3) In what ways can rivers and waterways better sustain productive urban life, and vice versa?

Key indicators of a productive life for RCN are improved water quality and increased biodiversity, and socially, culturally, and economically vital and just communities. This corresponds to the two objectives of the River Cities Network, the pursuit of justice and biodiversity, which are critical to a restoration of the relationship between rivers/waterways and cities.

Transformational resilience and justice

Transformational resilience refers to the need for longer-term, structural, and multi-faceted measures to address disruption in the life of the river and the communities that depend on the river. The term acknowledges the need for a normative approach, which recognizes the socio-economic, cultural, institutional, and political dimensions of resilience 1 —not just the technical dimensions that are often the sole criteria in resilience measures of so many planners. The normative lens implies the need for a more explicit focus on “justice”, in the sense of correcting conditions that are unfair, for (human) communities and (natural and human) ecosystems that have been “wronged” in some way. RCN recognizes the highly subjective nature of the concept of justice, and it does not seek to impose a uniform definition but to embrace robust discussions on what is just/fair and unjust/unfair, and for whom and what, in each local (case study) context. Research on “transformational resilience” is still at an early stage, as is the application of this budding concept to practice 2 . Each river-city case study in the network will contribute its own context-specific insights. Exchanges and peer-to-peer support among the participating project teams will help to develop learning and pedagogy around this concept, for the benefit of the network partners as well as scholars and practitioners more broadly.

Biodiversity

The 1992 Convention on Biological Diversity defines biodiversity as the “variability among living organisms from all sources, inter alia, terrestrial, marine, and other aquatic ecosystems and the ecological complexes of which they are part”. This view of biodiversity is narrower than that held by many indigenous communities around the world, whose view of biodiversity includes culture and social diversity of a people, “tied to both nature and humans”, as well as territory and living space 3 . For a network interested in the nexus between river (nature) and city (humans), it is intriguing to ask whether one of the contributions of RCN can be to broaden the focus on “biodiversity” to also include the cultural diversity of humans.

Linking justice and biodiversity

Despite the recognition of the importance of both objectives, work on transformational resilience and biodiversity restoration typically proceeds in separate “silos”, both in theory (in higher education curricula and research groups) and in practice (in government departments and advocacy by civil society). The RCN network seeks to create a precedent for a more holistic approach, by integrating both pillars (biodiversity and transformational resilience/justice) in its approach, by:

- Approaching river disruption issues in each case study project from the perspective both of nature (biodiversity) as well as humans (justice).

- Encouraging RCN project teams to have a mixed composition, with members from the natural sciences and social sciences and humanities, and to encourage a transdisciplinary approach.

- Contributing to theory, by building on the insight—propagated by Steven Brechin (2012)—that nature protection is as much a process of politics, of human organization, than of ecology, and that "although ecological perspectives are vital, nature protection is a complex social enterprise” 4 . This insight leads to the important conclusion that both sets of knowledge and action are necessary to realize nature protection (in the RCN case, river revitalization).

- Adopting methods and tools from both the biosciences and the social sciences and humanities, to realize the project teams’ river revitalization objectives.

Network components

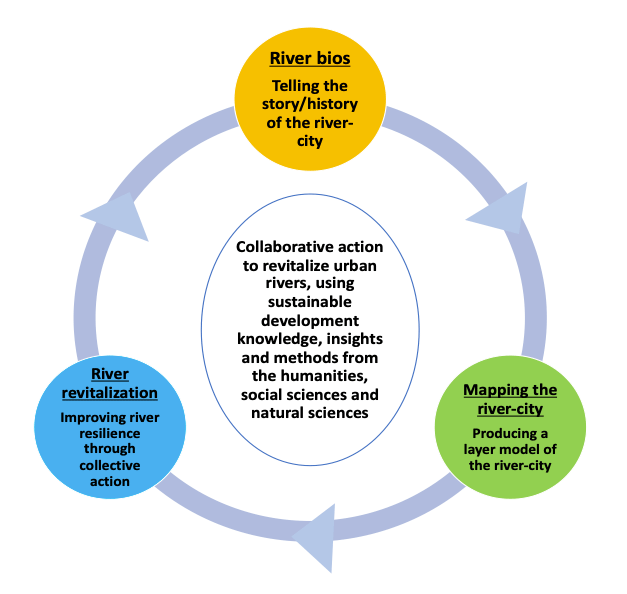

RCN adopts a trans-disciplinary approach, bringing together knowledge of river-city ecosystems from the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences around three main project components, which strengthen each other. The three components correspond roughly to a focus on the river-city’s “past”, “present” and “future”. These components will be broadly sequential (starting with river bios) but there will also be overlap so that findings from each component can feed into each other.

The river bios component dives into the history of the river city. This component aims to “tell the story of the river city”, through a mix of methods including archival but also ethnographic research, including interviews and focus group discussions with experts and non-experts, such as riverine communities and other groups (farmers, fishers, enterprises along the river, and others) who depend on the river.

In the mapping component the project teams collect and map data to understand the current state of the river-city relationships in each case study city. Data may come from official sources as well as from archives and unofficial sources, such as ethnographic data collected during the river bios component from residents and other local stakeholders. The maps serve as an outcome in their own right, but their value is also that they constitute a basis for a participatory mapping process and as a basis for the river revitalization efforts in the next component.

The final component, river-city revitalization, is based on collective action. In this component, each case study team will design and coordinate a river revitalization strategy aimed at restoring new life to the river and the river-city in a holistic fashion, i.e., in terms of river environment and ecology, linked to transformational resilience/justice and biodiversity goals it has set for itself. Each team will do this by building a coalition of local stakeholders. Outputs for pedagogy and awareness-raising may also be the focus of the strategy. Inputs for the river-city revitalization strategy are the data and maps collected and developed in the river bios and mapping components. The teams may build on existing river-based initiatives, where available, and collaborate with local partners who are already engaged in these or related efforts.